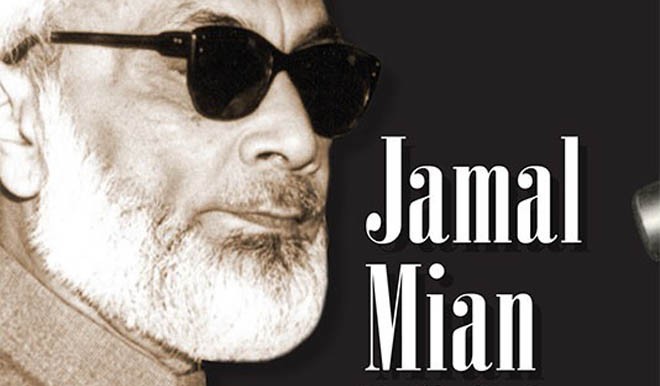

A biography that gives a detailed account of the intellectual and moral heritage of Jamal Mian

Professor Francis Robinson’s scholarly work on the Farangi Mahall Islamic scholars entitled The Ulema of farangi Mahall and Islamic Culture in South Asia (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2001 and Lahore: Ferozsons, 2002) is the only academic study of this famous Islamic seminary and the scholars associated with it. In this study, Robinson gave an account of the contribution of Abdul Bari of Farangi Mahall to the Khilafat Movement in particular and the freedom movement of India in general.

It was because of this writing on Abdul Bari that his son, Jamal Mian, met Robinson in 1976. By this time, Robinson’s doctoral thesis at Cambridge had been published as a book entitled Separatism Among Indian Muslims: the Politics of the United Provinces’ Muslims 1860-1923 (Cambridge University Press, 1974). Jamal Mian, being a voracious reader, had read it and appreciated the fact that a British academic had given such detailed attention to his father. So Jamal Mian met the author in London and, after correcting a few errors in the book, the two ‘continued to talk for hours’ (p. xiv) with Jamal Mian offering his archives to the researcher for further research. This book is one of the products of this generous offer and, of course, a testimony to the hard, painstaking work which is a hallmark of all writings of Francis Robinson.

The biography, Jamal Mian: the Life of Maulana Jamaluddin Abdul Wahab of Farangi Mahall, 1919-2012, has fourteen chapters, two appendices, a bibliography and an index. It is carefully researched with every fact being corroborated by archival material as well as secondary sources from the relevant period. The first chapter starts with the young Jamal Mian -- he was less than eighteen which was the minimum age for Muslim League membership -- delivering a speech in a Muslim League session. Although so young, as MA Jinnah observed when he stood up to speak, he came from the famous Farangi Mahall family which was a name to conjure with in the religious as well as the political world of Indian Muslims in the pre-partition years of British India.

The next chapter, appropriately enough, is about this family. Here Robinson gives a detailed yet succinct account of the tradition of Farangi Mahall which is the intellectual and moral heritage, the cultural capital as it were, of Jamal Mian. This heritage is important as it placed Jamal Mian in the elite circles of Indian Muslim and later Pakistani society. He may be struggling financially as he was at times, but he still had access to presidents, prime ministers, ministers and highly placed bureaucrats and industrialists. This was made possible of course by his personal contributions but it was who he was which made these contributions possible in the first place. The chapter is important for understanding not only the life of the subject of this biography but also the worldview of the society he came from.

Jamal Mian was primarily a cleric. The Farangi Mahall seminary was, after all, one of the famous madrassahs, an institution for Islamic learning and training of the clergy, in India. The fame of this seminary rests, among other things, on one major achievement i.e the curriculum Dars-e-Nizami which is common in slightly amended forms all over South Asia in both Sunni and Shia madrassahs. This course of studies was made by an ancestor of Jamal Mian called Mulla Nizamuddin.

But, besides Islamic studies, Jamal Mian’s family was well versed in the intellectual traditions of the gentlemanly class of the United Provinces (the sharif culture). Thus appreciation of poetry, especially the Urdu ghazal, played a major part in the making of an educated sharif person. Thus his library contained the poetic works of Ghalib and the famous masnawi of Rumi besides other classics (p. 344).

Other values of this gentlemanly culture often played a role in the political lives of Jamal Mian and his contemporaries. For instance, political rivals would very graciously help each other even to the extent of providing a vehicle full of fuel for the rival to campaign against one. They would have meals together and be polite and friendly with each other outside the political arena. Political rivalry did not translate into personal enmity or bad manners.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Jamal Mian is that, although he was an Islamic scholar and heir to a legacy of Islamic scholarship going back to more than two hundred years, he wanted Pakistan to be a liberal democratic state rather than a Muslim or Islamic state. He pointed out in Jinnah’s presence that "Islamic History had witnessed a number of bad rulers who in the name of Islam had committed all sorts of sins and cruelties" and thus wanted the term ‘Muslim State’ dropped out of the resolution about the birth of Pakistan (p. 208). Jamal Mian’s amendment was either put to the vote and lost, which is what he himself claimed, or he withdrew it which is what the record made by Pirzada indicates.

He also opposed Liaquat Ali Khan’s ‘Objectives Resolution’ on the grounds that this attempt to make Pakistan an Islamic state would ‘be the source of chaos’ (p. 362). This too was turned down. However, Jamal Mian remained an advocate of democracy and an opponent of efforts to turn Pakistan into an Islamic state all his life. He was also one of the few Islamic scholars who disapproved of the constitutional changes which made the Ahmadiya community a religious minority in 1974. His view, which he expressed in his diary, was that this would threaten ‘Pakistani unity as a nation’ (p. 325).

He was also original in his approach towards India. While others advocated a strong line against India Jamal Mian thought it was necessary to make friends with that country (p. 236). His personal relations with Indians in high position, including Nehru himself, were always good. Indeed, when he was still an Indian citizen in 1950 he stayed on Hajj with Pakistan’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia while as a Pakistani citizen in 1958, he stayed with the Indian ambassador. In short, he was one of the few religious figures whose ideas and behaviour put him in the category of liberal leftist Pakistanis who were almost always educated on secular Western lines and had no specialised knowledge about religion.

Possibly because of his personal relations with people in power -- Iskander Mirza, Ayub Khan, senior bureaucrats, industrialists like the Isphahanis etc -- Jamal Mian was inclined to support people in power. For instance, he supported Ayub Khan rather than Fatima Jinnah in the 1965 elections. However, this support was based on personal relations rather than on any clear understanding of Ayub’s policies. Indeed, although he kept diaries, Jamal Mian does not allude to policies which created problems for Pakistan. Thus he left the events of 1971 entirely untouched.

According to Robinson "we must assume that he was too depressed to write" (p. 306) but a less charitable view could be that he was an establishment figure who tacitly supported policies which led to the creation of Bangladesh and was reluctant to confess that those policies were wrong to begin with. After all, the architects of these policies, including Ayub Khan himself, had obliged Jamal Mian in a personal capacity and even made him the owner of a mill which ensured that he would not live in penury in his old age. Chapter 13, on his life in Karachi, gives the details of this life and one notes that it is an upper middle-class life such as Jamal Mian had always enjoyed.

Francis Robinson sums up Jamal Mian’s life very well in the last few pages of his biography. He combined the most refined cultural traditions of the Indian Islamic and the Western civilisation with a personality which wanted peace and harmony. The author uses a vast archive of sources, mostly from the archives of Jamal Mian’s family, to write this sympathetic biography. On this point, however, I beg to differ from the author. While it is necessary to be sympathetic with the subject of one’s biographical writing in order to enter his or her world and comprehend it fully, I feel that it is also necessary to point out in what ways the subject fell short of universal moral values.

In Jamal Mian’s case, I feel that he did not oppose people in power such as Ghulam Mohammad, Iskander Mirza, Ayub Khan or Yahya Khan even when he was still active in the political field. He did not also resist the changes made by Zia ul Haq in Pakistani society in the name of Islam though here too his contribution as a scholar of Islam could have been useful at least for history though it would not have made any practical difference. In short, Jamal Mian was pro-establishment, and this should have been explicitly pointed out in this biography.

Having said this, I should hasten to conclude that this biography of Jamal Mian is a much-needed contribution to the field of South Asian history. Francis Robinson was already the major scholar in this field -- and especially on Farangi Mahall -- and this book advances his work in this area. The book is a landmark and should be of interest for all those who are interested in Islam in South Asia. It is written in such accessible language that it can be enjoyed by lay readers who will certainly profit from it.

Jamal Mian The Life of Maulana Jamaluddin Abdul Wahab of Farangi Mahall, 1919-2012 Author: Francis Robinson Publisher: Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2017 Pages: 429 Price: PKR 1250