Can it be said that the rise of Urdu poetry is literature characterised by an age in turmoil?

The relationship between objective reality and artistic output has been a tricky one. Many believe that one-to-one relationship is an ideal-- where the current societal affairs are reflected in a more direct manner in the art being created. This is also justified by those who object to the arts being too aloof from the humdrum of daily existence and realities.

The relationship as is evident in this book is far more complicated, complex and totally defies the one-to-one equation. It can be said that the rise of Urdu poetry is literature characterised by an age in turmoil. While the Muslim rule in the subcontinent, in pomp and circumstance, had few rivals, the medium of expression was Persian (with the dialects too being written in but seen as a minor tradition). As the canopy of the Empire was torn and became shredded, Persian dominance declined and the dialects became more active to be recognised as a legitimate vehicle for expression and gradually given a proper place both as literary genres and language.

The destruction of Delhi gave proportionate importance to the erstwhile provinces that became the centres of power and patronage. The Urdu poets, travelled to and fro seeking patronage, some got it, others pined for it being not worthy of their stature.

But it is questionable whether the poets saw the world, constructed about four hundred years ago, falling apart with a commensurate realisation as to what was happening. Probably not, because the poets or the people with insight were not in love with what was being lost as they were also not in lure of the anarchy that was being let loose around them.

In other words, there was no coherent approach to the crises that were erupting all over. There was no proper sense of national sentiment, neither was there a conviction about the justification of the monarchy or the rule of absolute authority. Hence, the author is not very convincing, for he has premised two assumptions which did not exist in any concrete shape. One, that the question of loyalty should have been derived from one’s association with religion; and two, that it was the love of the land that should have been the prime reason for the poets and the people to rally around.

The colonists had captured Bengal in the middle of the eighteenth century; Delhi too had become a titular monarchy by the beginning of the nineteenth century. The other seemingly independent states like Awadh and Hyderabad Deccan, too, were quite beholden to the rising power and authority of the various colonial powers interplay in the subcontinent. Punjab had been lost to the Sikhs by the middle of the eighteenth century and what was left was a spectacle in disintegration. All of this found an amazing spread in the entire body of Urdu literature, because it prospered in that era. The lack or absence of a rudder was the basic question raised by the poets. There was no rudder and if the author thinks that there was one in the puritanic interpretations extended by Shah Waliullah, he is simply overstretching its importance.

The vast array or the mosaic was too complicated for any definitive design and new political realities, like the Hindu dominance in sheer numbers, was glaringly becoming a crucial factor. The author also seeks valiantly to prop up the unity that the Muslim rule afforded, and in that, betrays the contradiction within the Empire, especially Aurangzeb’s use of force to arrive at one. In the process he overstretched himself and his rule to ensure a permanent tailspin of decline.

Nevertheless, the book throws valuable light on the works of both the major poets and those that were not that well-known, as one got to know through their poetry their reaction to what was happening. It appears that most were reacting to the situation that was foundering around them and seeking temporary refuges in the states, hoping those to be of a more permanent nature. It also points towards the various fissures that became huge and were not to be bridged, no matter what. The poets were at the mercy of the circumstances unleashed on them.

The best thing about the book under review is its price, which is minimal given the price of books which are being marketed these days. It is becoming increasingly difficult for the genuine reader to purchase a book because of the prohibitive costs involved. Minus the reader, the book is only a commercial venture between the publishers and bulk purchasers, who could be anyone from the libraries to institutions where books are stored rather than read.

The price tag is low because the book has been published by an organisation which is publicly funded. But many such organisations-- propped up from time to time getting grants from the government for publication of literature, considered to be of a serious nature-- either do not get a publisher or if published, result in an expensive product. Some of these organisations have not been able to publish consistently as the inflow of funding has been rather inconsistent. When the times are good, however, the spurt of activity increases and books are published at a faster rate.

Usually with such institutions, the problem is that of distribution and of making the copy accessible to the reader. Marketing of books has been their weakest point, as it is known to happen that stacks of published books rot in storages for years and then are sold as garbage or waste or junk. It appears that in the last few years, the National Book Foundation has been actively publishing good quality books and also consistently holding book fairs which have drawn plenty of book lovers.

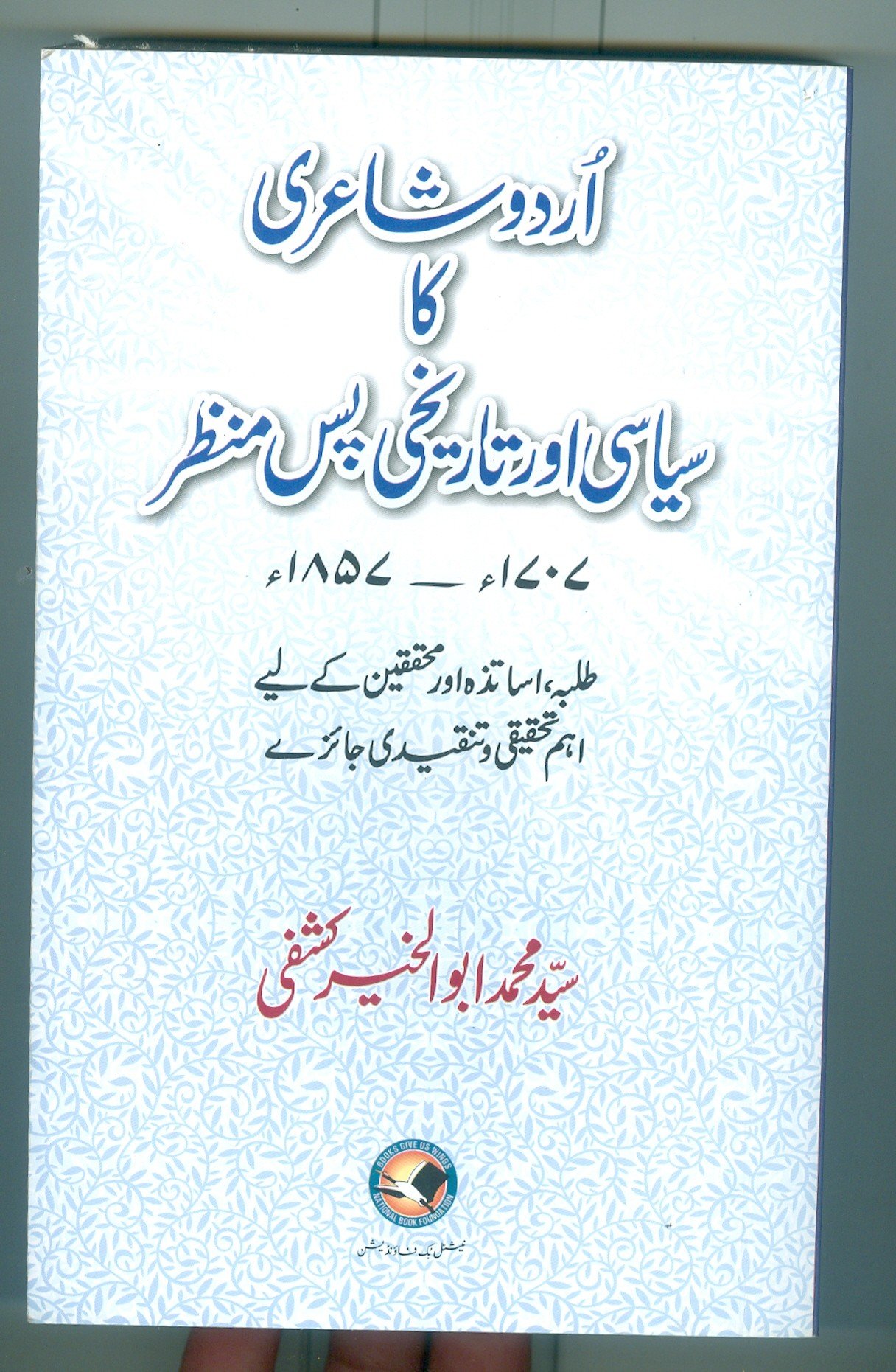

Urdu Shairi Ka Siyasi Aur Tareekhi Pasmanzar (1707-1857)

Author: Syed Muhammed Abul Khair Khasfi

Published by: National Book Foundation

Pages: 429

Price: Rs290