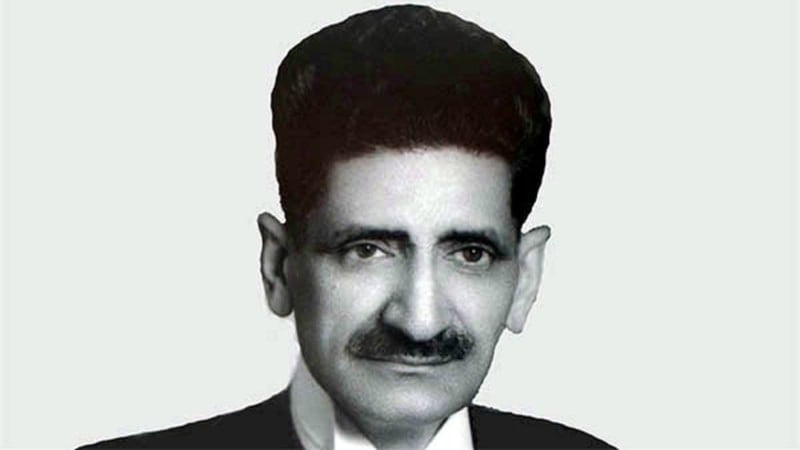

The speeches and writings of Justice Rustam Kiyani are as much as testament to his great oratory skills and charming wit, as they are a caustic critique of the world around him

Over the last several weeks, I have been readings the writings and speeches of Justice Muhammad Rustam (M.R.) Kiyani, who was the Chief Justice of the West Pakistan High Court from 1958 to 1962. Justice Kiyani was a man par excellence: he was a sharp jurist, a man of great wit, and a keen observer of the world around him. His speeches are as much as testament to his great oratory skills and charming wit, as they are a caustic critique of the world around him.

Justice Kiyani was never overtly political, but used allegory, stories and other references to underscore the importance of the rule of law, fundamental rights, and, quite simply, the dignity of every human being.

Justice Kiyani was a vociferous supporter of the writ jurisdiction of the superior courts. The writs of mandamus, certiorari, quo warranto, habeas corpus, and prohibition, were to Justice Kiyani essential for the protection of the rights of the people. In one of his speeches, Justice Kiyani noted: "what we want is that everybody should have a feeling of security, a feeling that nothing will be done to him in bad faith or that capriciously or arbitrarily." He emphasized that writs were perhaps the surest way to ensure rights. He said: "…writ jurisdiction brings to a benighted morality the light that never was on sea or land. God is in His Heaven and all’s right with the world -- God was in His Heaven even before writ jurisdiction, but all wasn’t right with the world."

However, Justice Kiyani was also cognizant that writs should not simply be used by the courts as a stick against the government, and be employed to achieve cheap publicity. He noted: "It is unfortunate that whatever decision we take against the government makes us popular, and it is therefore necessary that we should not seek cheap popularity…." Justice Kiyani knew that often writs bring the government and the judiciary into conflict, but that it should not be seen as an adversarial match but a joint effort to ensure the rights of citizens.

Despite the fact that during this tenure martial law was in full force, Justice Kiyani did not shy away from criticising its imposition. Speaking at an event he noted that he was in his native village when he heard about the dismissal of the government and the imposition of martial law, and lamented ‘misfortunes do not come alone, but in battalions; and in this case it was a whole Army!’ The news greatly affected Justice Kiyani and he said that he felt as if he had dropped ‘a thousand feet in an air pocket.’ Therefore, he resolved to be even more assertive in the protection of rights, especially since writs had been curtailed under the martial law ordinance.

Justice Kiyani did not shy away from satirically commenting on martial law authorities. Talking about General Azam, he once noted: "…I saw General Azam being carried over the shoulders of cameramen; but what helps him most is his deaf ear, which he turns to you when he does not wish to hear, and which carries him forward instinctively." Similarly, he did not hesitate in reminding the martial law authorities that their main task was to defend the borders and not to run the country. He stated: "…lest our sons and nephews should lapse into a life of ease, and forget their professional duty, which is to defend the country, this is an additional reason why we should hasten back to normal life."

Justice Kiyani never minced his words, and never lost an opportunity to remind the army that it must go back into the barracks. Even though he was an ardent admirer of the legal acumen of Justice Munir, his senior colleague and also Chief Justice of Pakistan, with whom he co-authored the famous Munir-Kiyani Report of 1953, he still criticised the legalisation of martial law under the doctrine of necessity. In his quintessential witty style, Justice Kiyani exclaimed: "An efficient Army, unsophisticated by the doctrine of civil necessity, is the first need of a country like Pakistan…."

The speeches of Justice Kiyani are also a very important and critical commentary on the state of the law profession and the judiciary. He often spoke on themes related to corruption in the system, the conduct of lawyers, and matters connecting the bar and the bench. For example, he cautioned judges against not hearing a case on its appointed day, "for it is better that a case should lie in cold storage than the parties and their witnesses should be told at the end of a hot day that their case could not be taken up for want of time and that they should go back fifty or a hundred miles."

Justice Kiyani also lamented the decline in the quality of lawyers and advised senior ones to "associate with them junior lawyers of promise, who work hard, put them on the track of a case, but attend to it finally themselves." He also often reminded the lawyers that they are "officers of the court’ and therefore their work does not end ‘with securing an acquittal or having a case dismissed."

Justice Kiyani also had a keen eye on societal development and several of his speeches are peppered with sharp commentaries on the decay of society. For example, when once speaking of his birthday on the 18th of October, he noted: "…I am not at all sure that I was born exactly on the eighteenth of October, because those I saw existing already at the time of my birth, sucking and toddling, were born quite a year or two afterwards, if the records of the government are true." This was of course a reference to the common practice in Pakistan where parents, in hope of some future benefit in terms of jobs, officially record their children a few years younger.

Again, noting that corruption had increased dramatically since partition he narrated a story: "I have an agent who told me a story about his brother, who is an army contractor. He had to make a small bridge for which, among other things, five hundred bags of cement had been sanctioned. Normally, the contractor before the Partition laid apart two hundred and fifty bags. But this bridge was made after the partition, and my agent says that his brother used only thirty bags on the bridge and appropriated the balance of four hundred and seventy bags to his own use.’ Justice Kiyani often employed such anecdotes to illustrate increasing corruption and its acceptance in society.

Read also: Remembering Justice Kayani

Justice Kiyani was certainly a rare breed. His charm, intelligent wit, and caustic commentary on all affairs, legal and sundry, are a critical testament of their time, and even relevant today. However, Justice Kiyani was also very funny, and his speeches have several light moments, which put people at ease and yet made a significant point. In one such speech, Justice Kiyani, while commenting on the religious precept to ‘eat and drink’ said: "…this should be an effective answer to prohibitionists, because if the word "drink" means drink as much as you can, then it includes something more than water, for you cannot drink more than a glass of water and a word so full of meaning as drink so simple in expression, so superlative in dignity, could surely not have been used to sanction a mere glass of water." A judge may indeed laugh too.