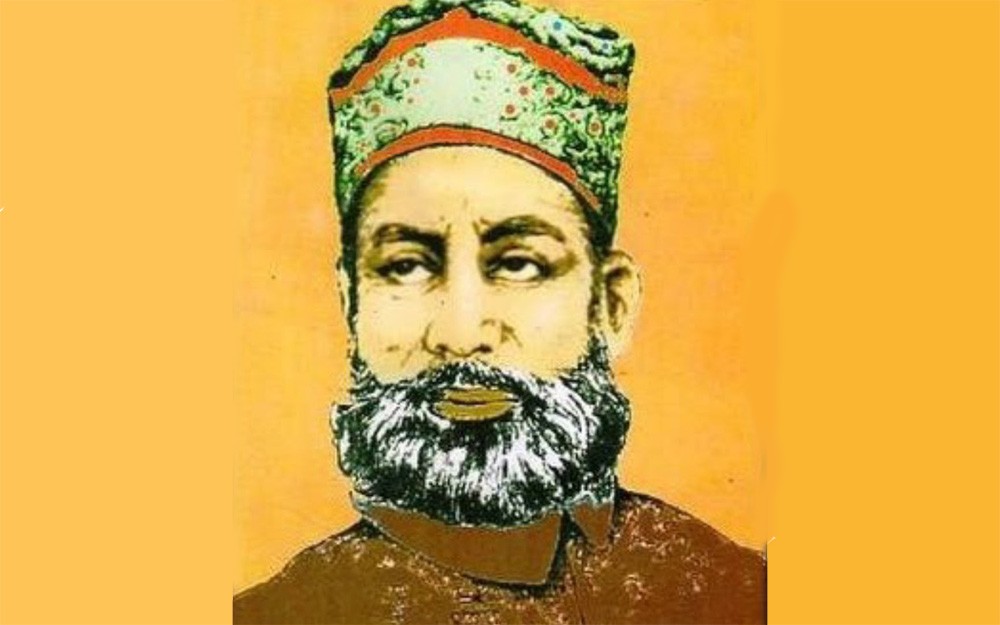

Daagh’s highly stylised and traditional mode of ghazal may have attracted composers and vocalists alike

Daagh Dehlvi is one of the most sung poets. His ghazals sung by leading vocalists have turned into popular numbers. The reason for composers and vocalists’ infatuation with Daagh may be difficult to find out. One reason could be that his ghazals were sensuous and woven with great finery of eroticism.

Daagh was an extremely popular poet in his lifetime. Gradually, his fame and stature waned. It was during the course of the twentieth century that other poets with themes of national and political awakening took precedence over him, not in terms of popularity but in terms of prestige. Perhaps, during the colonial times, it became more valued to be focusing on freedom than to be wallowing in the multilayered and highly nuanced polemics of love.

His major contemporaries were Altaf Hussain Hali and Akbar Allahabadi. While Hali totally switched from the maze of traditional ghazals to first writing about the objective reality in terms of Nature and then to address the need for whipping up the Muslim sentiment in challenging colonisation, Akbar unlike Hali started to pick holes in the "new" in comparison to the certainties of the past value structure. He lampooned the new and glorified the past -- much satisfying those blaming everything on the new and the modern. So satire it was and satire it remained and satire it stayed.

The culture of music, too, was undergoing a change and the salons were becoming a new centre of popular culture tending to replace high culture. Rather than the central court which was unravelling and fritting away, correspondingly the raging provincial princely courts supported the kheyal. Subsequently, the thumri reigned, and in the salons Persian and then Urdu ghazal were gaining currency and raising the level of the vocalists and the genre itself.

Perhaps the admittance to the salons was more democratic, with hereditary and social labels not an essential requirement to be a participant. It is not very clear or documented what was the lyrical content of the ghazals that were sung in the salons. Probably, the poetry was not of great quality and seemed to be more popular in character, meant to meet with the aesthetic demands of a class that may not have been the cultural elite of the times.

During the course of the nineteenth century, theatre also had become very popular and a whole lot of forms were merging there to appeal to an audience that purchased a ticket. A new kind of ghazal and its singing was evolving there as well.

Daagh happened to be satisfying both and addressed either end of the spectrum. He belonged to the classical tradition of high poetry and, by writing in the same idiom, he broached new ground. He was finding solutions within tradition rather than rebelling against it as Hali had done. At the same time, he was extremely sensuous, elaborating on the erotic to create an impression that he fitted into the culture of the salon with his poetry laden with coquetry, amorous asides and extreme sensuality.

The diction of Daagh is such that it is very close to the spoken idiom. Urdu had reached in him a maturity, shedding its Persian skin. It was effortless and easily understood, not laden with heavy complicated imagery. It could move easily at many levels, the most being that it exuded what in local parlance is called "maamlabandi". The connection with high tradition and its transition without becoming totally base and maintaining a balance worked in favour of Daagh as a poet and for the vocalists as performers.

Ghazal must have been sung in the subcontinent for centuries but, since it was considered a low art, no documentation or record is available as may be of dhrupad and kheyal. But, by the end of the nineteenth century, there is greater evidence of the ghazal being sung with seriousness. Ghazal was given a boost by the recording of sound and the cutting of the seven eight rpm discs which were limited to three to four minute duration. This shorter stint suited forms like the emerging film songs and ghazal.

Mukhtar Begum, the leading vocalists of the thumri and ghazal in the first half of the twentieth century, set ablaze the popular music horizon with her rendition of a Daagh’s ghazal "merey qaabo main na pehroan dil e nashad aaya, wo mera bhoolne wala jo mujhe yaad aaya". Inayat Bai Dherowali sang "saaz ye keena saaz kiya jane, naaz wale niyaz kiy jane" while Talat Mehmood sang "dil hee to hai na aaye qiyoo dum hee to hai na jaye qiyoo, hum ko khuda jo sabar dey tujh sa haseen banae qiyoo". Another very popular ghazal "ghazab kiya terey wade pay atebaar kiya, tamaam raat qiyamat ka intezaar kiya" was sung by Muhammed Rafi and later by Mehdi Hasan.

Akhtari Bai Faizabadi set another trend by her rendition of "uzar aane main bhi hai aur bulate bhe nabi-baaise tarke mulaqaat batate bhi nahi’’. This was also rendered by Mehdi Hasan much later. Mehdi Hasan’s "achhi soorat pay ghazab toot key aana dil ka" and Malika Pukhraj’s "zahid na keh buri keh yeh mastaaine aadmi hai" was followed by Mehdi Hasan "ley chala ruth key jana tera" . Later Ghulam Ali sang "tumhare khat main ik neya salam kis ka tha, na tha raqeeb to aakhir wo nam kis ka tha" while Noor Jehan also sang "jaanewali cheez ka gham kiya karen, dil giya tum ne liya hum kiya karen’’.

Daagh’s highly stylised and traditional mode of ghazal is not uni-dimensional, and many meanings and layers can be drawn from it. Attempts have been made to see him and understand him differently from someone given to luxurious amorousness. Initially critics like Khawaja Manzoor Hussain wanted to set the direction right and then Shamsur Rahman Farooqi wrote in great detail about the life, time and circumstances of Daagh’s life and it all emerged in a much more rounded understanding of the man and his poetry.

Daagh Dehlvi’s death anniversary is on March 17. He died in 1905.