Nasim Zehra’s book on Kargil is a valuable addition to the existing scholarship on Pakistan’s wars and military decision-making -- a brave attempt indeed to contest nationalistic official narratives

The outline of the events from April till August 1999, called Kargil and codenamed Koh Paima (KP), are spread in many memoirs, newspaper reports and interviews and, of course, in the chatter of drawing rooms and academic spaces.

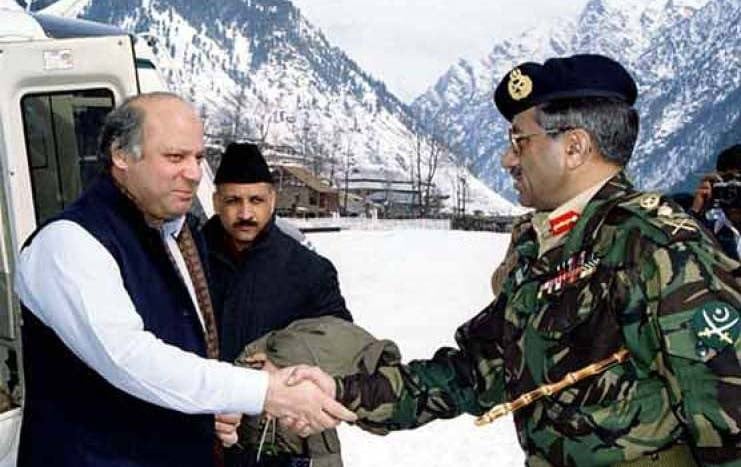

While Prime Ministers Nawaz Sharif and Vajpayee were making apparently sincere efforts to make peace between India and Pakistan, four generals of the Pakistani army -- General Musharraf (Chief of Army Staff), Lt. General Mahmud Ahmad (Corps Commander 10 Corps), Lt. General Aziz (Chief of the General Staff) and Major General Javed Hasan (Commander Force Command Northern Areas FCNA) -- made the plan to advance and occupy posts about seven kilometres inside Indian Administered Kashmir. These posts had traditionally been vacated in the winter by Indian troops who were taken by complete surprise when they came back according to schedule to reoccupy them in late April 1999.

Since the posts dominated the road to Leh and Ladakh and Pakistani troops could now fire upon convoys carrying supplies to the troops, this was a highly threatening move for India. India reacted by bringing in heavy artillery and later the air force to lodge the intruders. Eventually, Nawaz Sharif went to the United States to ask for help from President Bill Clinton to mediate in a conflict which, Sharif felt, could spiral into a war between two nuclear-armed countries. The price for peace was, of course, a commitment to withdraw from the heights still held by the Pakistani troops. This withdrawal took place in July and August, and was seen as humiliation in Pakistan.

Meanwhile, the generals who had planned KP felt apprehensive that the PM would take action against them for launching such a disastrous operation and that too at a time when peace seemed at hand. They, therefore, prepared to launch a coup d’etat against Nawaz Sharif. This coup was eventually launched in October 1999 when Nawaz Sharif decided to retire General Musharraf who, as it happened, was flying back from Sri Lanka. This story, which was believed to be true by most scholars in the world including those who are stigmatised as being liberals in Pakistan, was vehemently denied in Pakistan. Nasim Zehra, at least in the early Musharraf years, was one of the supporters of the ‘official narrative’ that, in her own words, ‘the Mujahideen were the ones doing the fighting in Kargil’ (p. 12).

The present reviewer remembers Nasim Zehra’s vehement support of this narrative and would like to commend her frank acknowledgement that it was when she did more research, she found out this narrative was wrong. It requires much moral courage to admit one’s ignorance and mistakes and it would be mean not to praise her for having begun the book with this clarification.

Nasim Zehra begins with the accession of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In this she refers to the principle of reference to the will of the people, but, in fact, there was no such agreed principle otherwise Pakistan could not have accepted the accession of the state of Junagadh (a Hindu-majority state ruled by a Muslim Nawab). She is right about the use of force, however, and also that India got away with it in both Junagadh as well as Hyderabad. This is just the strategy used by Pakistan in 1947 (encouraging and supporting the Pashtun tribesmen to take over the state by force) and in 1948 (with the help of the army). What is not acknowledged by any Pakistani strategist or planner is that such use of force, besides being morally wrong from the point of view of international law, is not pragmatic for a state which is small and has a leaner economic base and military strength.

This is just what happened in the planning for the 1965 wars and then in Kargil. Two assumptions of Pakistani decision-makers made such actions possible: first, that India would not go for full scale retaliation to Pakistan’s military operations in Kashmir across the LOC; and second, that Pakistan can militarily counter India without suffering unacceptable loss. Nasim Zehra gives the most detailed account available so far about the decision-making for Kargil in which both are manifest. When junior officers asked their seniors inconvenient questions: ‘what if our cover gets blown’?; ‘what if we are caught’? etc. they were told to obey orders and, says Zehra, ‘steeped in the discipline of obeying the chain of command, they did exactly that’ (p. 98).

The usual standard operating procedures (SOPs) were dispensed with and in one meeting General Musharraf, referring to India’s abortive war with China in 1962, asked whether this operation would not suffer a similar fate. At this Generals Javed Hasan and Mahmud both said their ‘necks’ would be on the line. Musharraf, who was the COAS, said it would be his ‘neck’ rather than theirs (p. 119). Zehra points out that General Javed Hasan would often say: ‘the timid Indian will never fight the battle’ and that they (the Indians) would not know ‘what hit them’ (p. 124).

She concludes that ‘leading the charge for Operation Koh Paima were simplistic and patriotic mindsets’ (p. 124). She also gives dissenting views of army officers who knew even at that time that the operation was ill-conceived but those who were serving, could not express such a dissenting view.

Among the questions which were discussed in the Pakistani press at that time, and have never been settled, are whether the legal head of the government, the prime minister, was informed about what had been planned. Nasim Zehra’s analysis after a detailed consideration of evidence is that the PM was not informed till after the operation was in full swing. The generals, whom Nasim Zehra calls ‘the Kargil clique’ and even ‘the gang of four’ (p. 151), told the PM that they were responding to Indian shelling for which an alternate route was required and that they wanted to support the Kashmiri Mujahideen in the Valley. She clarifies that in May, Generals Aziz and Musharraf shared a telephonic conversation which ‘left no doubt that the Kargil clique had undertaken Operation KP without specific clearance from the prime minister’ (p. 445).

She also says that in November 1998 the PM had ruled against the use of force by the regular army in Kashmir so it was not likely that he could allow such an operation later. However, when he visited the area Nawaz Sharif did make statements supporting freedom fighters. It is not clear, however, whether he actually understood what was really happening.

According to Nasim Zehra very late in the conflict Nawaz Sharif asked Musharraf ‘Did you cross the LOC?’ To this Musharraf replied ‘Yes, Sir, I did’. The PM then said ‘On whose authority?’ and Musharraf replied ‘On my own responsibility and if you now order, sir, I will order troops’ withdrawal’ (p. 165). It was then that Nawaz Sharif said he would support the army. In any case, with the public believing in Indian aggression and that the Kargil heights were occupied by the Mujahideen and not the army, no civilian leader could have done anything else.

The other question is whether it was necessary to withdraw Pakistani troops by going to the US. The author says that about half of the major peaks had been evacuated by Indian firing and the others could hardly have sustained the unremitting onslaught of the artillery and the air force. Moreover, it was difficult to provide the troops with food and ammunition especially as winter was drawing near. Nawaz Sharif understood the real plight of the troops when he visited a hospital in Skardu. Here the bunks were ‘packed with severely injured soldiers, suffering from the traumas of broken bones, amputated limbs, head injuries, etc’. This was a sight he did not expect and ‘he looked crestfallen and teary-eyed as he walked around and comforted the wounded soldiers’ (p. 235).

Eventually, Nawaz Sharif decided to risk no more lives nor did he want war with India and sought US intervention. However, the planners of the operation encouraged rumours that the PM had lost a war which they were winning. Of course, the opposition parties, especially those which opposed peace with India, spread this disinformation in the country and the PM had to bear the brunt of public disillusionment and fury.

Besides providing the most detailed description of the Kargil operation in all its phases, Zehra has also provided a blow-by-blow account of Musharraf’s coup of October 12, 1999. She says that Nawaz Sharif was confident that he could remove his army chief being the commander-in-chief in legal parlance. But this was naivety given Pakistan’s history of the dominance of the military in the country’s politics. However, it was the army which sent in troops from the 101 Brigade after the PM had sacked his army chief and appointed a new one.

The fateful decision to make Musharraf’s flight land somewhere other than in Karachi where his supporters were bound to bring him to power, was taken then. The author makes the point that the Civil Aviation Ordinance of 1960 did give the PM the power to divert planes in certain emergencies (p. 407). The PM did allow the plane to land in Nawabshah but, of course, by that time the corps commander in Karachi had taken over and the plane landed in Karachi and the rest is history.

From Nasim Zehra’s detailed and painstaking reconstruction of the events, it is clear that Kargil operation was an ill-planned and illegal military action which undermined genuine efforts of peace from both sides. Moreover, it paved the path for yet another ten years of military intervention in the politics of Pakistan. This intervention was not because the civilian leadership was doing something wrong but because the military leadership wanted to escape the consequences of its mistakes. This makes this book a valuable addition to the existing scholarship on Pakistan’s wars, military decision-making, civil-military relations and military rule in the country.

The author has bravely attempted to tell the honest truth like a good scholar whose real loyalty is to truth rather than nationalistic official narratives.

I must also point out that the book would be improved by good editing. First, there are far too many repetitions which make for a prolix account. In my view, at least a hundred pages can be cut out without compromising the veracity of the narrative. To make matters worse the binding is not good and pages fall apart in one reading. To be fair to the author, these are not her faults. Indeed, one can empathise with her frustration at these avoidable issues. Nor do they detract from the worth of the book which lies in its excellent use of sources and clear analysis and, above all, the scholarly commitment to truth even when it carries risks.

I recommend the book to strategists, historians, media persons and the ordinary reader without reservations.

From Kargil to the Coup Events that Shook Pakistan

Author: Nasim Zehra

Sang-e-Meel, 2018

Pages: 532

Price: not indicated