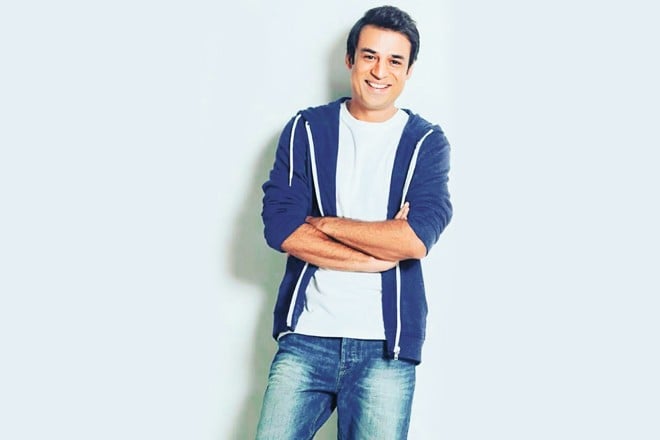

What started out as a small idea nearly two years ago has blossomed into a fully developed feature film that has caught everyone’s attention. And at the right time too. In the midst of Aurat Marches and #MeToo campaigns, Adnan Sarwar has recently launched the trailer of his upcoming marvel, Motorcycle Girl (MG), starring Sohai Ali Abro, Ali Kazmi and Sarmad Khoosat amongst others. Instep catches up with the filmmaker on his upcoming journey.

Instep: Was it a conscious decision to have a female-driven narrative, or were you gender blind when choosing your next project?

Adnan Sarwar (AS): I was working on some other script on an island in Thailand when I came across Zenith Irfan’s story, in which she was talking about her father’s dream to ride motorcycles. One can’t really predict a culture. At least I can’t. I can’t predict what the trends will be five years from now. We started making the film at a time where female empowerment wasn’t really such a hot topic. Somehow when we got to the stage of releasing the trailer, the timing was just right.

But the point of this film was to focus on the father-daughter bond. It’s not about promoting female empowerment, even though that’s a topic that I am very passionate about, having been raised by some very strong and incredible women.

Instep: What criticism, if any, have you heard from the audience regarding MG’s trailer?

AS: From complete rejection of the concept initially, to such universal acceptance, there’s a big difference. I think people put ideas in boxes. When I was trying to raise capital for the film in the beginning, I was told a lot of things. ‘No hero in the film, no songs? People come to the cinema to watch male heroes,’ I was told.

To raise the initial capital for our film, we had to sell off a bit of our company to get things going and to tell people that it is a good idea. Until and unless we create content and show it to people, how will we know if they will accept it or not.

There is no ‘hero’ in this film and there was no need in the story. All the men come and go. The story is about the journey of the girl. We have a great cast, people like Ali Kazmi and Sarmad Khoosat in the film, but they all have small scenes.

Instep: What was the budget for the film?

AS: It was under 3 crores. But this has only been made possible because of people like Jami. The cast that we have, the cinematographer, the production team - they all did this as a labour of love. Jami offered the equipment and the cinematographer. We didn’t spend too much on travel and accommodation. There was no lavish catering. Everyone sort of ate food from nearby dhabas while shooting for the film.

Still, the film doesn’t look like an indie film. The treatment is expensive looking and that’s because we had the equipment and the right technical team this time round.

Instep: Currently there is a debate amongst film critics that filmmakers should stick to making tried and tested commercial films and then go towards parallel cinema. What are your thoughts on this?

AS: I think we haven’t yet been able to define what commercial cinema is in Pakistan. Is it the appearance of item songs? I love item songs but we just can’t afford to shoot them. They just don’t look as nice. Our mehndi dances are better than some of the films’ performances you see nowadays.

For me, a commercial film is one in which the investment is secure, and it brings profit for the investors and producers. With that definition, was Shah a commercial success? Absolutely. I made that film with a microscopic budget and it still managed to make money. Am I looking at MG as a commercial film? Absolutely. Commercial cinema isn’t defined by a certain genre of film. Commercial films are those that are able to generate profit. There aren’t many films in Pakistan that can say that about themselves.

Instep: Did you take a lot of liberty with Zenith Irfan’s story?

AS: As I mentioned earlier, I was working on a script in Thailand when I saw Zenith’s video. I came back, got her life rights. In a nutshell, there is this girl, her father had a dream but before he is able to fulfill it, he passes away. His daughter then carries on with this dream. This is the basic DNA of the film. Everything else, we’ve built.

See, I’m never going to come and say "support Pakistani cinema" anymore. These words have been abused a lot these past few years. No, we have to create good content. Why should a family support your cinema by spending 5000 rupees on your film? Shouldn’t they go and donate to Edhi? Isn’t that a better cause? We have created such a film that when you go to watch it, you’ll walk out thinking that it was money well spent.

So to do that, we created a story around her motorcycle journey. I’ve made sure that the film is entertaining and not preachy. Unfortunately the film ends at a speech but that’s because Zenith ends up working as a motivational speaker in real life.

A lot of the dialogues that we have picked out are from her actual speeches. Some of the shots that we’ve recreated are real, like her iconic picture in the New York Times.

Instep: But have you used her real name in the film or have you created a fictional character based on her life?

AS: We’ve used her real name, but everyone calls her Chanda in real life. We have also talked about her blog going viral accidentally. And she’s a shy girl who reluctantly accepts her new position.

She shouldn’t become a celebrity because she rode a motorcycle. This is what is wrong with our society. What has she done? Nothing remarkable. Will she go on to do remarkable things in the future? Time will tell. I didn’t take that many liberties with her story so that it affects her future. There were certain ideas thrown at me. For instance, while riding her motorcycle, she stops at a village and drinks bhang there and then dances. We didn’t add something like that because it would have hurt her. We did script readings with her. We made sure that the script that we made, Zenith and her family were okay with it.

Instep: Perhaps this debate got stirred up because of the way Sanjay Leela Bhansali portrayed Allauddin Khilji in Padmavat. In your opinion, how much liberty can a filmmaker take with a real life story?

AS: When a film is released, and if it’s not a documentary, then it’s a work of fiction and then an artist has complete liberty. A person can use his personal, moral compass to keep himself in check. But if it’s declared a work of fiction, then it’s okay for an artist to create whatever story he wishes too.

An artist doesn’t owe anything to anyone. It’s not our responsibility to reform society. If you assume that your work will change society, then it’s bordering on megalomania. I’m not one of those artists who think that they’ll change the world.

Instep: But films are considered to have an almost hypnotic effect on people. In that case, does an artist hold some responsibility?

AS: If we start treating art like that, it’s dangerous territory. It starts to move towards propaganda and that is when the state steps in; we’ve seen this with the German film industry. If cinema is to have an impact, it should happen organically. If we start imposing our beliefs on cinema, then it veers between propaganda and censorship. Because then who will call the shots? A boardroom filled with old men with agendas.

Instep: What is then one supposed to do if there are, for instance, sexist films being made? Because people make the connection that crimes against women in India are rampant because their cinema is very sexist.

AS: It is said that society’s degradation is because of the media, but if you look at places where all sorts of weird, pornographic material is coming out, such as Scandinavia, then this argument falls flat. There are no crimes against women there. The stuff coming out from European countries is much worse than slightly kinky item numbers. Cinema isn’t responsible for fixing sexism. The problem with this side of the world is that society is sexist, that’s why such films are being made, not the other way around.

That change will come when a child is sent to school and taught the right values there. When you’re sexualizing children by making them aware of their differences at a young age or when boys are treated as golden boys in a household that has daughters as well, that is when you teach sexism.

The answer to fighting sexism isn’t censorship. It’s a change in curriculum and a change in our values. To fight domestic abuse and violence, stricter laws are the answer. Raising your boys better is the answer.