Projecting the Pakistani voice in the global arena is essential

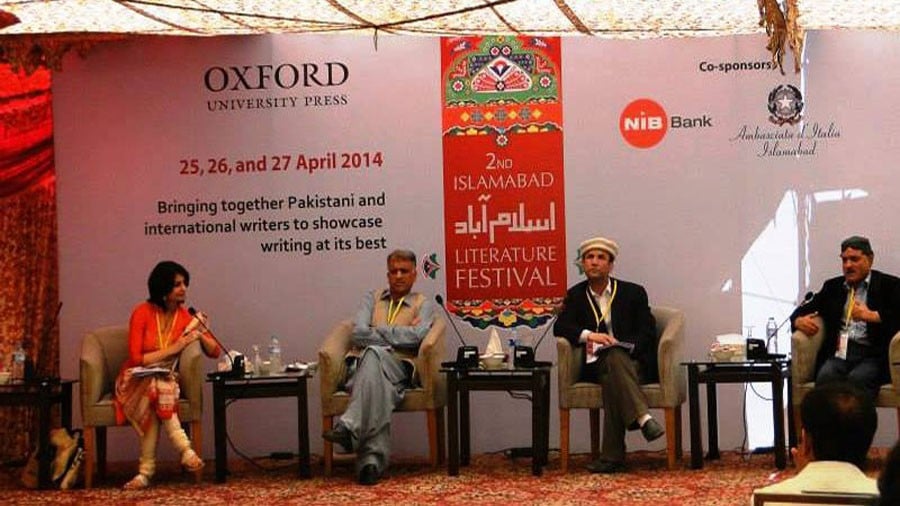

Over the last decade, Pakistani society has made a conscious, if demographically isolated, investment in the propagation of one of its most valuable and vulnerable resources -- its cultural heritage. This drive to continually recognise and celebrate its art and artists has manifested itself largely in urban centres like Lahore and Karachi and in myriad ways -- through art galleries, theatrical productions, and perhaps most prominently, the literary festival.

The Lahore Literary Festival is perhaps the most prominent festival of its kind in Pakistan, not just because of the scope of its programming and the roster of panellists it attracts at home. Since 2016, the festival has travelled beyond Pakistan’s borders, staging two editions each in New York and London, with the aim of translating and magnifying the city’s cultural imprint on a global scale.

Having attended both editions held at the Asia Society in New York, I can attest to the immense interest generated by the event within the greater Pakistani diaspora as well as the more reticent Western audience. To be sure, the goras in attendance were (probably) not of the Fox News-watching variety, but that is an extreme set -- Pakistan’s image as portrayed in liberal publications and outlets, such as The New York Times and The Washington Post or CNN, is hardly more complimentary.

But what does a literary festival accomplish in a country where around half the populace is illiterate, other than indulging a niche, limited image of culture that a privileged elite might like to cultivate? And how does the export of this kind of exclusive cultural event to foreign audiences help the average Pakistani, in any way?

These are questions that have plagued the Lahore Literary Festival since its inception. The logic behind the questions is understandable -- if much of the country’s population is unable or unwilling to participate in this kind of exercise, can it really be said to represent Pakistan, or even Lahore?

It is useful and necessary on one level, because our authors, visual artists, poets and public intellectuals -- the Nadeem Aslams, Shahzia Sikanders, Zehra Nigahs, and Rafia Zakarias, among others -- deserve a stage where they are celebrated, that they can call their own and that they can use to inspire future generations. Still, greater efforts at inclusivity must be made, in terms of the panellists invited, the topics under discussion as well as the audience being catered to.

Another, more urgent function of the LLF is its normalisation of private citizens’ engagement with public spaces -- something that is taken for granted in the West, but is a precious and fleeting enjoyment in Pakistan. This doesn’t mean that LLF has or will single-handedly take(n) back the streets for Lahoris, but it cannot be denied that it has been one of the few cultural events that have attracted interest on both sides of the English-Urdu divide, and that have managed to boost the popularity of public cultural programming among Lahoris.

This is arguably one of the most urgent and well-taken goals of LLF’s foreign excursions. The narrative that paints Pakistan as a nation of, at best, faintly malodorous peasants, and at worst, untrustworthy and treacherous religious fanatics, is too broad and too effective for us to continue to tolerate. Whether this narrative contains elements of the truth is beside the point -- a venture like LLF does not look to deny that those elements exist, but to emphasise that there are Pakistani voices in the world that matter, that these voices will continue to be shaped by the cultural, social and historical context from which they emerge, and in turn, participate in shaping global and local discourses for years to come.

Read also: Editorial

This commitment to subverting prevailing narratives of Pakistan is what makes initiatives like LLF so essential to the reconstruction or excavation of a distinct Pakistani identity -- one that is independent of religion, political affiliation, or class status, and celebratory of diversity of culture, language and thought.

LLF is by no means a perfect institution, but it is an exercise of a Pakistani voice that had for so long been muted out of shame, guilt, fear or complacency -- and that is something to be valued. The projection of this voice onto a global arena is an essential means by which we can control the depiction of our culture, identity and history in the turbulent years ahead.