The charm of a letter often lies in the simplicity of the process, than the elegance of the final product

On the 27th of May, I received a letter. It arrived in an unsealed, off-white envelope about the size of a letter given on Eid. Inside, there was a recycled sheet ripped from the top and no money. It began, A Sunday Afternoon, and was addressed to Arsalan Isa Esquire.

The word ‘esquire’ loosely means an unofficial title of respect, with no precise significance. An ironic word then, meant to uplift those who haven’t earned an accolade, but are owed a gesture. A word best used sarcastically, but here it was curtsying with the best of intentions, as I know it.

It was written in cursive. The words were corkscrew insects. They could have been dragonflies, daddy longlegs or beetles. They were tense tendrils, and in this tension, another layer of meaning was exposed. There wasn’t much attention paid to penmanship. And at first, I couldn’t decipher the letter.

But it had been written in ink it had been touched. A presence was transferred into those handwritten words. In that letter I didn’t just have the words, but their squiggly corporeality. There was vertebrae, exoskeleton, and bowels. The purpose and content of the letter was nothing extraordinary, it simply suggested a time and place for a routine meeting.

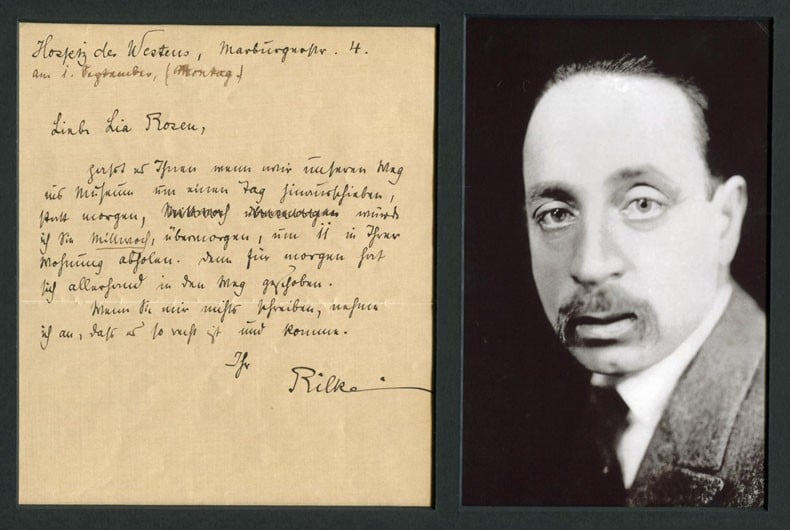

Between 1902 and 1908, Franz Xaver Kappus, a young cadet with an inclination for poetry, wrote diligently to Rainer Maria Rilke, seeking guidance and strength. He opened his heart like a garden faucet; and Rilke responded tenderly, in his Letters to a Young Poet. Rilke’s penmanship was flawless. The letters are meticulously composed. Beautiful and controlled, they are evenly paced, flamboyant where necessary, cautionary where advised. They are packed with sound and trite advice on how to write and live. The kind you read in a manual: this is the best way to safely operate your microwave; this is how many glasses of water you need to drink for your liver, skin, and metabolism; this is what you should and should never say to your lover.

Good advice is easy. It’s almost sanctimonious, which makes it lifeless, as well as alienating. There’s distance and condescension to it. That’s dangerous. The best advice is when someone talks self-indulgently about themself, and in that monologue the truth whistles. Mistakes, struggle, regret, torment, insecurity, and overcompensation. These are relatable. Don’t advise against putting a hand in the fire. Share how you burned, how the skin fried like a morning pancake. Through pain, we experience empathy.

A good letter is a churning stomach. It’s inflamed and wrathful. A summer wedding with the extended family included. It’s raw, tumbled together, doubtful, exposed, and vulnerable. The vulnerability is essential. The best letter is at war with itself. There’s agony and revolt. Pretty pictures and pristine sentences are accidental. Purity is found in process. Process is messy.

In his letters to Kappus, Rilke tries to convey that emotional wideness is reducible. He tries to reach across it, guide and address it, but the wideness only grows, because nearness is only ever experienced in suffering and in love.

The letter I received, which was not an Eid letter, which had no money or kind words, was a better letter. I felt the mistakes. The scribbled lines. The poor penmanship. The crossed out words. The blotchiness. The trembling. The emotions. I saw the violence the pen exerted. It was a better letter because it didn’t try to be what it is was not.

Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet are majestic, but tedious and affected. The words are polished, soft-leather brogues. They’re comfortable and easy to walk in. They amble with a cosmopolitan and bourgeois gait, but head towards an uncertain destination. Rilke admits, "Nobody can advise you and help you, nobody." It’s in this wonderful solitude, where words are meaningless that we find ourselves.