The Army Museum showcases Pakistan’s history through a fetching interplay between design and tech

The Army Museum, inaugurated in September 2017, is quite unlike the only museum I knew growing up: the creaky Lahore Museum whose dull displays led many a Lahori child to forever equate the word museum with boredom.

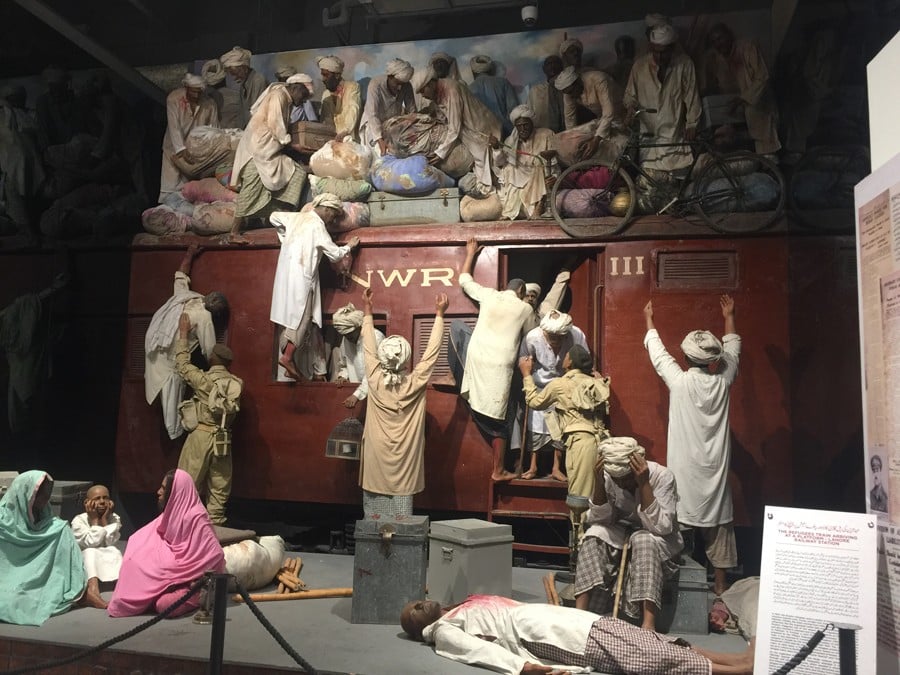

The Army Museum, unlike its colonial predecessor, is an immersive facility that showcases Pakistan’s history through a fetching interplay between design and tech. Its most exciting aspect is that much like the institution it represents, it doesn’t just stick to its own mandate, but goes much beyond it. This isn’t just a lifeless space displaying defunct helicopters and tanks, but a cutting-edge facility, ambitious and wide in its design and scope, taking in the grand sweep from partition to wars, from terrorism to culture; comfortably claiming all of Pakistan’s history and progress as its own.

As a citizen of Pakistan, if there is one thing I can vouch for, it is that the best land and infrastructure in the country belongs to the army. This museum is no exception. The money spent on it speaks for itself; in the clean, majestic lines of the building’s façade, in its sprawling lawns and polished floors, the awe-inspiring sculptures of warring horses and elephants, Quaid-e-Azam, Fatima Jinnah and Army Generals -- the incontestable grandeur cannot be missed any way you turn.

The museum exhibits are divided into sections representing different aspects of the Pakistan Army. The first section is a series of wall panels inscribed with an exhaustive list of army men who have died fighting battles for the country since its inception. Coming face to face with wall upon wall carved with the names of thousands of young men who died prematurely is a sombre experience. In chronological order you can read these names, starting from 1947. Men died on the border every year, some years more so than others. 1965 has 16 panels; 1971, 39. The dead of Kargil fit on five panels, but there were some years, 2005 (6 panels) and 2009 (another 6 panels), whose body count left me baffled. What did all these sepoys and lance naiks die for? I wasn’t sure. All that stared at me were their names, one on top of the other; foot soldiers lost in battles I couldn’t recall.

An instrumental version of ‘Ae Rah-e-Haq ke Shaheedo’ played soulfully in the background. I sang the lyrics in my head…‘Watan ki beityaan maaen salaam kehti hayn,’ hoping they find some solace from the comforting rhetoric of shahadat (martyrdom), and entered the next section comprising bronze busts of Pakistan’s chiefs of army staff, most of whom are fortunately alive and healthy. The inscriptions next to their names detailed their professional achievements, but General Ayub, General Zia and General Musharraf’s inscriptions failed to mention their contributions to Pakistan’s politics. Odd oversight.

Another section focused on Pakistan’s history. It was fun to read about the Assyrrian Queen Semiramis’s "invasion of Pakistan" in 800 BC and Alexander’s "invasion of Pakistan" in 327 BC. This section also had remarkably realistic sculptures of Quaid-e-Azam, Fatima Jinnah, and Lady and Lord Mountbatten, which formed the centre of attention of most children visiting the museum. These sculptures, many of them so striking you could mistake them for actual people, made me want to know who had shaped them with such deft realism, but I couldn’t find artists’ names anywhere.

Even the paintings of ancient sites of the subcontinent (nay Pakistan), like Mehergarh and Harappa, were credited to a generic "musavvir ki aankh se." I guess the curators felt there wasn’t much need for artists’ names in a military museum.

There were sections detailing the history of the 1965 and 1971 wars, teaching the younger generation about the Pakistan army’s complete annihilation of its easterly neighbour’s army in both these wars. It also spoke of how its nefarious designs have always been well-foiled by the army of Islam.

But the museum doesn’t just celebrate the mainstream; it also goes on to celebrate the military’s diversity. There is a wall with pictures of Pakistan army’s female staff, although these portraits aren’t accompanied by names. I guess it is enough for women to have found space in the Pakistan army. What’s in a name?

Pakistan army martyrs belonging to religious minorities have a dedicated wall of portraits too. By virtue of being men, they also find themselves named.

There is a documentary area with a large fitted screen that was playing morale-boosting songs sponsored by the ISPR. Next to it is the section on "War Against Terror," an artfully done area with a metal detector gate that leads to a gallery of mirrors; a plaque above it reads "The Enemy Within" as you stare at yourself in the mirror. This area exits into the Rehabilitation section that details the army’s efforts in rejuvenating Pakistan from the aftermath of the war on terror. It gives them credit for not just their security endeavours but also the cultural and economic revitalization of the country. It ends with a huge portrait of Pakistan’s cricket team celebrating its T20 Champions Trophy win in London, indeed a milestone the Pakistan army can take credit for.

The Army Museum will surely be visited by an unprecedented number of Lahoris and visitors to the city, and they will go back hearts rekindled with the love of home and country.