A progressive magazine that was shut down for raising an intellectually strong voice in favour of the marginalised

To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize - Voltaire

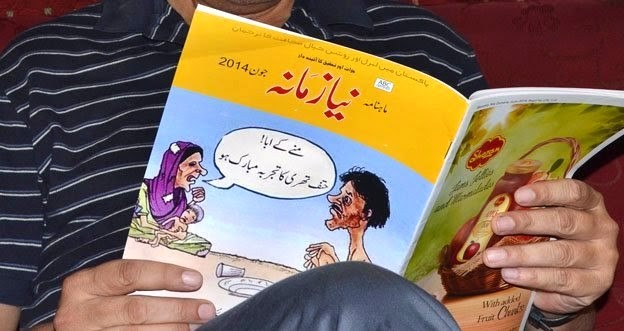

At the turn of this century, a progressive journalist Mohammad Shoaib Adil launched an exceptionally unflinching Urdu monthly Nia Zamana in Lahore and unbelievably sustained it for 14 years, with distinct quality contents daringly challenging the murder of truth in the popular mediated spaces, and the tyrannies of militancy and majoritarian reason in Pakistan.

In the face of an extremely tough time given by the over-increasing state repression, the decline of left, the rapidly-growing militarisation and Islamisation of society, and the coming of the age of corporate media, Nia Zamana continued to meet the characteristics of a radical publication -- unbeknownst to many, it was the Ayub’s regime that coercively started the policy of diminishing the tradition of alternative press in Pakistan and then the Zia’s regime completely destroyed even the remnants of it.

As any radical publication is supposed to be, Nia Zamana stood in need of introducing different analytical frameworks on political questions, attempting at deconstructing the official history, taking in a non-conformist way some taboo subjects like sex education and reflecting upon the importance of fine arts in the development of the society, prioritising as how could it broaden the visions of its readers on issues of society, politics, state, religion and history through its daring and conscientious editorials, reports and opinions. It tried to help people find better alternatives or bring changes in established political, social and intellectual systems.

By regularly carrying the voices of the subordinate classes as the most genuine ones of the country and by remaining open to views from multiple quarters of the society, Nia Zamana provided a sort of space of contestation for creative and critical debates on ideas and possibilities of emancipation, peace and prosperity in Pakistan and the South Asian region.

Throughout its journey, the magazine, however, seemed as principally interested in bringing out the write-ups of the subordinates instead of the intellectual elites. In other words, it was interested in finding and narrating the untold, unheard and unpopular stories of the masses rather than requesting the popular names to join the list of contributors.

More importantly, Nia Zamana was distinctively the only publication in the heart of Punjab, Lahore, that raised an intellectually strong voice in favour of the marginalised. It remained radically critical of the anti-federation policies of Punjabi political and military elites and by doing so it earned an overwhelming popularity and a wider circulation in smaller provinces.

I remember how Baloch, Pashtun and Hazara political workers, especially young activists and students, were eagerly waiting for the arrival of the new issue of Nia Zamana in Quetta.

One of the most striking distinctions of the magazine was, however, its thorough investigative reporting on the development of Jihadi politics, free mobility of the banned militant organisations, emergence of Punjabi Taliban and the systematic cleansing of vulnerable religious minority groups in Punjab.

Nia Zamana regularly raised the issue of organised violence acting on specific political groups in peripheral areas and fearlessly disclosed the identity of the ‘unknown’ involved in incidents of target killing, enforced disappearances and abductions for ransom.

It brought out, for instance, a special edition on the assassination of Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti, and warned the state of dire consequences for this unprecedented cruelty in the history of its coercive relationship with the Baloch nation.

Similarly, its special reporting on the murder of Benazir Bhutto, its consideration of the murder of Salman Taseer as a murder of sanity, and its stand on the murder of Rashid Rehman, a human rights lawyer who was killed for defending a professor accused of blasphemy charges, were evidences of its progressive and radical credentials. The only way out it principally suggested was that politics belongs to people and only they have the right to do it. Not only a secular, but a truly democratic state could be the representative of people.

Through its straightforward editorials and bold opinion pieces, it continuously opposed the state’s flawed policies towards Afghanistan and India and its bloody games played out in the Pashtun homeland.

Nevertheless, Nia Zamana was extremely sceptical of the high expectations attached with the Lawyer Movement, the struggle that emerged for the restoration of judiciary in 2007 and continued till 2009. The way judicial activism started rapidly dominating the political scene and interfering in the business of the elected institution, it was easy to realise that the judiciary would soon acquire a higher position in the ruling historic bloc in Pakistan and would squeeze the democratic transition in the favour of the powers that be.

Then, the judiciary got ‘independence’ and an elected government completed its term and transferred the power to another elected government for the first time in the history.

Nia Zamana had to stop its printing after its June 2014 issue. On June 11, 2014, the 14-year regular publication of the only representative magazine of the subordinate classes of Pakistan came to an end when a group of religious fanatics accompanied by police attacked the magazine office in Lahore and accused the editor, Mohammad Shoaib Adil, of blasphemy charges for publishing the autobiography of a Lahore High Court Judge who was an Ahmadi by faith.

Shoaib was sure that the main target of making a controversy out of a book, which was published in 2007, was to shut down Nia Zamana. Finally, he concluded from all his reading of the situation that he could no more live in Pakistan. So, he left.

Despite living a very miserable life in America, Shoaib Adil launched an online version of Nia Zamana in 2015 that is updated on daily basis and underscores, to some extent, the continuity of the tradition of the magazine’s hard copy. But, that web version too is inaccessible in Pakistan for the last couple of weeks.

Nia Zamana has long ago deconstructed the myth of free media and has fearlessly named the institution that controlled it, that we have seen repeatedly proven. So is the fate of similar materials in other publications, even the leading English dailies, in Pakistan. We all know who is afraid of Nia Zamana (New Age) and the power of dissent in this land of the pure.