Spring in Punjab is greeted by Basant -- the kite-flying festival that started some centuries ago and also became synonymous with Lahore.

Everything about it was positive -- the music, the food, the pretty girls, the night lights of inner city where even the foreign tourists would come to enjoy the sport and partake in the ecstasy of a kite-flying competition which would be lame and extremely serious at the same time.

In those days, people used to fly kites on Sundays and even on workdays. One could see children chase a kite in the afternoons. The kites were large, small, and sometimes so small that one would wonder if they could fly. But they could. Unless a kite had too many holes in it or was broken from every side.

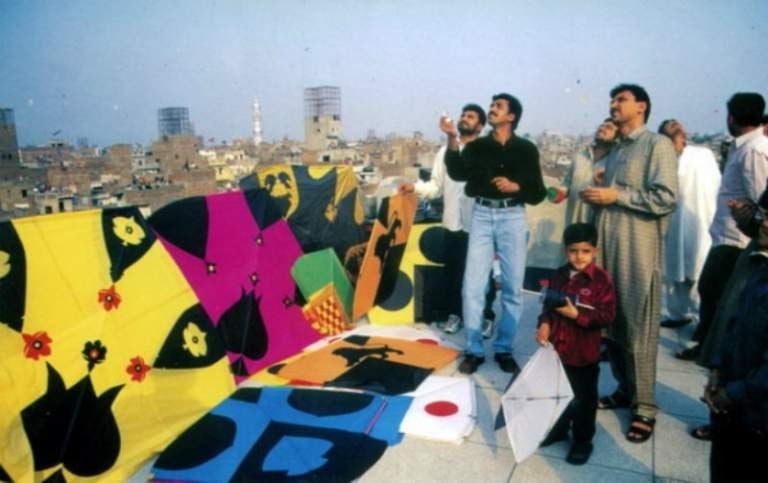

Stacks of neatly organised kites would come by. They were always colour-cordinated -- yellow with green or red, orange with black or blue, and many shades of pink or light blue that could escort any other shade.

Kites of otherwise ‘effeminate’ colours were at par with the more ‘masculine’ shades. And the shapes -- the bat-like triangle that’s small and called ‘gudda.’ And then there was the large, more elaborately designed ‘guddi.’ There is also ‘machar’ and ‘pari’ I personally know nothing about.

The spool also came in different colours but the smartest flyers picked up the lighter shades so as not to be too visible to fellow attackers.

In Lahore, kites worth a fortune were flown in those days, and some fancy flyers from inner city would invest in a glorious kite that would cost a bomb and make it to the newspapers’ front pages. One such kite was flown when I visited my uncle near Mayo Hospital. The kite was red, and seemed to be having frills around it. It didn’t last long and was cut off soon after its flight.

The next day there was news of accidents. People had fallen from their balconies or roofs while chasing kites. Stray bullets also injured people. And then the spool with chemicals was discovered. There was no limit to the damage now -- people would die, have limbs amputated, or barely survive the gore.

I once met a girl in Gujranwala, 10 or 11 years of age, who had been shot during Basant. She was young, thin, fair and, to my little mind, in no way deserving of a bullet which should be the fate of some of the villainous characters on screen.

The last Basant I remember celebrating was near the famed Paan Gali behind Mayo. That was the house of my father’s friend and consisted of tiny rooms stacked on top of each other, and a spiral staircase that connected them. The staircase seemed endless. That evening we had people from the same family on many roofs competing for kites. I still remember borrowing the kite of my uncle’s youngest son and returning it after feeling the pressure on my fingers. The line is always rough on the hands.

The best Basant I ever celebrated was in my own home, some 20 years ago, when a younger uncle from Gujranwala, then a teenager, arrived before it was time for the festival. It was an eventful afternoon when we went on our rooftop, while the sun was shining and some people around us had kites. We didn’t have kites and the only hope was stealing. Soon a stray kite that was pink and black, very new, and large, arrived and my uncle ran after it. He caught it just before the edge.

Our rooftop has high sidewalls so no one could trip over. My uncle stole that kite and many more after that. He competed with a pair of boys on the next roof. I considered those boys to be the nastiest people on earth; though, now I understand they were just having fun. But there was tough competition that day and chants of "Bo kata" filled the air often. That time is gone. Our childhood is gone. And so is Basant.