With his photo-poetic perception, Sharjeel Anzar is not just reframing time but also redeeming it of its nostalgic burden

In 2008, Chronicle Books published a retrospective on Mexico’s supreme art photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo. This compilation featured images which reflected "poetry of Bravo’s photojournalism" and his "fascination with dreams and death." The 336-page book was titled ‘Manuel Alvarez Bravo: Photopoetry.’

It wasn’t a new term for photography. There is something very similar between poetry and photography, some common ground where verse and visual arts connect to explain each other, for which a term ‘ekphrasis’ is conveniently used. Keat’s ‘Ode to a Grecian Urn’ is a fine example.

Quite often, poets and photographers look at life from the same viewpoint. Poets are spurred by sheer inspiration, perhaps through spontaneous feelings recollected in tranquility. Sometimes from a personal perspective, or by images which subsequently become dramatic settings for their poems. Photographers are mad Romeos capturing visual memoirs from the rubble of everyday reality by chasing ephemeral light and fleeting time. Poets and photographers translate ordinary human experience into extraordinary emotion.

"All is commonplace sentiment

All is commonplace word

By chance they meet a poet

They are transformed into many new poems."

(‘Dreams and Poetry’ -- Hu Shih)

Poets or photographers, both turn ideas into images, a process which American poet Gary Snyder compares to "roaming about in the landscape of your mind." It is a practice that seeks life in dying moments. While re-enacting reminiscences, poets and photographers become archaeologists of nostalgia. They document personal and collective catastrophe caused by the lapse of time. Susan Sontag calls this "memento mori" (remembrance of death); "all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt." Regardless of how a verse or image comes into existence, only poets and photographers portray humanity as greater than its tragedy.

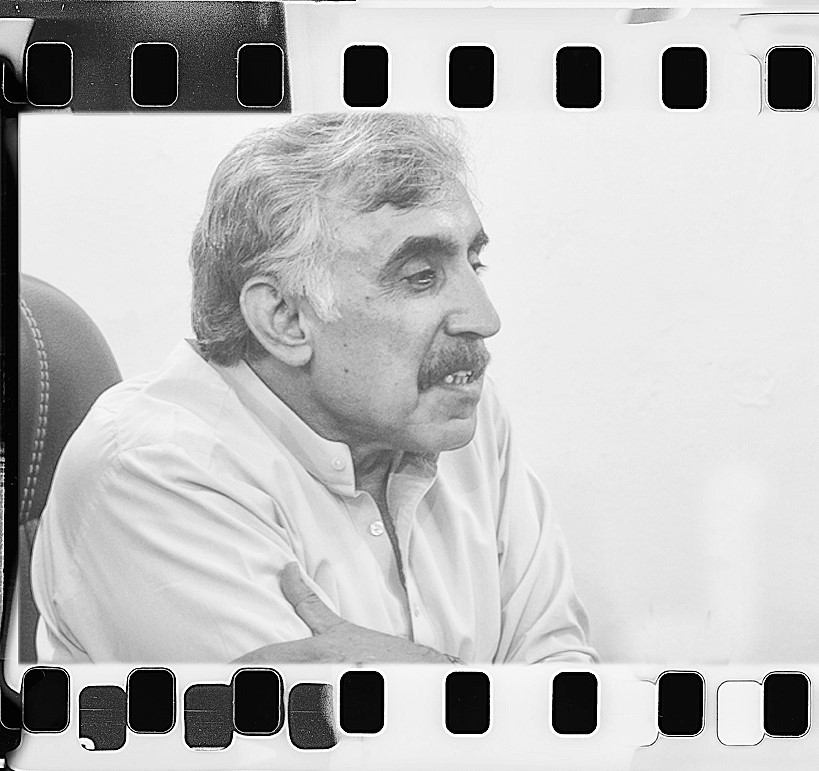

So what went wrong with Sharjeel Anzar, a poet in the 1980s, that after a prolonged silence spanning two decades he resurrected himself as a photographer in the next century? In his own words, first a "victim of maturity at a mellow age despite his comfortable upbringing," later he became a "conformist" by joining the civil service in 1996. "Creativity cannot co-exist with conformity. The moment I joined office, I lost touch with the immediate experience of life," he says.

It was not just a bureaucratic position that arrested the flight of his poesy but the tyrannical frigidity of Zia’s military dictatorship that snubbed the cultural and intellectual milieu of his era. His early verse carries traces of this agonised realisation with powerful forewarning:

He documented this existential apprehension of living in a wasteland and the affliction of intellectual barrenness in photographic references:

Pakistani photographers from 1960s to 1990s working in various photographic genres excelled in international salons. Nisar A Mirza, M Hanif Malik, Aftab Ahmad, M R Owaisi, Syed Javaid Kazi, Shaikh M Amin, Mushtaq Cheema, Sami Ur Rahman, Nayyer Reza, Azam Adnan and Saleem Khawar made regular appearances in Photographic Society of America (PSA), Fédération Internationale de l’Art Photographique (FIAP), and several other prominent forums. Many made it to top 25 exhibitors’ list and won prestigious awards. Most of them called themselves "pictorialists." They built a visual wealth of imagery photographed in controlled environments and processed with laborious darkroom techniques. Shahid Zaidi, Mian A Majid, Zafar Ahmed and their creed dominated in studio portraiture with occasional landscape and cultural photographs. Faustin Elmer Chaudhry (F E Chaudhry) and Azhar Jafri also established high ideals of photojournalism.

The turn of the century not only replaced analogue autofocus camera technology with digital sensor and daylight darkroom but also set the perfect scene for Sharjeel Anzar to give vent to his dormant poetic liaisons through photography. His frozen memory began to melt into a series of ‘film negatives’ he shot in India, and he began to ‘digitise’ them with a newfound fervor in 2004. While his contemporaries continued to exalt in pictorial photography, landscape and documentary, Anzar primarily focused on what I’d call "memory image," i.e. he attempted to recreate pictures of euphoric Punjabi lifescape, which despite sightlessness imposed by a despotic military regime, never ceased to exist in his remembrance.

His photographs of a young girl standing in the doorway of a painted mud house, kids playing "kokla chhapaki," "skipping rope" and "flying kites" in mustard fields, and women buying bangles in the narrow streets of Rawalpindi strengthen Anzar’s point of view that these past times were not only confined to rural life but were a strong element of daily life in urban centres.

"In my youth we had longer voids of time and less technology. People took afternoon naps as a religious obligation," he says, "Urban kids had televisions and cars at home but they also played hide and seek, and girls tied swings on high branches to welcome the spring. Cinemas, theatres, tea houses, and social clubs were crammed with enthusiastic audiences. Society was tolerant but those times had their peculiar aggression. We gained political consciousness much earlier. We read great books and engaged in haughty debates. But gradually loss of ideology sedated all arts," he laments.

Anzar’s generation is a witness to a lost world. The dreary emptiness which dragged every living soul into despair in the late 1970s left indelible scars on his sensibility.

Anzar’s goal is to break the static impression of a technically perfect picture. He is a firm believer in Ansel Adam’s famous saying, "You don’t take a photograph; you make it." The margin of ‘making’ leaves him with endless options for carefully planned images. This also involves extensive travel in search of suitable locations and real-life characters. Once everything is in place, he is all set to translate his dreams into memorable photographs.

Roger Shattuck in his article ‘Proust’s Binoculars’ claims, "Proust wrote out of an inner vision trained on time." For Anzar, that vision of time is "past." "Entire source of my art is rooted in my past," he says.

Contrary to present-day Pakistani photographers, Anzar’s lifescapes are neither pulsating images of festivity and pastoral rituals of a vanishing tradition, nor a requiem for a dream. These are re-enactments of a socio-cultural ambience that once defined the utopia he used to live in. He does not use memory image as a metaphor of ruin, but as a treasured experience he wants to share with the present generation. Anzar, with his photo-poetic perception is not just reframing time, but also redeeming it of its nostalgic burden.