Revelations in memoirs, biographies and interviews have a tremendous significance for historians, they invariably challenge and correct narratives offered by official histories

Amartya Sen once characterised South Asians to be an argumentative society. In his book The Argumentative Indian he explores ancient Hindu texts pointing out that a certain scepticism which made debate possible was inherent in them. Although Sen looks at the Hindu tradition, the same could be said about the Islamic one, at least in the subcontinent. Here too there was endless debate between Shariat (the Islamic law) and the Tariqat (the mystic path towards moral excellence and spiritual elevation). The Chishti saints approved of music (sama‘a) while conservative preachers frowned upon it.

Urdu poetry is replete with these debates and, of course, our tea houses, parlours and village chaupals, jirgas etc carried on the conversation. Just take up a novel say by Qurratulain Haider and you will find the characters indulging in endless argument whether they are located under banyan trees or in a Cambridge college.

Indeed, it is fair to say that this debate has ended, at least on some issues because of fear - that of being accused falsely for blasphemy for instance - and this has caused much intellectual impoverishment in Pakistan. What has not stopped so far is political and historical discussion. Your gardener (mali) has his pet theory about Trump, Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif; the cook has another one; and of course, the Oxford-educated academic who dined at your table last night has yet another. Efforts are being made to outlaw even this debate and this is what is at issue.

The law that one cannot speak against the judiciary and the military is invoked to eliminate dissident views about politics and history, and this is a dangerous trend in Pakistan. First, it is used to target people one does not like. And second, such charges are paraded through the media and are defined so nebulously and confusedly that one is tarred by the brush of infamy and defence becomes nearly impossible. For instance, those who were after Nawaz Sharif for other reasons clutched at the charge of his being anti-state just because he repeated what many people had said, that non-state actors who attacked and killed so many people in Mumbai in November 2008 were ‘allowed’ [though the term is not clear at all] at some level by someone connected with the power structure. That is precisely what Dawn leaks had suggested.

One response to such allegations could be to investigate them more transparently and actually do something about making peace possible by changing patterns of behaviour. The other is to respond with the bell, book and the candle. This is what we do.

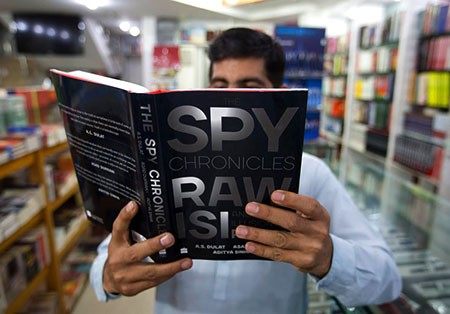

And, while the witch hunt against Sharif was in progress out comes General Asad Durrani’s book based on his talks with the RAW Chief A.S. Dulat. Now if this was not serendipity what is? So the witch hunt had to include him. Of course, at that time most people who waxed hysterical against the book had not actually read it.

This is why revelations in memoirs, biographies and interviews have a tremendous significance for historians. They invariably challenge and correct narratives offered by official histories. For instance, our children are taught that on September 6, 1965 India attacked Pakistan without provocation. But it is General Musa Khan’s book My Version (1983) which reveals that there was, indeed, an operation called ‘Gibraltar’ launched in August 1965 in which fighters were launched into Indian-administered Kashmir to bring about a popular revolt there. That it failed and Pakistan did not win the unwise 1965 War is confirmed by other revelations: Altaf Gauhar’s, Air Marshal Asghar Khan’s, the ambassadors posted in Pakistan and accounts by Americans, British, Indian and other witnesses.

Similarly, we know about alternative versions of 1971 through accounts furnished by Pakistani military officers, Indians, Bangladeshis and Americans, for instance, Gary J. Bass’s The Blood Telegrams, published in 2014. The official versions of history are aptly described as The Murder of History in Pakistan (1985) by K.K. Aziz whose other book The Pakistani Historian (2009), describes the official stooge who toes the official line, as the typical historian. So, the long and the short of it is that if we stop producing these revelations it would be impossible to write a credible history in Pakistan. Of course, one does not reveal everything and it is by checking and cross-checking all assertions that enable one to reach a possible version of the truth.

So what is so unsettling about Durrani’s book that the moral brigade is after it? In my opinion, it is primarily the fact that he is talking to the RAW chief and an Indian journalist, Aditya Sinha, who is converting their informal and frank talks into a readable account. The official version is that one should not indulge in such conversations at all. But the fact is that this is Track-2 diplomacy.

Diplomats in service cannot move from the official narrative, thus the need for this kind of interaction. Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri in his 2015 book Neither a Hawk nor a Dove describes so many off-the-record interactions in which the cause for peace in Kashmir was promoted. And, to give Kasuri credit, he did achieve something tangible in Kashmir during Pervez Musharraf’s rule. So the fact that the two spy chiefs talked to each other like gentlemen ought to be celebrated rather than castigated and vilified.

Then there is the charge that Durrani deviated from the party line, as it were, to express opinions one expects from liberal-humanists not army generals. Now, as the pundits think hanging is too good for the liberals, this condemns the poor general. Well, one lives and learns and generals are no exception. When they leave military service, they come to understand that they can no longer bury their heads in the sand and that there’s a world outside the barracks. They even form views which one does not expect to find in the pillars of the establishment, ironically this term is used for everybody except themselves by both Dulat and Durrani in the book.

Let’s examine this more closely. One such view attributed to Durrani is about Akhand Bharat. The term does not mean a United India ruled by Indians as Durrani uses it. On page 291, he says: "Right now it’s impossible to create a coalition or a union like the European Union, but at some stage we can think of a common currency, or laws applicable to when we develop the new South Asian Union: a Confederation of South Asia."

But he does mention that the armed forces be ‘integrated’ and reduced. Since the concept of integration is not clear it’s not possible to understand the distribution of power in this confederation. If it means something like the Schengen States then the symbolic capital may be Delhi (as Brussels is in Europe) but the nation-states would retain their governments and armies. If integration means joint commands, then it will eliminate the peril of nuclear annihilation but since it might increase the fear of Hindu domination it will be opposed by most Pakistanis.

The point is that Durrani does not say this is achievable right now. All he says is that "we can work on its elements, by softening the India-Pakistan borders" and make those in Kashmir "irrelevant", as advocated in Kasuri’s book and mentioned by Musharraf. As for the extremist Hindu concept of Akhand Bharat, even Dulat rubbishes it as nonsense. Basically, Durrani’s idea is to create a friendlier South Asia.

What is surprising is that Durrani says he spoke to Amanullah Khan who wanted an independent Kashmir and "never gave enough thought to his idea of independence". He is sorry for his attitude -- the apology does him credit -- and now says it is a possibility which can be considered. Dulat does not agree and evades the issue.

This is typical of the ‘establishment’ in both countries. Both have not bothered about the people of Kashmir but both want the land. Another thing which nobody seems to factor into the equation is that it is dysfunctional to talk of the former state of Jammu and Kashmir as one unit. It never was one unit. The area now called Azad Kashmir was liberated through a popular revolt by local people against Maharajah Hari Singh’s despotic rule. The Jammu area is now mostly Hindu. Muslims were removed forcefully from there just as Hindus were removed from the Western districts in 1947. The Kashmir Valley had its leader in Sheikh Abdullah who ruled by the consent of the Muslim population there. These intricacies of history make it invidious to talk of the former state as if it were a unity, which is how both Dulat and Durrani talk. And if it is care for Kashmiris that is the criterion, Durrani emerges as the more humane person.

Both Durrani and Dulat blame their respective country’s media cacophony with Dulat calling the Indian media worse. Dulat says that the Kashmiris are ignored and repressed, although he thinks there are only a few dissidents. Durrani tacitly agrees, though he never says the state uses them, and that there are non-state actors who do attack India.

Both Masood Azhar and Hafiz Saeed are mentioned but Durrani says that the courts will decide the cases and, paradoxically enough, adds "if you prosecute Hafiz Saeed the first reaction will be: it’s on India’s behalf, you’re hounding him, he’s innocent, etc". In short, Durrani’s newfound liberalism deserts him and he takes more cognisance of the domestic cost than the humanitarian one or the risk of an Indian attack on Pakistan. Indeed, an Indian attack, he thinks can be "choreographed" which presumably means it will be on a target where many people are not killed and there is minimal damage to property. This will satisfy the Indian public and the media which is baying for blood, and business as usual will go on.

Both intelligence chiefs seem comfortable with this idea though it may lead to a nuclear holocaust which nobody takes seriously. Such is the stuff that disasters are made of and, incidentally, Durrani who calls Musharraf’s attack on the Kargil heights a stupid misadventure, calmly talks about these "choreographed attacks". Surprisingly, the notion doesn’t put him off. He does not say that misadventures like Pathankot and Uri and "choreographed" retaliatory strikes may be the end of South Asia as we know it.

Incidentally, Kasuri vehemently opposed such kind of retaliatory responses from India which keeps with the aim of preventing a nuclear disaster. Of course, the best way forward would be to prevent such attacks from both sides so that peace is not jeopardised, but neither Durrani nor Dulat say that.

While I am impressed by the spirit of the book and the resounding message of peace in the end, I am appalled at the way both spy chiefs talk about public opinion. Durrani, for instance, says that the public regarded Osama bin Laden as a hero so it was not wise to say that Pakistan had an arrangement with the Americans when they struck to take out bin Laden. Hence, the armed forces would rather confess to incompetency than complicity.

Read also: Illusions of controversy

Similarly, Dulat says if Kashmir goes, there will be riots against Muslims. Nobody mentions that it is those in power who must educate the public. There is so much propaganda against each other’s countries and against America and the West that it’s a wonder that ordinary people are still friendly towards foreigners in a personal capacity. And the states, deep or shallow, especially the institutions headed by the two main protagonists who spoke in this book are responsible for much of this ignorance and crass, visceral hatred.

The decision-makers are now captives of the public mood they created. And not once did anybody say that they will have to educate the public to desire peace. Of course the public cries out against books like this because they do not know that civilised conversation is possible, that different views must be heard and respected and that peace is something which we should all desire. But in the end I will congratulate both Durrani and Dulat for giving us the fruit of their interaction over years. It is a boon for historians.