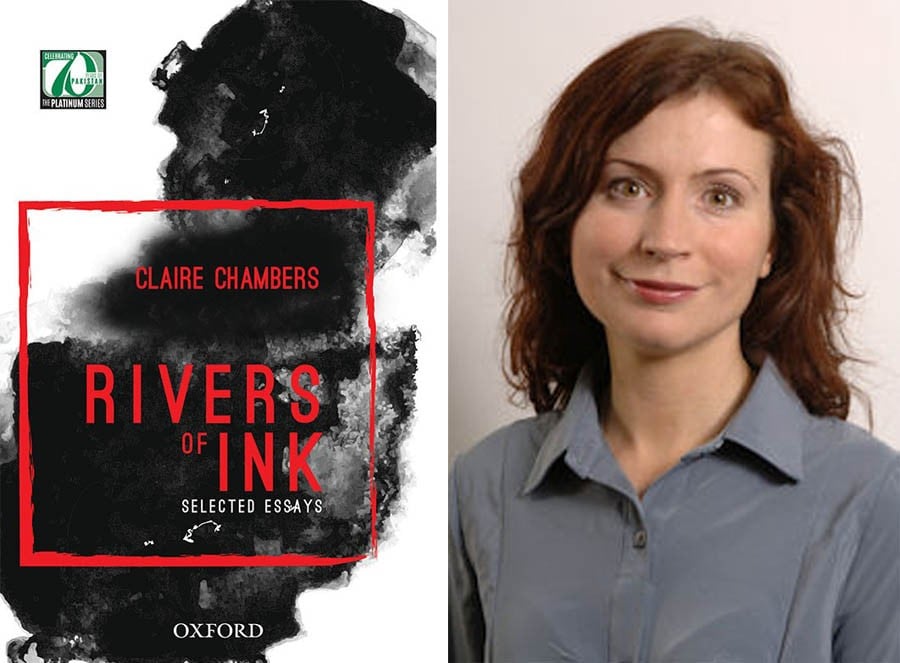

Claire Chambers’ recent collection of essays pays close attention to writings from South Asia. One wonders, towards whom is this call directed?

Claire Chambers, literary critic and professor of global literature at the University of York, first encountered Pakistan during her gap year between school and university in the early 1990s, when she taught at an elite college in Mardan. Its stuffy ostentation offended her hippie sensibilities, so she transferred to a public high school in Peshawar, where a third of the students were Afghan refugees, some so poor that three siblings would share a single pencil. "At least, that’s what they told this teenage English teacher from Yorkshire," she notes wryly in Rivers of Ink. "It may have been an excuse to get out of class and ‘Miss, brother; Miss, pencil’ became a common refrain even amongst kids I suspected didn’t have a sibling attending the high school."

Hosted by the headmaster ("a dry, twinkling Punjabi") and his family, with whom she surreptitiously binge-watched The Bold and The Beautiful in the evenings, she happened upon Midnight’s Children in Peshawar’s public library. "That book is all right, but his other book is very bad," the English-speaking Pakistanis around her felt compelled to comment. After reading Rushdie, she embarked upon what appears to be a lifelong love affair with South Asian literature.

Rivers of Ink, a collection of exactly three dozen pieces of writing, is the result of this infatuation, although it is in some respects even broader in scope. Chambers’ musings sprawl the gamut from broad reflections on global higher education and the global literary festival to a closer examination of such topics as postcolonial reworkings of Othello, the depiction of journalists in Pakistani Anglophone fiction, and the history and literature of the British curry house -- delightfully titled In Praise of the Chapaterati. Readers of Dawn may be familiar with some of these essays; Chambers writes a regular literary column for the newspaper, where some of these writings have earlier appeared.

Taken together, their overwhelming scope notwithstanding, the essays are intended as a call to pay closer attention to writings from South Asia, particularly Pakistan and its diaspora. One can’t help but wonder, towards whom is this call directed?

This is not a volume to be consumed in one sitting, but one particular section that lends itself to that sort of wholesale consumption is the regional examination of Pakistani fiction, with separate chapters for Kashmir, the provinces of Balochistan and Sindh, and the cities of Peshawar, Lahore, Rawalpindi and Islamabad (Karachi is, surprisingly, missing).

Chambers’ writing is most compelling when she weaves memoir into her literary criticism -- as in the Peshawar chapter -- or when she focuses on close textual analysis: she examines, for instance, how the ‘depressing greyness’ of the Balochistan landscape described in colonial writings is depicted far more sympathetically in Jamil Ahmad’s The Wandering Falcon: "There were subtle changes of colour in the blackness of the nights and the brightness of the days, and the vigourous colors of the tiny desert flowers hidden in the dusty bushes, and of the gliding snakes and scurrying lizards as they buried themselves in the sand."

One wishes such an analysis could be carried out across languages -- Chambers, understandably, limits herself to writings in English.

Reading Rivers of Ink, I was reminded, oddly, of The Possessed: Adventures with Russian Books and the People Who Read Them, Elif Batuman’s rapturous immersion into Russian literature. They are wholly dissimilar books, both in intent and effect, although I imagine Chambers and Batuman are on the same page, so to speak, as far as their approach to literature is concerned: "I stopped believing that ‘theory’ had the power to ruin literature for anyone, or that it was possible to compromise something you loved by studying it," wrote Batuman in The Possessed. "Was love really such a tenuous thing? Wasn’t the point of love that it made you want to learn more, to immerse yourself, to become possessed?"

Chambers’ love for South Asian literature is evident in the painstaking manner in which she teases out themes and patterns, and situates them within a broader postcolonial context, but it also made me yearn for another, different book: one that doesn’t concern itself with proving value, but tumbles head first into the cannon, heady with delight that is so infectious that you can’t help, senses tingling, tumble in yourself.