Highlighting the significance of English is often misconstrued as an attempt to impose the language and ‘belittle’ Urdu

Imagine a social media debate on the Big Bang Theory or Higgs boson particle! Even literate Pakistanis who are not well-versed in English would fail to contribute to it, not because of some fault of their own but because no resource is available in Urdu or in any of our regional languages on the topic, not unlike almost all other academic disciplines that shape the modern world.

The inability of the people to access knowledge from the original source has been manipulated by different interest groups over the years, so much so that the chasm between the worldview of Pakistanis who read and write in English (or any of the languages in which modern information is available) and of those who do not is now manifest in all possible areas of life, none more than social media.

As a consequence, a large number of Pakistanis who do not read and write in English are now literally dodging information, lest it poses a threat to their worldview!

A social media debate on Charles Darwin’s ‘Theory of Evolution,’ for example, would inevitably never move beyond the relationship between humans and monkeys; so much so that even an occasional attempt to pass on real information, say about fossil records and DNA, would be smartly thwarted by the ‘information-dodging’ group through the use of invective.

The void created by the dearth of information in Urdu and regional languages is filled (in most cases, overfilled) by the propaganda on social media and in the vernacular press that adequately satiates this group’s desire to know the ‘reality,’ as well as further reinforces the worldview it ascribes to.

Debating with members of this group, mostly young men and women, on social media is not easy; one, on account of their sheer numbers; and two, because of their sheer ignorance. They would rather base their arguments on the venom spewed by phony media anchors than what has been actually written or said; though admittedly, reading or research may not be their cup of tea, as reflected in their poorly drafted comments regardless of the language.

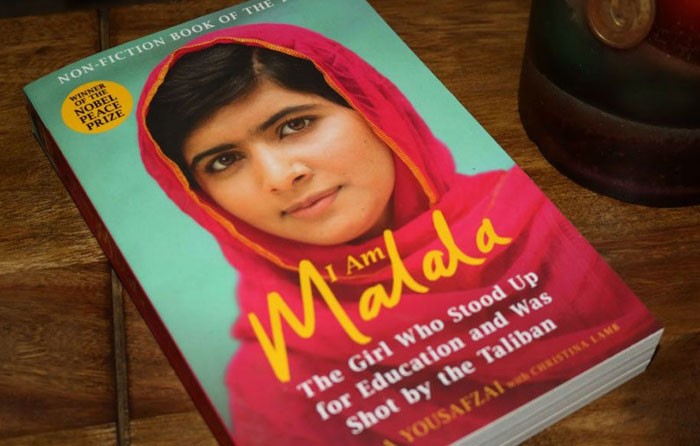

The response to I am Malala presents a classic case study in this regard. The information-dodging group pounced on the world’s youngest Nobel Laureate based on what was being said about her book by those who had not read it themselves or did not have the capacity to do so rather than what it actually said, again because the truth represented a sizable threat to its worldview. The demand for the ban on the sale of the book in Pakistan should also be viewed as part of information-dodging group’s strategy to nip the ‘evil’ in the bud.

Filling this information gap is difficult if not impossible because the supposed beneficiaries are wary of credible information from first-hand sources. No wonder then that highlighting the significance of English is often misconstrued as an attempt to impose the language and belittle Urdu; and comments like "English is not the language of our forefathers like yours" are not uncommon on social media.

Nationalism aside, why aren’t science subjects taught in Urdu at college/university level in Pakistan? Why one cannot take the CSS examinations in Urdu? Why are the interviews for the ISSB conducted in English? Even mildly put, this is nothing but an admission by the state that Urdu is incapable of catering to the needs of the modern era.

For the sake of comparison, in the neighbouring Indian state of Punjab, one can pursue a degree in hard sciences in Punjabi. In short, the message is loud and clear: the information gap is here to stay, as do the two opposing worldviews that currently define our nation.