A look at the devastating implications of a case that caused Pakistan’s dismemberment

Though there have been many conspiracy cases in the history of Pakistan, most of them never reached a conclusion. In the first two decades of Pakistan, the Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case (RCC, 1951) and Agartala Conspiracy Case (ACC, 1967) had far reaching implications for the future of the country. If the RCC set the tone for the suppression of progressive and secular politics in Pakistan, the ACC precipitated the rise of Mujibur Rahman as Bangabnadhu (Friend of Bengalis) and expedited the disintegration of Pakistan as a united country consisting of two wings i.e. East and West Pakistans.

Agartala Conspiracy Case surfaced in 1967 but its formal proceedings started exactly 50 years ago in the summer of 1968. Before discussing the ACC itself, some background is in order. Erstwhile East Pakistan -- that was initially called East Bengal -- had 55 per cent of Pakistan’s population. After the creation of Pakistan, Governor General MA Jinnah and Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan did not come from the eastern wing. There were leaders such as Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (1892-1963), Khawja Nazimuddin (1894-1964), and AK Fazlul Haq (1873-1962) who had the character and stature to become prime minister. But Jinnah, the governor general and president of the Muslim League, chose Liaquat Ali Khan to be the first prime minister of Pakistan.

This was much before Mujib became a prominent leader of Bengalis. The three great leaders of East Bengal i.e. Suhrawardy, Nazimuddin, and Fazlul Haq represented the vast majority of the Pakistani people. They also commanded high respect and admiration from non-Bengali Muslims too. Sadly, all three of them were declared traitors, humiliated, and deprived of their right to be part of the governing machinery in Pakistan. Jinnah himself had topsy-turvy relationship with the three of them, though he tolerated them as much as he could. That was perhaps one reason none of the above was deemed appropriate to be the prime minister.

Though after Jinnah’s death, Nazimuddin did become the second governor general and then the second prime minister of Pakistan, he was the first of the three Bengali leaders, prior to Mujib, who was treated shabbily by the civil and military bureaucracy dominated by non-Bengalis mostly living in West Pakistan. When Nazimuddin became prime minister in 1952 after the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan, he was allowed to retain that position just for 18 months. Even during that period, constant efforts were made to destabilise his government by inciting religious violence and creating food shortages. Finally, he was dismissed by Governor General Malik Ghulam Mohammad in April 1953.

After the unceremonious exit of Nazimuddin, it was the turn of A K Fazlul Haq who had won a landslide victory in the provincial assembly elections in East Bengal in 1954. He had remained the PM of Bengal for six years (1937-1943) and now he was an elected chief minister who commanded absolute majority in the provincial assembly of East Bengal. That was a big defeat for not only the Muslim League but also for the establishment that was not ready to accept a Bengali leader in such a strong position.

Within two months after he assumed power as the chief minister of East Bengal, some of his statements were misinterpreted as he wanted to establish good relations with India and especially with West Bengal. After Nazimuddin, A K Fazlul Haq became the second Bengali leader to be dismissed. Nazimuddin was spared the charge of being a traitor, as he was mercifully labeled only as an incompetent prime minister. Haq was charged with much more serious crimes. He was called an anti-Pakistan politician, an Indian agent, and a leader who wanted to divide Pakistan.

His only crime was that he wanted to live in harmony with India and wanted to provide an alternative narrative of peaceful coexistence as opposed to the belligerent narrative of the establishment. The third in line was H S Suhrawardy. When he was sidelined within the Muslim League by Liaquat Ali Khan and other leaders of West Pakistan, Suhrawardy co-founded and joined Maulana Bhashani’s Awami Muslim League that later on became Awami League to accommodate non-Muslim citizens of Pakistan. During the first decade of Pakistan, Suhrawardy followed a policy of reconciliation with West Pakistan.

He even accepted the Parity Formula propounded by the One-Unit scheme that deprived East Bengal of its majority in the parliament that never came into being. He played an instrumental role in accepting the 1956 Constitution though most Bengali leaders had serious reservations about it. Suhrawardy became the fifth prime minister of Pakistan in 1956 but his fate was no different from that of Nazimuddin or Fazlul Haq. Nazim and Haq were dismissed and Suhrawardy was forced to resign. The first president of Pakistan, Maj-Gen Iskandar Mirza -- himself from Bengal but a tout of the establishment -- did tremendous harm to efforts to establish democratic norms in the country.

Just like what Ghulam Ishaq Khan did 30 years later from 1988 to 1993, Mirza had done almost the same in the mid to late 1950s -- constant bickering and manipulation with politicians to destabilise one government after the other. Suhrawardy resigned in 1957 but his real ordeal began when Gen Ayub Khan took over as the chief martial law administrator and appointed himself president in October 1958. Gen Ayub was bent upon expelling all leaders from the political landscape of the country.

When Ayub Khan asked politicians to voluntarily retire from politics or face court cases most politicians obliged but Suhrawardy defended his case. Ayub humiliated him so much, repeatedly calling him a traitor, an Indian agent, and anti-Pakistan that Suhrawardy decided to leave the country. Suhrawardy died a broken man in Lebanon where he was living in exile. ZA Bhutto, who was a right-hand man of Ayub was also instrumental in giving mental torture to Suhrawardy and advising him not to step back in Pakistan again.

With the death of Suhrawardy in 1963, Bengal lost the second of its illustrious sons, the first being Fazlul Haq who had died a year earlier in 1962. The third one i.e. Nazimuddin died in 1964, and so the trio of the great leaders in Bengal came to an end, leaving an open field for Mujib to play his politics as he wanted. One is inclined to think that had our establishment treated the three great Bengali leaders with respect, Mujib would have been unable to incite the politics of separation that he ultimately did.

The five-year period from 1962 to 1967 i.e. the Agartala Conspiracy Case, saw not only the deaths of the three great Bengali leaders but also witnessed Gen Ayub Khan steal the presidential elections against Fatima Jinnah who was wholeheartedly supported by the Bengalis in East Pakistan. Massive rigging and manipulation of election results by the Ayub regime paved the way for further alienation of the Bengali citizens of East Pakistan.

With this background now we come to the Agartala Conspiracy Case that lasted for less than a year -- before being scrapped by its prosecutors in 1969 -- and left an indelible mark on the history of Pakistan.

Interestingly, in December 1967 when the first arrests were announced in the Agartala Conspiracy Case Mujib’s involvement was not mentioned. From the very outset most Bengalis considered this case as an attempt to discredit the growing Bengali demand for regional autonomy. The case brought some senior Bengali officers of the Pakistan civil service and the armed forces into disrepute. In January 1968, Mujib was also implicated in the case, though he had been in prison since May 1966 when he had announced his Six Points. Ayub Khan’s sole goal from the beginning had been to snuff out all democratic aspirations of the people of Pakistan and more so in East Pakistan.

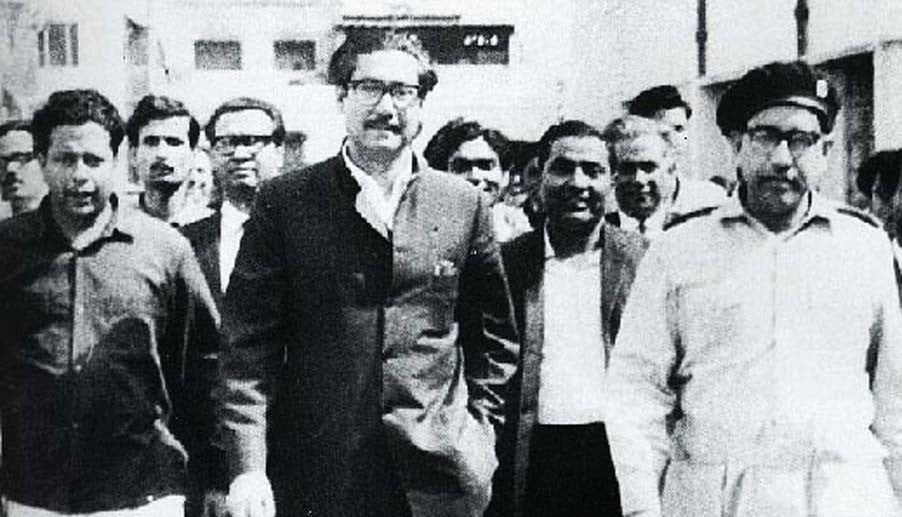

Somehow the establishment has always failed to understand that exactly the reverse happens when such attempts are made. This case gave a spur to Bengali nationalistic sentiments and Mujib soon became the voice of the Bengali people who remembered very well how the voices of Nazim, Haq, Suhrawardy, and Fatima Jinnah had been silenced. Ayub Khan had decided to convene a special tribunal as opposed to the normal judiciary to try the case. The head of the tribunal was the Punjabi Justice Sheikh Abdur Rahman (S A Rahman) from Wazirabad.

Justice Rahman (1903-1990) was an establishment’s judge who had turned a blind eye to the election rigging by Ayub Khan; and had also served as chief election commissioner for a brief period of time, and later also became Chief Justice of Pakistan. To give credence to the case, in the ACC he was supposed to be assisted by two Bengali judges: Justice Mujibur Rahman Khan and Justice Maksumul Hakim. As is the undemocratic practice even now, the accused were kept away from their families in a small room in cantonment.

Rumours spread that the accused, including the CSP officers, were getting vicious treatment in confinement. Hearing in the case opened in June 1968 i.e. seven months after the accused were seen in public. A very large number of state witnesses and approvers were listed by the government. The total number of detainees in the case on charges of complicity was over 1500, all coming from various professions. Thirty-five of the accused were put on trial and 232 became, or were compelled to become, state witnesses. Right from the beginning, the case appeared to be collapsing because a number of state witnesses turned hostile, and claimed that the authorities had tortured them to turn approvers.

Some of them broke down in the court, generating a wave of sympathy. In addition, the political movement outside became increasingly frenzied against Gen Ayub Khan who made the mistake of celebrating his decade of development in 1968. Crowds of Bengalis also demanded the dropping of the case.

The entire case was based on the premise that the accused Bengalis had sought or attempted to seek Indian help for the liberation of East Pakistan. It appears that there was some truth in the accusation and after the independence of Bangladesh some of the accused did admit about their involvement in the conspiracy. But the manner in which the said case was handled and scrapped injected a new life into the freedom struggle of the Bengali people.

By 1969, Gen Ayub had lost his grip on power and with the opposition in its high tide and even the army chief conspiring against the president, a round-table conference with the opposition was proposed. Mujib refused to attend unless the case against him was abolished. And so it was done, Ayub lost the game but the Agartala Case and its mishandling by the state, strengthened the hands of the separatists. The last straw was put by Gen Yahya when he refused to acknowledge the election results of 1970. In 1971, East Pakistan emerged as an independent country after an operation by the Pakistan armed forces led to the Indian intervention.