The bilateral, more aptly military infused, relations have once again come full circle, suggesting they still lack a solid underpinning of shared interests

How can one explain the roller-coaster character of the US-Pakistan relationship, marked by so many ups and downs? mused Ambassador Dennis Kux in his venerable 2000 book Disenchanted Allies. He grappled with the question by observing that "over the years US and Pakistani interests and related security policies have been at odds almost as often as they have been in phase".

The United States and Pakistan were, broadly speaking, on the same wavelength during the Eisenhower, Nixon, and Reagan presidencies, he points out. Still, the Pakistani side, whenever relations with America peaked, were spearheaded by its military rulers. During the Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, Bush, and Clinton administrations, however, policy differences were significant, and bilateral relations mostly sluggish.

This verisimilitude notion became the basis of the misconception that the United States always supports military dictators in the country. "It’s just circumstantial," one State Department official said to me while discussing the grounds of the above notion.

A senior high level Pakistani diplomat at the embassy agreed. "Pakistan has a strategic location, and the situation has usually been thus that when the US engaged to address its security concerns, Pakistan happened to be under one military rule or another," the diplomat said.

In total, over the past seventy years, there have been four instances when the relationship between the two countries was at its best. Out of these, three occasions were when the military had already taken over the country, with or without the knowledge of Washington. The story of civil or military rule in Pakistan reflects the state of the country’s relations with the US.

Initially, the United States was hardly interested in Pakistan’s cooperation against the supposed Communist threat. The relationship kickstarted on the faulty premise that the US could have security concerns in the region that should be countered by aiding the Pakistani military. "The government of Pakistan has now asked the United States to grant military assistance," the U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower said in a statement issued in February 1954. A year earlier his administration had approved the Major Defense Acquisition Program agreement. They were lured in by the then Pakistan’s army chief General Ayub Khan when he submitted, "Our army can be your army if you want us".

After becoming the first army dictator, Ayub pleaded to the Americans, "Recent developments have, if anything, strengthened Pakistan’s faithfulness to its alliances. Pakistan is more than ever on the side of the free people of the West. Continuance of US aid is a matter of life and death to Pakistan."

Once the main characteristic of the relationship as a client state was established, it was much easier for General Agha Muhammad Yahya to navigate through that as well. The bilateral security agreement signed in March 1959 was revived and reinvented in October 1970 as a "one-time exception" to permit Pakistan to procure about $50 million worth of replacement aircraft and some three hundred armored personnel carriers.

As fate would have it, the economic and development initiatives could never be prioritised. During Bhutto’s tenure the US provided food commodities including thousands of tons of wheat and granted loans, yet the core issue between the two governments remained lifting the arms embargo, and exploring weapon exports. "It was not that Pakistan wanted toys … Pakistan sought sufficient arms to permit it to defend itself," was the propped up explanation to Henry Kissinger by Bhutto.

The third martial law administrator, General Ziaul Haq, first ignored the West’s chagrin over general elections or democratic values; and later asked US official Robert McFarlane, "Why don’t you ask us to grant [you] bases?" The arms support and other financial aid that followed to fight off communism substantially bolstered the confidence of the Pakistan army.

Once Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan, the military provisions to Pakistan army naturally diminished. The US, however, was motivated to provide development and economic support, rather than giving stable source of military aid, against certain conditions.

The relationship conundrum stems from the fact that civilian governments in Pakistan, much like all the other succeeding ones that followed for a short period, could not keep the commitments made by military leaders to the international community to secure military related deals. Whenever promises were broken, relations soured. In return the US was blamed for not supporting Pakistan all the way, hence betrayal. Former US Foreign Service official, Teresita Schaffer calls it the ‘art of the guilt trip’.

Because the army dominates the policy process on a range of issues including foreign relations, the United States has to ultimately drift towards it. The military as an institution generally prefers dealing with the Pentagon anyway -- a supposed ‘mil-to-mil’ relation while keeping civilians on the curb if not out of the way. This approach helped the army maintain its influence on civilian institutions and the United States managed to address difficult issues with the military directly. "Sometimes, this is necessary and appropriate, but, excessive reliance on the military to do civilian business tends to further undercut the effectiveness of Pakistan’s civilian institutions,"

Teresita Schaffer suggests in her well researched and impressive book How Pakistan negotiates with the United States "There is a fine line between keeping Pakistan’s most powerful institution in the loop and reinforcing the disproportionate influence and political leadership role of the army."

She also emphasised that the US negotiating process is riddled with deadlines and technicalities, which presents a challenge for the less legalistic and less deadline-driven Pakistani military.

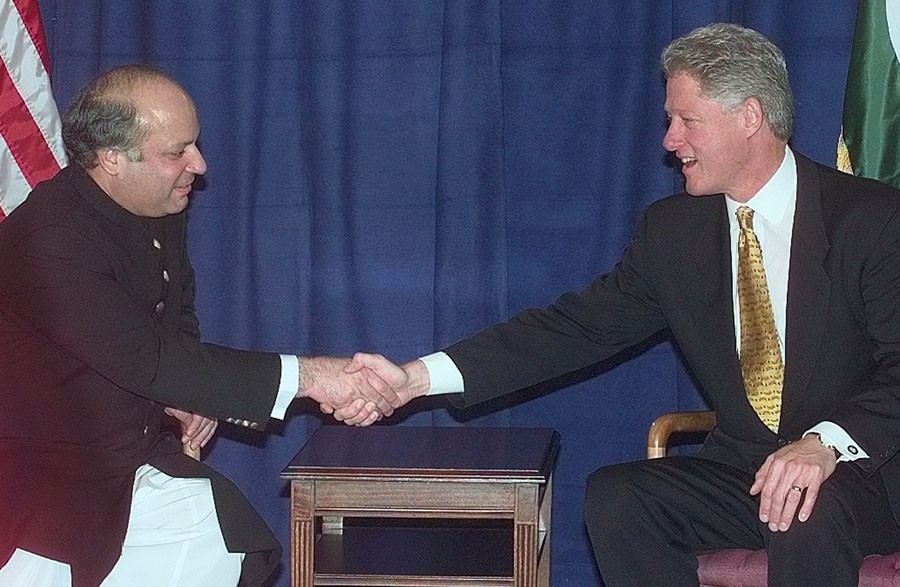

When General Pervez Musharraf ousted Nawaz Sharif in 1999, the Clinton White House reaction was negative, resulting in sanctions legally required in the case of the overthrow of a democratically elected government. Two years later, the Bush administration had to deal with the same Musharraf ruled Pakistan, giving him leeway through secret agreements to achieve missions in Afghanistan. He offered military bases, airports, seaports, dry ports and a passage through the length of the entire country in exchange for funds and arms. The war in Afghanistan proved an opportunity to further cement the military-to-military relations between the US and Pakistan.

Washington, once again, remained continuously troubled by the weak democratic system in Pakistan, risks of military interference in state institutions, and the threat of growing extremism in the country. In the midst of this, President Obama tried to correct the course and expand the bilateral cooperation to civilian institutions. Hillary Clinton, as Secretary of the State, acknowledged US mistakes and misgivings of the past publicly.

The administration approved a first long-term hefty civilian aid package to support the new civilian government post Musharraf regime. Yet the legislation, named Kerry Lugar bill, faced massive resistance from Pakistan’s military leaders. John Kerry had to fly to Islamabad to do the necessary firefighting.

On one occasion, Kerry sat for five hours with General Kayani over dinner. "We want to give you this money, we want to change the nature of our relationship. … but to be able to do that, you guys have to be sensitive to how you’re going to be perceived if you continue to do some of the bad things that you have been doing," Kerry told Kayani, according to a senior official quoted in the book War on Peace: The end of diplomacy and the decline of American influence, penned by Ronan Farrow.

Farrow was part of the diplomatic corps then, and noticed that the situation held a mirror to the deep problems in the relationship. While the conversations between spy chiefs and generals flourished, the intended broader relationship had become a petri dish for paranoia and suspicion, Farrow writes.

The Kerry Lugar bill, Congressional Research Services analyst Alan Kronstadt told Farrow, was a grand strategic attempt to address the perception that the US was only engaging with the Pakistani military and didn’t care about democracy or the Pakistani people. Eventually the aid was released, but with the army overseeing the narrative and purpose of it.

The US’s sincere intention clearly failed to leave a mark and the blame fell on the representatives of the civilian government for scandals like granting unauthorised visas to Americans or issuing unsanctioned memos.

Read also: Is the dinner over

After that, the broader civilian relationship between the two countries could not take off. Pakistan’s economic assistance slowed down and its diplomatic isolation heightened. Lately, the Trump administration has halted the security aid, however his newly appointed Secretary of State Mike Pompeo opened up lines of communication with Pakistan’s army chief to renew the commitment in bringing the Taliban to the table to conform with the rules proposed by the Afghan government.

The bilateral, more aptly military infused, relations have once again come full circle. The volatility of the relationship suggests that their ties still lack a solid underpinning of shared interests and could stay the same in the foreseeable future.