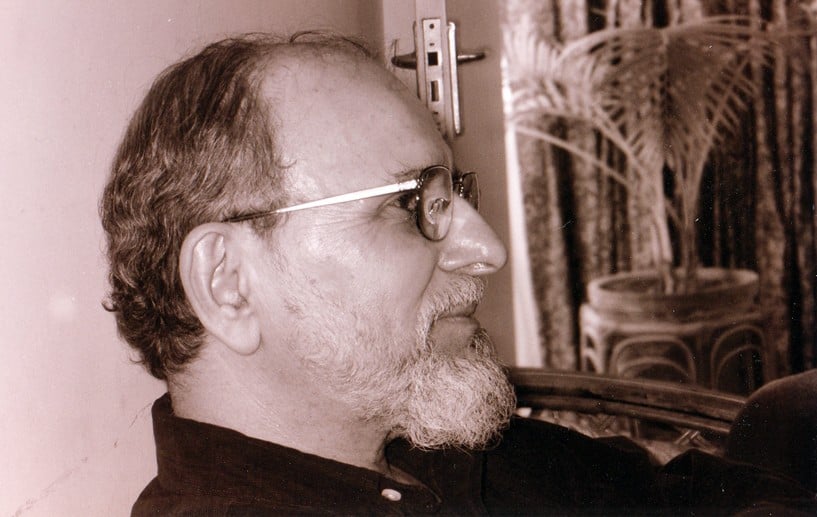

Being the leading translator of Urdu into English, Muhammad Umar Memon was an indefatigable promoter of the language

Garcia Marquez said in his pages that even vegetarians have been known to die from time to time. The same is true of sweet people on earth. Professor Umar Memon is such a person one wishes to have lived a long life. Those who are familiar with his dedication to Urdu and the amount of work he produced translating across Urdu and English while using his knowledge of European and Asian languages, Arabic being the most intimate, certainly would have liked to see him live at least a decade more. A person’s mortality, however, wins in the end.

Like many others, I too received the news of his untimely passing away at the age of 79 with shock and sadness. Those close to him knew his health had not been well, but just when it seemed under control, his creator pressed the wrong button on the remote control. That’s always the brief story of life.

Being the leading translator of Urdu into English, he enjoyed close friendships with several Urdu writers. He treated people as if they were his nieces and nephews such as the Urdu poet Riyaz Latif, who referred to the old man as mamoo. There was a time when Umar sahab and I spoke frequently, and I enjoyed hearing his pleasure and displeasure regarding certain writers. He spoke about things he liked or disliked with honesty and had no problem being straight, even curt, with me several times, whether on phone or in person.

He was always fond of sharing his latest translations. He was an indefatigable promoter of the Urdu language. I was fortunate enough to have been led by him to his office situated in the basement of his small but lovely house, with a nice garden in the back which his wife tended to passionately. With books and papers and yellow stickers everywhere, two or three computer screens seemed to always be on, where his work in progress beckoned him.

There were things which pleased him deeply such as the discovery of a new writer or a translator. He would often email me the attachment of a book’s cover, his joy boundless as he considered such efforts of love a non-monetary compensation of his hard work. He was very happy with some of the covers Penguin India did for his translations such as the one for Naiyer Masud’s The Occult. His other favourite was the cover of Essence of Camphor done by Katha, India.

But there were things which irked, or hurt, him as well. He felt very disappointed when a Karachi-based publisher rejected his translation of Shimon Ballas’ controversial classic Outcast, dealing with an Iraqi Jew who converts to Islam in the early part of the 20th century. He was equally distressed when a Lahore-based publisher, published The Tale of the Old Fisherman: Contemporary Urdu Short Stories without his permission which had already been published by an American publisher, Three Continents Press.

He was equally puzzled, even hurt, when the reissue of Intizar Husain’s Basti was published by The New York Review of Books, his original introduction replaced by someone else’s who had played no role in introducing Intizar Husain to the international audience. Still, after the moments of bitterness passed, he didn’t hold on to grudges and spoke with affection and admiration for writers he respected. They were like his brothers and sisters and throughout his academic career, he would seek out promising, energetic, capable translators who could be part of his crusade to share the world of Urdu fiction with the English reading world. I was one of them and that’s why I consider him my mentor. The lessons about attention, patience, and rigour which I learned from him, are the ones I apply when I write my own work.

Once standing before his several computer screens with texts in Urdu and English staring at us, he talked about what translating a text meant to him. He added that he’d waited and pondered for two to three days over a single word or a sentence several times. I might have mentioned in a different article that Professor Memon once told me, realising how little time I had for translations, that in the end one will be known, generally speaking, for his or her own work. It was his way of setting me free. Since then I have dedicated much more time to my own writing. This brings me to the point that Umar Memon is that rare selfless human being who actually gave up his own writing. His first and only book of short stories Tareek Gali: Muntakhib Afsane was published in 1989 by Sang-e Meel Publications. He could’ve easily taken some time off to work on his own fiction but chose not to.

It gave him tremendous pleasure when Naiyer Masud, an author Memon held in high esteem, wrote to him after winning India’s most prestigious award that it was due to him and his coterie of translators that such a recognition of his talent had been recognised. The same is true with regards to another great of modern Urdu fiction, Intizar Husain. If it weren’t for the translations of Intizar Husain which Professor Memon undertook, international acclaim for Husain might have been compromised.

He was also a generous person, be it affection, advice, a book or two, or friends. He connected me to several people I respect and love. As I said earlier, he loved to share stories about other literati of the Urdu world. Having spoken to him countless times, there are three names that come to mind now which I think he felt special fondness for, for one reason or another: Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, Naiyer Masud, and Ikramullah. He respected Ajmal Kamal’s faithfulness to Aaj, the finest Urdu literary magazine.

My last encounter with him was via email where he complained that I never reviewed his books. I wanted to clarify that I normally review fiction, not translations, preferably modern Punjabi prose for political reasons - but I couldn’t bring myself to say no. So I asked for a few titles, one of which I reviewed in these very pages, the translation of two French novellas by Francois Sagan into Urdu. I kept waiting for his email along with his reaction to the things he might not have agreed, but there was no email or phone call. I don’t even know if he read the review as I never asked due to my nervousness and now I regret not asking.

Read also: Remembering an ‘outsider’

As I write these lines as a way to consoling my heart, I realise that he might have been very sick on and off. He would’ve loved to receive a call from one of his admirers. Born in India, he was 15 when he moved to Pakistan and left for the US 10 years later, where after finishing his education at Harvard and then UCLA, he found love, raised a family, and called Madison his permanent home. But he was really a citizen of a language called Urdu and as his soul ascends upward, he’s got that language’s passport in his heart.