Imran Khan and his PTI must be given a fair chance to prove their political prowess. The arising political equation has structural disconnects and these will emerge. But that is for the future

The nation has just accomplished the once distant dream of two consecutive and complete tenures of elected governments and the third electoral exercise in succession. Since 2008, the voters have opted for three different political parties at the national level. Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) will be taking charge of the national affairs in the capital for the first time, though its chief Imran Khan has been one of the most enduring faces on the national horizon for more than three decades now.

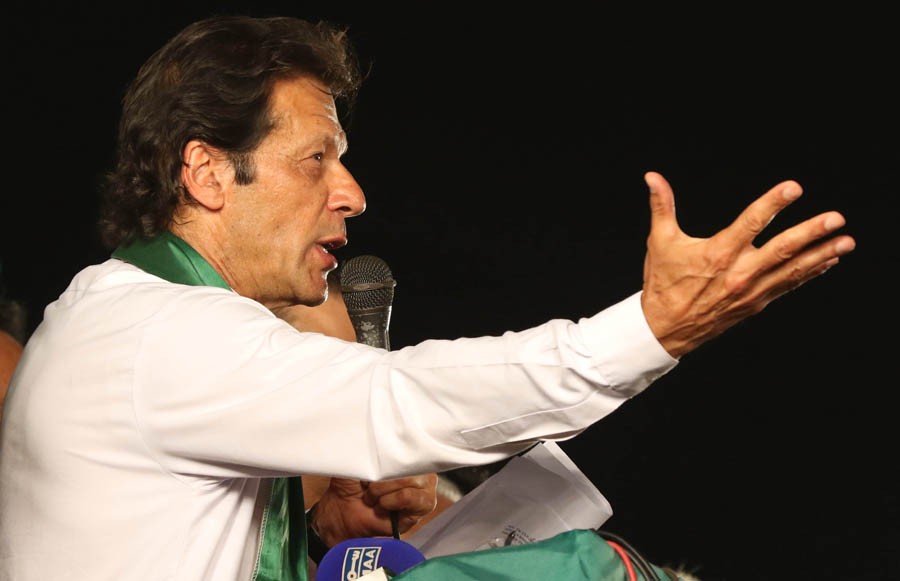

Imran Khan vouches for a new Pakistan. Apparently, his vision for the change revolves largely around administrative efficiency and financial transparency. Corruption is the buzzword that has rallied a whole generation in a bulging population with a median age of only 22.6 years. The buoyant faces of this young multitude hide the bitter realities of dysfunctional literacy, poor political education, an indoctrinated world view, and dire economic constraints that seriously challenge the onward journey of their country. Mesmerised by the charisma of a flushed leader, his firebrand (though often over-simplistic) oratory and the reputation of a never-say-die approach on the cricket grounds around the world, the young men and women have come to invest their dreams in Imran Khan.

The electoral exercise in the last week of July has left a lot to be desired; though mainstream political parties appear to, at least for the moment, accept engagement with the parliamentary system in the name of continuity of the constitutional process. Therefore, it is time to analyse the dynamics of Imran Khan’s emergence as a formidable political force and its long-term prospects.

There are four factors that need to be examined separately: Imran Khan (the person), Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (the political party), rival political forces (broader political spectrum), and the flux of emerging socio-economic fabric that has invested the political mandate in Khan and his party. Last but certainly not the least, is a fifth element, namely, the entrenched power equation, ridden with bouts of estrangement between civil and military leadership of the country.

Imran Khan, the cricketer turned politician, is a maverick character, strung through binary streaks of a tribal, patriarchal, and hierarchical society of north-western Pakistan and the British aristocratic circle of 1970s. Brimming with self-confidence, an ingrained sense of destiny, an undying urge to lead from the front, an extrovert used to adulation of the faceless mob, a self-engrossment bordering on arrogance, and a thinly-disguised romantic character, Khan is a born leader. He is not known for profundity, critical faculty, or strategic vision. He loves to ride the spur-of-the-moment tactical ingenuity.

While comfortable with the paraphernalia of the modern world, he has a mystical side that adds a subliminal angle to a pile of cross-purposed traits. He prefers to keep his political message simple and repeat it to the tone of a mantra. He loves to denounce whosoever or whatsoever counters his ambition. It allows him to portray himself as a divine-driven phenomenon above the ordinary mortal beings. Khan has the ability to command a blind followership which can ignore his personal contradictions and political somersaults.

PTI, the political party run by Imran Khan like a personal fiefdom, is undoubtedly the product of a mindset embedded in the post-Afghan war (1979-1989) of Pakistan’s militaristic elite. Basking in the asymmetrical patronage of the Zia dictatorship as a sports hero, Khan embraced the pro-jihad ambiance of the comfy lifestyle of the retired military generals, recounting their military exploits against the Soviet Union and creating the mirage of a revolution that would rid the country of the corrupt, inefficient and uncouth politicians.

1990s was the decade of proxy governance in Pakistan, where the shots were called by the invisible masters while the brunt of the failures was assigned to the political masquerade. Imran Khan had two points to sell: his incredible leadership in the 1992 Cricket World Cup, and a charity cancer hospital that he built, in commemoration of his late mother; hardly enough stock to run a successful political initiative. His closeness to the powerful military circles and his propensity for clandestine escapades were common knowledge but he had perhaps the most recognised face in the country.

His every move brought grist to the mill of media. He was able to rally a significant political team, mostly drawn from the urban, educated, upper middle classes of the country. An amalgam of revolutionary zeal, express hostility towards Western democracy, a promise to fulfill the socio-economic dreams of a largely disempowered youth, PTI was a little more than a country club ensemble.

Khan’s political party participated in the 1997 general election, and his party was comprehensively beaten on each and every seat it contested. However, Imran Khan continued to occupy a piece of political spectrum. During the catastrophic tiff between the elected government and military leadership, in the wake of the Kargil episode, Khan stood by the shady politics of demolition. The emergence of military dictator Pervez Musharraf propelled Khan and his party as a serious prospect because of his support to the unconstitutional regime.

However, his party could win only one seat in the orchestrated electioneering exercise of 2002. With one seat in a house of 342 members, Imran Khan was the star of the media. His philanthropy was touted as a miracle out of this world. He was the clean man, averse to corrupt ways of the traditional political forces, and he was a natural leader to a nation of bulging youth.

The emergence of private television channels helped Khan and his party immensely. Every evening, his face reached almost every household like a ritual. Then came May 2011, and with it the Osama Bin Ladin operation in Abbottabad, which was a huge embarrassment for those responsible for national security.

By July 2011, Imran Khan and his party saw a reinvigorating resurrection. A huge political rally on October 30, 2011, in the historic Lahore Park, worked like the Munich Putsch of 1922. Within weeks, seasoned politicians and wealthy characters were flocking to his party like they had seen beyond the mountain. Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), a formidable political force for half a century, disappeared into in the thin air. And, Imran Khan was the next big thing to topple the Muslim League of Mian Nawaz Sharif (PML-N) that had ruled the country as well as the biggest province of Punjab for two decades. Khan failed to win the election in May 2013 but snatched a significant chunk of parliamentary representation. His party even formed a government in the volatile province of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa (KP). The next five years were an exercise in political expediency. The powerful deep state was unhappy with the actions as well as ambitions of the democratic political forces. Imran Khan was the rabble rouser on the road, while an intricate nexus was created whereby judiciary had to accomplish what direct military intervention would have done in the past.

Apart from the political rigmarole, huge changes were taking place in the socio-economic fabric of the nation. Once predominantly rural, Pakistan was fast turning into an urban country. The official economic statistics belied the fact that large segments of young men and women were either unemployed or under-employed. Easy access to an emerging media of information had created unprecedented awareness about the world in the 21st century.

Khan succeeded in convincing the people that they owed their poverty, poor education and health facilities, and shabby civic amenities to the shenanigans of the traditional political forces. He drove home the message that his personal honesty and charismatic faculties could take Pakistan into the 21st century. He could negotiate with the world at large as well as bring stability at home. His message was simple: "People of Pakistan, I have arrived. Rally around me." And rally around, they did.

There was a protracted campaign of media trial, malicious propaganda and fabricated scandals. There were salvos of not-so-subtle messages that the men in uniform had an unfavourable view of the elected leadership. An almost crusade-like judicial process was unleashed in the name of accountability which could at best be labelled as tainted. Large chunks of political power were arrogated without much trouble as one political entity was pitted against the other.

In this mayhem, there was one political leader and one political party that could work without any fear of distraction: Khan and his PTI. Hordes of "electable political figures" joined PTI in a ritualistic way that almost looked like a farce. Gone were tall claims of clean and principled politics. Imran Khan told his followers that they needed candidates who knew the "science of winning elections." The mere prospect of Imran Khan, the saviour, ensconced on the prime ministerial pedestal, convinced his followers that they needed power before they could change the country. They conveniently ignored that the promised change was supposed to uproot the very political forces that Khan was now embracing to bring about the change.

The significant segment of populace who still harbours doubts and apprehensions about the political viability of Khan’s model have to accept a basic reality: such are the ways of politics, and this is how democracy works. Khan has successfully brought together huge sections of society that had become depoliticised through decades of decadent politics. There is no denying that nearly 17 million voters have opted for his political party in recent general elections. His party is going to form government at the centre as well as at least three provinces. Khan and his party must be given a fair chance to prove their political narrative. The emerging political equation definitely has some structural disconnects and these will emerge sooner. But that is for the future.

Sitting in August 2018, the democrats of Pakistan must respect the mandate invested in Imran Khan and his political party by millions of voters. One must not forget that some pillars of the entrenched political clout have been demolished. A significant number of so-called ‘electables’ has failed to reach the parliament despite their gimmicks. For the first time in the history of this country, we are entering a third consecutive elected government without an unconstitutional interregnum. This election has clearly brought to the fore some fundamental contradictions of Pakistan’s political paradigm. The proper way to negotiate this challenge is to adhere to the constitutional scheme and trust the political acumen of the voters.

Let us welcome the era of Imran Khan and his political potion with the hope that at least parts of the problems will be seriously addressed. Further, Khan by virtue of being the leader of the elected parliament will have to change the tack. For now, he is the face of democracy. We should never forget that democracy, with all its weaknesses and pitfalls, has no alternative. We may trip, falter, or stumble along the democratic path, but the only remedy for such contingency is more democracy.