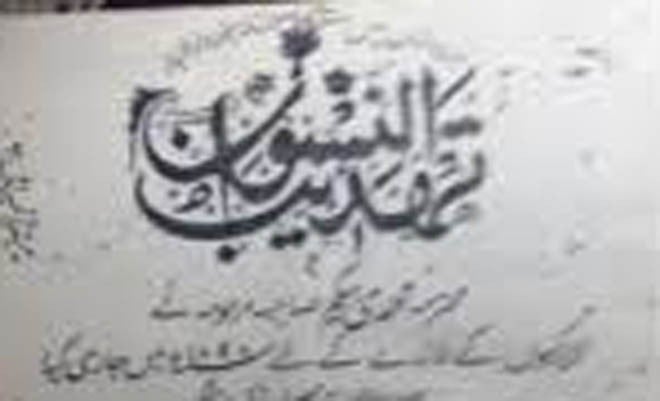

In the previous article, I had started by trying to understand the place of women in the South Asian Muslim imagination. I discussed the magazine Tehzeeb-i-Niswan that he published under the editorship of his wife Muhammadi Begum. I now wish to return to the contribution made by Mumtaz Ali in his book Huqooq-i-Niswan by first acknowledging the tremendous academic work done by Gail Minault in highlighting his work. When publishing the magazine, he also started the publishing house ‘Rifah-e-Aam Press’ in 1898, which was one of the first publishing houses owned by a Muslim in Lahore.

My point here is that Mumtaz Ali and his contributions must be seen in light of the colonial concept of modernity. Whereas Mumtaz Ali himself acknowledged his staunch rooting in the tradition of Deoband, I want to advance the view that even religiously conservative movements like Deoband and Arya Samaj were a direct result of the colonial propagation of modernity. Either as a reimagining of Western modernity as articulated in Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Syed Mumtaz Ali or in the reformist agenda of Deoband, the defining feature of social and political life in nineteenth and twentieth century subcontinent was the idea of modernity.

Most significantly, Mumtaz Ali questioned the idea of inherent and divinely ordained male superiority over women. He had developed a scientific method of argument through several public debates with Christian missionaries, and used it to great success in his prose. In Huqooq-i-Niswan, he identified eight traditional arguments advanced through history for men’s domination and repression of women. These arguments included men’s greater physical and intellectual strength, their supposed superiority as granted by religion, and in the case of Islam, men’s testimony having twice the weight as women’s, as well as a daughter’s share in property being half of the son’s. Mumtaz Ali rebutted all these arguments, a truly revolutionary and modernist thing in turn-of-the-century India.

Mumtaz Ali argued that greater physical strength did not automatically grant greater privilege to men. He stated that a donkey could carry more weight than a man, but that did not make a donkey superior. Men, therefore, could not assume the natural and divine right to be rulers. As a sign of the times, he argued that the contemporary female monarch of the British empire, Queen Victoria, ruled with great wisdom and justice.

This rebuttal represents a man whose mind was trained in the Western modernist idiom of humanism and gender equality. It also speaks of a man who realised the exigencies of his times, and while being trained in a conservative tradition like that of Deoband, he still believed in the progressive reformist agenda that colonial empire projected as the raison d’etre of its rule.

This was an important turn in colonial India because Christian missionaries made it a point to highlight Indian Muslim society’s regressive and repressive attitude towards women. Since British society generally propagated its pro-women, liberal ideals in its colonies, colonial subjects also felt obliged to borrow the colonial idiom for expressing their ideas.

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s embrace of English education was the starting point. Unlike Sir Syed’s close associate Deputy Nazir Ahmed though, Mumtaz Ali did not believe in women being confined as inferior beings. He believed that women deserved equal social space and had equal rights. This was what caused his contemporary Muslim scholars to question his ideas.

The reformist tradition has focused on two things mainly. For one, the rationalisation of Islamic religious law, which led to the disavowal of customary accretions and a return to the text; the Dar ul Ifta of the Dar ul Uloom Deoband which issued religious decrees was an important aspect of this reformist tendency. One sees this in Mumtaz Ali in his revision of women’s status in the light of Quran. Mumtaz Ali’s very significant claim was that the status of women as practised in Muslim society was the result of social customs, rather than religious law.

This, however, has its own contradictory caveat, and brings me to the second aspect of reformist tradition. While Huqooq-e-Niswan and Mumtaz Ali’s entire work seems to be progressive in its treatment of women’s rights, his stance about the revival of the text is an example of the de-historicisation that is a significant undercurrent of reformist movements. By arguing that customary accretions -- that is the customs and practices that have become part of a religious tradition in a specific cultural context -- are an aberration of textual authenticity, Mumtaz Ali and other reformists were paving the way for a reversal to more rigid systems of interpretation.

Thus, Ijtihad, which could be a truly revolutionary and progressive reinterpretation of religious law, became under colonial modernity and reformism, a tool for regressive interpretation. The real problem with de-historicisation is that it splits religious practice from social realities, and reduces religion to abstract ideology.

The British government also bestowed on Mumtaz Ali the title of ‘Shams-ul-Ulema’ in 1934 for his modern and progressive ideas and work. He passed away in 1935. Mumtaz Ali was a close confidant of Sir Syed. I wrote in the last article how Sir Syed got angry at Mumtaz Ali over the book Huqooq-i-Niswan, but it is also important now to mention that it was Sir Syed who was asked to choose a name for the magazine that Mumtaz Ali and Muhammadi Begum published, and it was Sir Syed Ahmed Khan who chose the title Tehzeeb-i-Niswan.

For six months, Mumtaz Ali sent 1000 copies of the magazine per week to the respected families of the city as mentioned in the Civil List, in the hope of finding subscribers for his magazine, but he could not find more than seventy buyers after three months. After Muhammadi Begum’s death, Mumtaz Ali’s daughter Waheeda Begum edited the magazine for a few years. Eventually, the magazine’s editorship fell to Syed Mumtaz Ali’s son, renowned Urdu man of letters and cultural icon, Syed Imtiaz Ali Taj.

Read also: Re-imagining Muslim women

In 1949, Tehzeeb-i-Niswan was discontinued. The question that intrigues me is if its legacy has been continued or not. I wonder if magazines like Pakeeza, Khawateen Digest, and Shua continued the tradition of reform and women’s social empowerment. A cursory perusal of recent publications indicates their consonance with larger social trends reflected in society through an increasing insecurity and closeted attitude.

With the rising contradictions of globalization and post-9/11 imperatives, Syed Mumtaz Ali’s reformist magazine would perhaps still struggle to find subscribers in the ‘respected’ families of Pakistan.

Concluded