There are sharp divisions in the country’s literature on linguistic and class lines, and those with money and influence get the lion’s share of media coverage and hype

Posh accents, fashionable attire, celebrity writers that are whisked off as soon as they are done speaking -- the literary festival thrives off an air of cool impenetrability. The bigger the festival the more security and detachment it necessitates, feeding off its own carefully cultivated mystique of inapproachability.

Literary festivals in Pakistan -- particularly their pioneering and most enduring iterations, the KLF and the LLF -- have been criticised for their elitist foundations since the time of their inception. As a response to this criticism a couple of sessions in local languages have been added in recent years.

Even then it’s hard to escape the feeling that non English-speaking panels are a token addition and that the literary festival is really the property of a business-savvy, well-connected crowd that knows how to package literature for a well-to-do audience. Its aim is not an engagement with local audiences, but to be the arbiter of taste for the select few.

A look at this year’s Lahore Literary Festival highlights this point well. Big, brand-name writers like Reza Aslan and Ben Okri are panelists at the event, garnering genuine excitement, but rendering local artists marginal. Perhaps this is what explains the notable absence of major Pakistani writers in English like Mohammed Hanif, Bilal Tanweer and Musharraf Ali Farooqi (the latter two also residents of the city where the festival is being held).

Read also: The roving festivals

In doing so, the LLF has gone beyond the earlier debate of class divides between the English-speaking elite of the country and the ‘commoners’ who speak local languages, going on instead to create a supra-divide between the elites themselves by bringing together a class of international writers and ‘friendly’ notables, while omitting those out of favour.

Interestingly, the biggest draw of the LLF this year is the international movie star and rapper, Riz Ahmed, who played the protagonist in the movie version of Mohsin Hamid’s novel, The Reluctant Fundamentalist. He has also written a moving long-form piece about his experience as a brown actor in Hollywood. His literary credentials beyond that are unconfirmed but bringing one of Time magazine’s most influential people of 2017 to Lahore is a marketing coup for the LLF, a piece of marketing genius it is consistently adept at pulling.

This focus on catering to a certain segment of society places LLF firmly outside of the bracket of Lahore’s masses though, even those interested in literary activities, something I confirmed through a quick survey of Punjab University’s students and teachers of MA Urdu, none of whom had any clue about the festival’s existence.

But there is literary life beyond the big-name festivals, though it may not be quite as consistent or grand in scale. Scholars and academics interested in local languages prefer the epithet ‘conference,’ whose format is more speech than talk-oriented but often serves a similar purpose of promoting literature among a receptive audience.

The 10th edition of the International Urdu Conference took place on Dec 10, 2017 at the Arts Council of Pakistan in Karachi, a big event that has made a regular place in Karachi’s annual calendar, and is very close to the hearts of its large Urdu-speaking and appreciating population. Punjabi conferences in Lahore generally tend to be arranged by educational institutions which limits their audience.

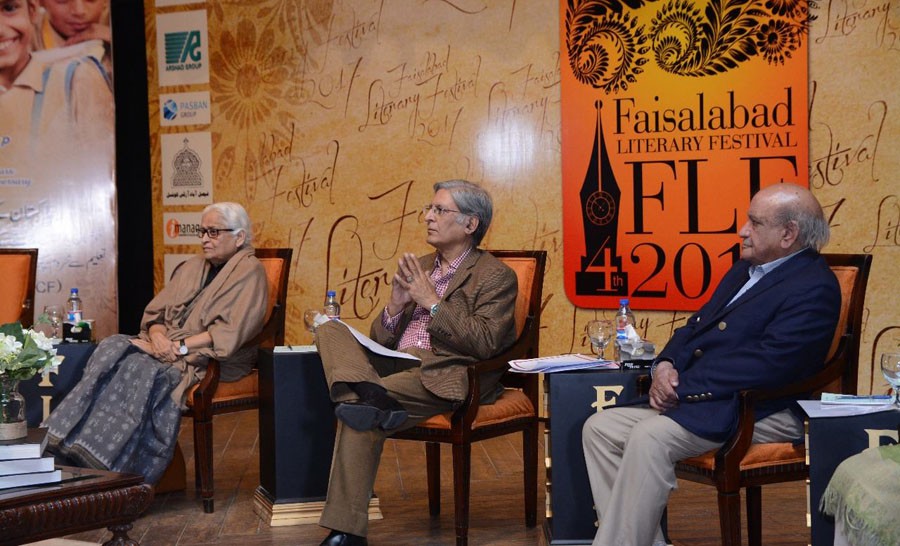

An international Punjabi conference was held at Lahore College for Women University at the beginning of this year, bringing together Punjabi academics from both sides of the Punjab. On February 16 and 17, Lahore University of Management Sciences also arranged an International Punjabi Conference. It is also notable that events in the style of literary festivals have also made their way to Faisalabad, Khairpur and Gujranwala.

But the fact still remains that there are sharp divisions in the country’s literature on linguistic and class lines, and those with money and influence get the lion’s share of media coverage and hype.