I knew nothing about Mumtaz Athar. As a matter of fact I still know very little about him. It was only accidentally that I came across his collection of poetry entitled Mahbas mein Darar (a crack appears in the prison). I picked it up desultorily. So many collections of poetry get published these days that it is getting hard to take any notice of them at all. Not to do so, however, seems deplorable. You may overlook the work of someone promising or of someone who definitely needs to be applauded or encouraged.

Mumtaz Athar’s ghazals struck me as noteworthy in a particular way. Here was poetry politically engaged, not overtly left, but still comfortable, in sporting parlance, in a left out position. I think it is lucky that he did not write during the heyday of the Progressive Movement. As literary movements go the Progressives made important contributions, both in fiction and poetry, forcing many of us to realise that the social and political setup we had condoned, if not espoused, for a long time was unjust and exploitative and did not conform with the swiftly changing circumstances. The movement was like a breath of fresh air in a stalled milieu.

It finally fell apart because of regimented thinking, of showing more loyalty to the dictates of the party than to the writers’ creative selves.

To kowtow to a party’s discipline can be disastrous as far as the freewill of the creative artist is concerned. The party can make demands which will not only be flippant but also at times plainly nonsensical. For example read the following stricture on Anna Akhmatova, a fine poet, imposed by party hacks back in those days when everything was dictated from above in the Soviet Union: "Akhmatova is a typical exponent of empty, frivolous poetry that is alien to our people. Permeated by the scent of pessimism and decay… frozen in the position of bourgeois-aristocratic aestheticism and decadence… not wanting to progress forward with our people, her verses cause damage to the upbringing of our youth and cannot be tolerated in Soviet literature." Nothing new here. Every ideological state sets out to strangulate the arts.

But let us get back to Mumtaz Athar’s ghazals. The political element in them is subtly ensconced in expressions which do justice to ghazal’s perennial insistence -- to say more in less words -- and also to underline, with sadness and resolve, the longing to break out from the straitjacket of conventions, conformities and outdated orthodoxies, to strive for the beginning of a just world order. A yearning for an ideal nowhere to be found but something which good poets and writers have always stood up for.

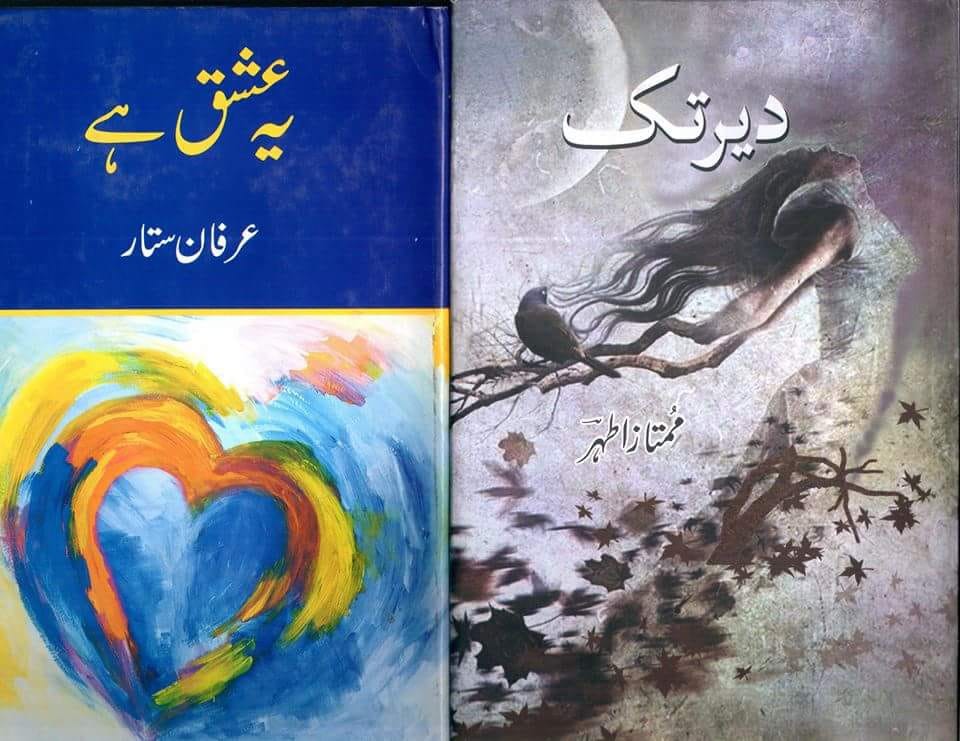

His ghazals eschew rhetoric, possess an unassuming dignity and pleasing consonance. I wonder why he has not been taken more notice of. I have also received a new collection from him called Dair tak (quite a while). It does not look as fresh as Mahbas mein Darar. Perhaps the element of surprise and discovery has been lost. Nevertheless it is a neat collection, readable and undemonstratively contemporary. There is also the realisation, certainly not arrived at by reading the latest scientific thinking, that we live in a participative universe and can’t comprehend it because we are ourselves involved in it. As he says, "I am not the pageant. I am a part of the pageant."

He has also managed to devise a new form named "Sat roopi", poems consisting of seven lines, four long, three short, with the following rhyme scheme: abbc dde. This has potential which has not been fully exploited in the examples included here but nevertheless can be turned to better account with more perseverance.

There are some "Vais" also, a form rhythmically close to song with which he seems particularly at home.

It does seem a pity that I cannot comment on his entire corpus. There are two books by him, one consisting of ghazals and the other of poems, which I have not seen. Such being the case, my comments must be seen as something not wholly apposite.

To turn now to Irfan Sattar’s ghazals found in his book Yeh Ishq Hey (It is passionate love) is to enter a new territory. Both Mumtaz Athar and Irfan Sattar have a penchant for ghazal but at this point the similitude comes to an end.

Irfan is a poet more in the classical mould. All the concerns of the ghazal which are taken for granted are there but somehow a new gloss, a meaningful particularity, more aligned to the here and now, shines forth. The ghazals are mainly about being in a state of love but with a reservation. In short, all the lover’s tribulations, sensations, elations and the permanence and unfulfillment have been splintered by the ravages of an age intolerant of the savoir faire of passionate love.

How to transform such inclement infelicities into verse which can be incisive and personal? It is an enduring problem and becomes more acute because of ghazal’s peculiar thriftiness and prescriptive restrictions. However, Irfan Sattar handles the issues with panache and a slinky irony. The barbed comments are cleverly toned down.

Ahmad Javed, himself a very fine writer of ghazal although rarely acknowledged as such, commenting on Irfan’s achievement, remarks: "I am sometimes amazed that he can transform nearly every feeling, that is to say joy or grief or else, not only contentwise but also endows it with a fresh meaning."

There is another aspect of Irfan’s ghazals which has not been remarked upon. How close the lines are to prose and how the poet by placing his words adroitly elevates them to a position which stands in defiance to prosaic statements. To do so requires considerable skill. This interplay of the plain and the complex, this slight shift of the ground, stabilise his ghazals with an uncommon equanimity.

His predilection for choosing longs metres should also be noted. In fact, in one ghazal the lines are so long that a very fine print was needed to accommodate them on the page. While such oddities are not objectionable, his overuse of internal rhyme is off-putting.

Dair tak has been published by Zouraiz Academy, Multan and Yeh Ishq Hey by Book Home, Lahore.