The post of Pakistan’s ambassador to the US calls for a combination of an astute diplomat and a skilled politician

The civilian government that followed General Pervez Musharraf’s long dismal rule brought a ray of hope to Pakistan. Right away, the PPP-led setup signalled to American diplomats that the bilateral relationship between the two countries was about to change.

The US media ruthlessly called US demarches to Pakistan in Musharraf’s last days as a "public dressing-down", and the forceful indication of the turning tide came from Asif Ali Zardari’s then top advisor, Husain Haqqani. "If I can use an American expression, there is a new sheriff in town," he announced, "Americans have realised that they have perhaps talked with one man for too long."

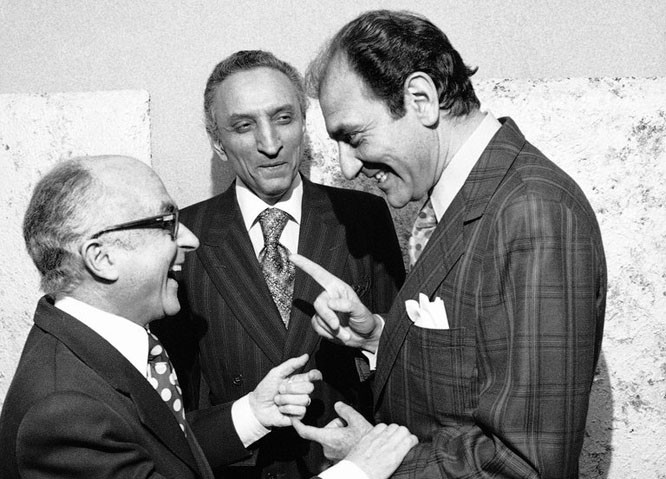

Haqqani was the Ambassador-designate to the United States (2008-2011), owing to his commitment to the party leadership, and his connections in the American political quarters. His familiarity with faces and tremendous outreach before he even assumed the position secured him praise from the US media. The Washington Post reported his appointment in an article titled, ‘Haqqani back in DC where everybody knows his name.’ The almost celebratory tone of the article acknowledged: "Most ambassadors gain real influence only after years of working in Washington’s corridors of power -- and often only with the help of expensive lobbying firms. But Husain Haqqani, the ambassador-designate from Pakistan, already knows almost everyone who counts."

The outgoing and incoming US administrations welcomed the change and announced to offer a five billion dollars civilian assistance package that otherwise came to be known as Kerry-Lugar-Berman bill. This was the only time in recent history when leaders of both countries strived for a fresh and friendly start.

On the day of President Barack Obama’s inauguration on January 20, 2009, the Financial Times included Haqqani’s name amongst a list of 50 people who were likely to influence the Obama administration most. Influence, he did.

The new sheriff, arguably, became the busiest foreign diplomat in town. He got busy giving interviews to various international media outlets around the clock, dealing with different arms of the US administration on a daily basis, and positioning Pakistan’s policy on a track that was not nose-diving; until his strength of knowing his way into the American system was treated as his weakness at home in Pakistan.

The Memogate scandal could have hit him personally, but for the country the lowest point was when the Obama-led White House unilaterally raided Abbottabad and killed Osama bin Laden. As ambassador, Haqqani used official diplomatic channels but also remained in direct contact with his political leadership at home for guidance and advice. So did his successor, Sherry Rehman (2011-2013), who had to work through the Salala debacle. She continued to keep the bilateral relationship afloat until she left the post, but both the OBL and Salala incidents had left a deep mark and the Pakistan-US relationship sunk to a new low.

Pakistan ambassadors are not just messengers; they leave their own imprints, believes Dr. Marvin Weinbaum, who has been observing the South Asian foreign policy for decades. He says that usually non-career diplomats bring their charm, style and political leaning that helps frame the message better or sometimes just under-cut it.

While Dr Weinbaum thinks "personalities can colour the message and carry it effectively", he also says that at this sensitive time, the country needs someone very skilled, someone who understands the long history of the relationship yet keeps up a strategy that aligns with the changing dynamics of international diplomacy. The traditional ways of diplomacy are increasingly becoming obsolete, especially when the Trump administration, granted all its naivity, relies heavily on social media and new technology.

The front wall of the main corridor at the Pakistani embassy entrance in Washington shows off decorated frames bearing photographs of all ambassadors who have served there. Six of them were career diplomats, most were political appointees, a few controversial, but each of them has a story of their own.

The very first Pakistani ambassador to the United States, Mirza Abul Hasan Isfahani (1948-1952) toured America as a personal representative of the Quaid, and as the family claims, gave his personal property in the US to the state of Pakistan. His challenges then, in comparison, were hardly as monumental as they are now.

It’s noticeable that the second ambassador, Muhammad Ali Bogra (1952-1953 and then from 1955-1959), steered the terms of the young country’s relationship with the United States that were not discarded by others who served after him. He signed various treaties with the US and secured economic and military aid; making the country extremely dependent, in exchange of offering itself as a front-line state against communism. After a short failed stint as prime minister, Bogra was sent back to Washington to pursue his country’s interests.

Syed Amjad Ali, scion of a Lahore business family, was sent to Washington because of his personal connection and influence. Aziz Ahmad was probably the first career diplomat, before Agha Hilaly (1966-1971), who represented Pakistan. Maj Gen (R) N.A.M Raza (1971-1972) was the first retired army general who was appointed as ambassador.

Considering that the American media and general public do not see military men on diplomatic posts favourably, his military title was dropped in the letter of credence, which described him only as Nawabzada A.M. Raza.

"While East Pakistan was all bloodied [in 1971], the newly appointed ambassador’s top priority was ordering new crockery, and replacing old furniture and a car with new ones," says journalist Akmal Aleemi in his book Nai Dunya ka Musafir. He writes that the day East Pakistan was attacked, Indian embassy in Washington organised a press conference to express their point of view, whereas Pakistani embassy first refused and then reluctantly agreed to engage the press.

"The night Dhaka fell, ambassador Raza was hosting a grand party to celebrate his daughter’s birthday," Aleemi writes.

But another general was sent as ambassador soon after; though this one, Sahibzada Yaqoob Khan (1973-1979), earned a reputation of effectiveness both in America and in Pakistan. He went on to become General Zia ul Haq’s long-serving foreign minister.

Syeda Abida Hussain (1991-1993) became the first female Pakistani ambassador to the United States, representing a civilian government in 1991. By then, the relationship that Bogra had envisioned and forged had passed its peak. Americans were pushing Pakistan to roll back its nuclear ambitions, and the new ambassador was trying to fend off the Pressler Amendment.

In her memoir, Power Failure, Abida Hussain explains that her meetings with US functionaries were rough and often unfriendly.

Pakistan was left in the hanging akin to the situation it is heading towards currently. Every ambassador before and after Abida Hussain was appointed on the sole discretion of the head of the government.

President General Ziaul Haq sent Multan Corps Commander Lt. Gen. Ejaz Azim (1981-1986) and President General Musharraf sent Maliha Lodhi (Dec 1999-Aug 2002). Prime Minister Gillani appointed Husain Haqqani and Sherry Rehman, who had direct access to the top political leadership in Pakistan and were able to use unconventional means to respond to the changing bilateral relationship.

After them, Pakistan has opted to assign only the retiring career diplomats to the ambassadorial position. Since then, the country has also been in a defensive mode, and the relationship has gone from an open and fast pace to a measured and largely clandestine responses.

Career diplomats are not confident in facing the media like political ambassadors and are often seen in Washington as bureaucrats who only follow instructions and that too without enthusiasm.

The so-called uniformity maintained in Pakistan’s policy towards the US has led the country towards diplomatic isolation. "The FATF embarrassment, utterly isolating and shameful as it is, has become the norm for Pakistan. Along with so much else that has isolated and humiliated us this too was stupidly and irresponsibly ignored. The debt riddled ‘development’ taking place in Pakistan has become even more fragile," wrote former Pakistan ambassador to the US, Ashraf Javed Qazi, in his opinion piece last month.

Read also: Diplomatic quagmire

Pakistan, in the last few years, has lost multi-tiered bilateral cooperation, financial and military assistance and much more. It now faces a grave threat of various kinds of American sanctions.

Just like during Abida Hussain’s tenure, the US functionaries are in one voice demanding elimination of militant sanctuaries from Pakistan’s territory. The bilateral relationship desperately lacks common ground and has dropped to the level where it’s only dependent on external events. These relations revolve around nuclear capabilities, Afghan war and global terrorism.

"We can only hope that American and Pakistani negotiators get past the old, stale claims and accusations and try instead to work on concrete measures that demonstrate good faith and common purpose," said Cameron Munter, former US ambassador to Pakistan.

It has been argued that Pakistan’s diplomatic representation is neither politically savvy nor robust. Many US policy analysts firmly believe that Pakistan’s civil and military relations play a major role in shaping its policy and deciding who executes it in Washington.

Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi has named Ali Jehangir Siddiqui as the new ambassador to the US. The government has also asked Pakistan’s current ambassador to the US, Aizaz Ahmad Chaudhry, to continue till Islamabad receives the agreement for its designated man. Siddiqui, however, is facing stiff resistance. Even if the appointment is confirmed, experts say the relationship between the two countries might not see any upward curve because "it’s less about personalities, and more about policies at home."

Personalities are effective only when they have strong backing from Islamabad and are able to colour the message, what Americans believe to be the wishes of Pakistan’s real policy-makers.