A section of India is uneasy with Imran Khan’s rise to power because it knows from experience the perils of a right-wing player

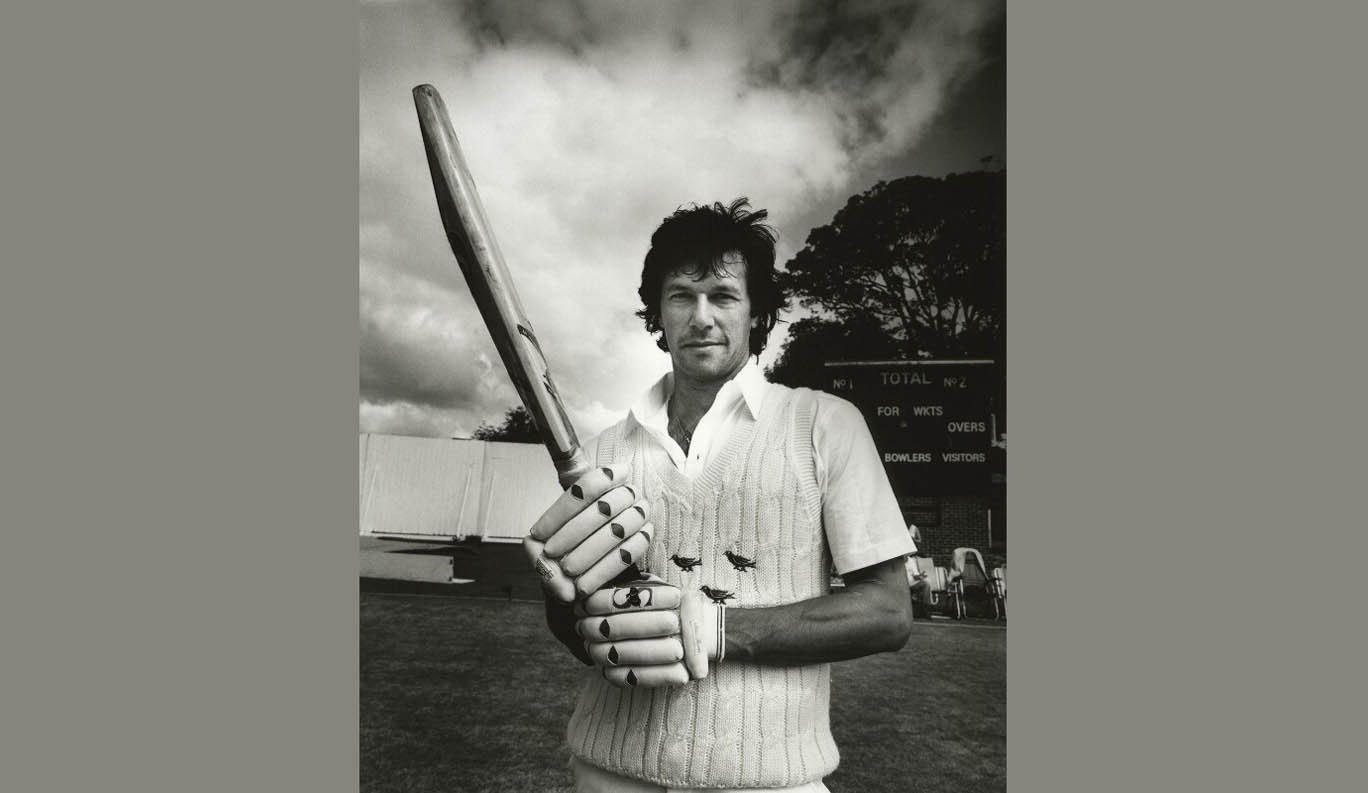

It is that moment in India when people in their mid-40s are busy reminiscing their earliest or most enduring memories of Imran Khan.

Mukul Kesavan, in a recent piece published in The Telegraph, recalls Khan’s feat in the 1976 series to Australia, where he played a crucial role in equalising it.

My most abiding memory of Khan, though, is from 1983 when the Indians visiting Pakistan were thoroughly humiliated by his team, and the lone man standing most often was Sunil Gavaskar. We took solace in those small face savers. That was also the year when India won the World Cup, which left another legacy for Khan to pursue.

I vividly remember discovering in my school library a long photo essay on Imran Khan amidst his traditional Pashtun tribesmen, posing with their assault rifles (fake or otherwise), published in the National Geographic Magazine in the mid-1980s. The photographs of this handsome man published on glossy pages with a certain aesthetic left a lasting memory of someone who didn’t belong to this world -- in a world full of mundane people, he came across as someone destined to rule. I guess, one can say that in hindsight.

I also recall the moment when he lifted the World Cup trophy in 1992. It sounded fairly natural to us university students or early career professionals to see him lead Pakistan to victory. So, his announcement to enter politics sounded like the next natural course to take for a man with such charisma and sense of entitlement. All we had to do was wait till it happened.

And now that it has happened, the Indians are marvelling at this new chapter in Khan’s life. This time he is neither viewed as a cricket celebrity nor a bête noire but a leader poised to impact the relations between India and Pakistan and the lives of people across the border in myriad ways. The old unease is intertwining with his cricketing legacy, and is giving him a new lease of life as an upcoming political leader. While his public position on Taliban, Kashmir and his supposed proximity with the army is viewed with scepticism, experts look at his rise as the next chapter in the ‘Great Game’ played out in Afghanistan.

Will this prove to be the cricketing turf where Khan will bowl India out? An important sphere of hegemonic influence? How will he play China against India when the Indians are staring at the Chinese in Doklam and elsewhere? Will he be the right guy to trump Trump in times when the US is hostile to Pakistan? Predictably, the mainstream Indian media has gone all out in weaving suspense stories around Imran Khan inspired by Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

In his victory speech on July 26, he stated how he was portrayed as a Bollywood villain in the Indian media. At the same time, his offering of peace to the Indian people on the grounds that India knows him as much as he knows India has helped dispel the impression of him being ‘Taliban Khan’.

It needs to be underlined here that it isn’t India alone which holds apprehensions regarding Khan’s ‘ascension to the throne’ (this phrase sounds most appropriate in his case). Rather, the western liberal press, led by the likes of The Economist, have been writing about his conformist stances and its implications for Pakistan and its neighbours. Notwithstanding who is invited to his swearing-in ceremony from India, people are waiting eagerly to see how his early days as the prime minister pan out.

What really is the Imran Khan phenomenon? A cricketing super star now a prime minister-elect. A saviour of a semi-literate, quasi-feudal, IMF-dependent economy or a messiah of the right-wing in the times of right-wing politics across the world? Much as we Indians tom-tom about the strength of our democratic institutions and coming of age of capitalism, the rise of a right-wing, self-proclaimed messiah with a promise to liberate a Hindu majority (even though it may not have happened with the help of an aggressive army, but army is certainly being more politicised in India now than ever) certainly doesn’t sound much different from the establishment in Pakistan today.

Is the difference then merely that of Oxbridge upbringing of Imran Khan in a conservative context versus the fabled tea-seller upbringing of Narendra Modi in another conservative context? Or is it a peculiar South Asian phenomenon where whatever route you take, you need to conform to the establishment in order to remain relevant?

This is why at least a section in India is still uneasy about Imran Khan’s rise to power -- because we know from our own experience the perils of a conformist, right-wing politician in our backyard.