Lawrence brothers became legends when they restored law and order and provided quick and cheap justice to people in the Punjab

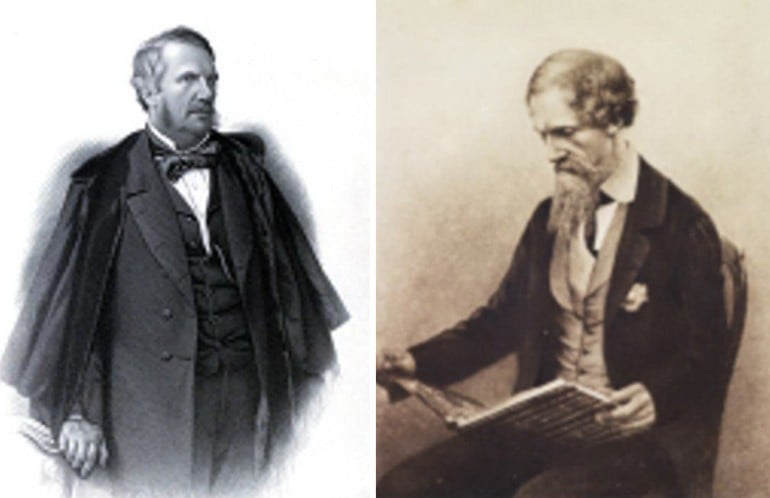

The annexation of the Punjab brought about a rapid and radical change in the administration of the territory. From the haphazard administration of the late Sikh Court, the last British Resident to the Court of Lahore, Sir Henry Lawrence became the president of the new Board of Administration of the Punjab with specific responsibilities for foreign affairs and relations with the sardars.

Sir Henry was vehemently against the annexation, and even tendered in his resignation, but Lord Dalhousie convinced him to stay on "if only for the special reason that it would ensure his having the best opportunity for effecting his great object -- the fair and even indulgent consideration of the vanquished." Sir Henry was joined by his brother -- John Lawrence -- who would later rise to be Viceroy and Governor General of India, as member in charge of the settlement of land and fiscal matters, and C.G. Mansel, as the member for the administration of justice and the police, soon to be replaced by the indefatigable Sir Robert Montgomery. These three men then became "the heart, the backbone, and the arm of the Punjab’s body-politic".

The Board quickly reorganised the province under them, with the help of the ‘best men in India,’ as the Viceroy Lord Dalhousie had promised. Out of the 56 covenanted officers sent to the Punjab 29 were from the army and rest civilians, creating a mix of military and civil rule -- again a first in India. The country was divided into seven divisions each headed by a commissioner, who in turn presided over twenty-five districts which were governed by deputy commissioners and assistant commissioners.

The work and life of the Lawrence brothers in the Punjab quickly became a matter of legend. The Irish and Scots mix Lawrences would be seen galloping throughout the Punjab, listening to the pleas of the people, adjudicating disputes, settling revenue claims, and pacifying the countryside. Sometimes the formidable duo would travel thirty or forty miles a day and assess first hand the conditions of this vast province.

But both brothers had different outlooks for the Punjab. While the elder, Sir Henry’s sympathies ‘were all on the side of the old aristocracy,’ the younger John ‘was equally zealous on behalf of the masses who lived by the labour of their own hands and brains.’ John, who succeeded his brother as the Chief Commissioner of the Punjab after the dissolution of the Board of Administration in 1853, was very popular among the people earning him the title of ‘the saviour of the Punjab.’ A contemporary, Charles Raikes, once wrote about the reasons for his popularity: "First, he was at all times and in all places, even in his bedroom, accessible to the people of his district. He loved his joke with the sturdy farmers, his chat with the city bankers, his argument with the native gentry. When out with his dogs and gun he had no end of questions to ask every man he met. After a gallop across country, he would rest on a charpoy and hold an informal levee of all the village folk, from headman to barber. ‘Jan Larens sab Jaanta," the people said (John Lawrence knows everything). The Lawrences had indeed begun a transformation of the Punjab!

The restoration of law and order and the creation of a formal system of justice was one of the foremost preoccupations of the British after annexation. There were people to be disarmed and settled, gangs and robbery to be dismantled, social evils to be countered, and a fair, equitable and expedient system of justice established. The government therefore addressed these issues one by one. First female infanticide was tackled which was very prevalent among the rich Khatri and Bedi castes. Their reason for killing their girl child was apparently ‘pride of birth and pride of purse,’ and some even claimed that since Guru Nanak came from these castes, having a female in the household would diminish their rank.

The government quickly and firmly put down this vice and ensured that every perpetrator of his heinous act was brought to justice. During the administration of the Board highway robbery was also countenanced through the creation of a network of roads and regular patrols by the mounted police. Even the dreaded crime of Thuggee was brought under control fairly quickly so much so that by 1853 the Thuggee offices had to be shut down. Thus during the short tenure of the Board of Administration, major crime had been brought under considerable control in the Punjab.

The British were also the first ones to introduce the modern concept of police and jails in the Punjab. During Sikh rule a fine or mutilation was the usual sentence, and there was no concept of a jail. The Board built a network of jails throughout the province so that criminals could be kept under confinement and, hopefully, reformed. There was a central jail in Lahore, three provincial jails in Rawalpindi, Multan and Ambala and twenty-one in each of the other districts. Inmates at these jails were trained in the industrial arts and even a lithographic press was established at the Amritsar jail. The inmates also grew their own vegetables, made their own clothes and even learnt how to read and write. The aim was that "having acquired a useful trade, learnt to read and write and received the elements of practical knowledge," the prisoners might not return to their olden ways but become useful members of the society.

The Board also established a police network with 228 police jurisdictions throughout the province, with an officer, a subordinate officer and about thirty policemen in each jurisdiction. The police was divided into two parts: the preventive police with a military section and the detective police with a civilian organisation. The preventive police was further divided into the cavalry and the infantry. The "infantry furnished guards for jails, treasuries, frontier posts and city gates, and escort for civil officers," while the cavalry "were posted in detachments in Civil Stations and at convenient places on the roads to serve as mounted police".

The dramatic change in the social and political landscape of the Punjab was such that the first administration report of the Punjab could boast: "So thoroughly has turbulence and sedition been laid asleep that no single riot has anywhere broken out. Nowhere has resistance been offered even to the meanest servant of the government. All violent crime has been repressed, all gangs of murderers and robbers have been broken up, and the ring-leaders brought to justice. In no part of India is now more perfect peace than in the territories lately annexed."

In the years before 1857, the administration of justice and the judiciary had made considerable progress in the Punjab. Since the Small Causes Courts performed about two-thirds of litigation in the province there was a special focus on them. The government ensured that not only were these courts properly supervised, monthly reports were complied which were then sent to Lahore to be scrutinised and commented upon by the higher authorities. "It is believed that many improvements in the working of the courts are traceable to this system of supervision", the third Administration Report of the province noted.

The British were also very keen that justice should be readily available and that litigants should not have to travel far to have access to courts. Hence, on average a litigant had to travel no more than fourteen miles in the sparsely populated districts and less than ten miles in the more populous ones. This aspect of bringing justice ‘near’ to the people proved really popular as it allowed for a cheaper, quicker and more accessible form of justice hitherto unavailable in the Punjab. Thus by the end of 1856 there were in addition to the Small Causes Court, 111 courts of the Deputy, Assistant and Extra Assistant Commissioners, aggregating to a total of 215 courts, which was roughly one court of justice for every 59,152 people.

In the first decade after the annexation litigation, both civil and criminal, actually increased in the Punjab, so much so that by the end of 1857, the government was even noting that "the people were bringing more and more cases before the courts, until the proportion of suits in the Punjab to the population exceeded that in any other part of the Bengal Presidency, perhaps even all of India." However, this was not mainly due to any perceptible rise in crime, but due to the fact that justice was now easily, speedily and cheaply available.

The building up of trust, the establishment of a formal system of justice, and the general level of peace in the society meant that the average Punjabi was now better poised to defend his/her rights. A gleeful administration report noted: "The more free a Punjabee feels himself, the less he will tolerate nuisances from his neighbour, the more ready he will be to hail his adversary before the Magistrate."

Read also: The British and rule of law in the Punjab-I

The manner in which the Punjab was pacified and the rule of law established was one of the main reasons why there was less enthusiasm in the Punjab to join the Revolt of 1857. After a decade of turmoil, the Punjab was now experiencing peace, organisation and rapid development -- all of which then contributed towards the Punjab eventually becoming one of the most loyal provinces to the British.