Literary festivals can be lauded for initiating a literary movement across the country, which suggests that the less economically privileged towns might have their own small-scale literary events in future

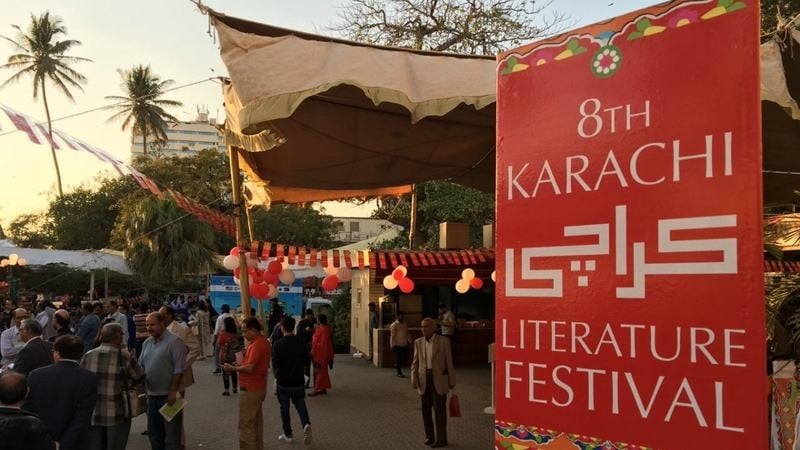

Brightly decorated pavements, roofs adorned with coloured streamers, traditionally painted art walls, small audiences settled in settees arranged in the grassy lawns, swarms of people queued outside fancy halls and marquees, the seflie madness, endless eating opportunities and bookstalls featuring signed copies from authors are some of the common sights at literature festivals across the country.

The literature festivals are not solely about literature anymore, though they include a sublime blend of music, theatre, political activism and engaging discussions.

Though the festivals are seen as a manifestation of revival of cultural in the country and provide an eclectic space to some of the finest authors, thinkers, artists, journalists and celebrities from around the world, the tremendous growth of festivals in the recent past is astonishing considering the challenges that traditional book publishing is facing in the current digital era.

The decline of bookstores and libraries, the commercial dominance of the giant e-corporations, e.g., Amazon, the tilt towards self-publishing among young writers and the changes in the book-reading habits following the popularity of e-books are all raising alarming questions regarding the future of the book business as the primary medium of literature.

Gulzar in one of his poems has expressed the sad affair:

Kitaabain jhankti hain

band almari k sheeshoon se

bhari hasrat se takti hain

maheenon ab mulaqaatain nahi hoti

jo shamaain un ki suhbat main katta karti thein

ab aksar guzar jati hain

computer k pardoon par

Read also: Sold on the idea

According to the co-founder of Karachi Literature Festival (KLF), Dr Asif Farrukhi, "The purpose of introducing KLF was to revive an interest in book-reading culture which has been diminishing over the years. The discussion had started much before among our circle of friends. However, the actual initiative was taken after Ameena Saiyid experienced the Jaipur Literature Festival in India, nine years ago."

The trend of literature festivals in South Asia began with the launch of Jaipur Literature Festival in the pink city of India in the year 2006. KLF was first inaugurated in Karachi in 2010. It is one of the world’s youngest and fastest-growing literary festivals and till date, nine editions of the festival have been held.

From Karachi, the trend moved to Lahore in the year 2013 when Razi Ahmed first established the Lahore Literary Festival. "He was a young twenty-seven year old lad when he gifted Lahore its first literary festival," says Nusrat Jamil, LLF team member.

"In the modern era when there are no platforms for intellectual discussions or sharing of ideas, the LLF is a fantastic development. It’s a not-for-profit initiative and hence, a true labour of love. We have an energetic volunteer base of young people who put in all their efforts on the two days of the festival," says Jamil. "Currently, LLF is the biggest literary show happening in the country and we are proud that we have been one of pioneers in introducing the idea which is now spreading to smaller cities," she says.

The literature festivals have now moved to smaller cities, such as Faisalabad, Hyderabad, Gujrat and Gwadar -- to an extent, challenge the emerging narrative regarding the declining interest in literature and changing reading habits.

However, the literary festivals have been previously criticised for drawing a more general audience than literature enthusiasts. Also, the festivals have been rebuked for their reverence to intellectual elite and for little to no contribution in promoting the works of indigenous writers and poets.

"It’s only a small group of people who has the power over the literature festivals. They have mostly neglected authors and poets that don’t belong to a certain powerful literary circle. Also, they give more importance to authors from abroad than the Pakistani writers and poets which c diverts the public attention from local literature," says Ashfaq Saleem Mirza, the veteran author and philosopher. "Moreover, now that the festivals have introduced music and dance, they are no more literary but have become art festivals."

During the sixth edition of LLF, Abdullah Hussein, one of the greatest authors of the subcontinent, was provided a stage in Adabi Baithak which hardly has a capacity for 150 people. On the other hand, foreign authors were given a space in Hall One. A huge crowd had queued up outside the hall eager to listen to him. A few people from the audience protested saying that this is not a suitable hall for Abdullah Hussein. They condemned this discrimination against local authors.

Responding to the general criticism, Farrukhi explains, "We have whole-heartedly welcomed Urdu and indigenous writers, such as Kishwar Naheed, Intizar Hussain and Amar Jalil to name a few.

"The selection for sessions and writers at the KLF depends on topicality. How wrong would it be if people label us for not considering Mir Taqi Mir a great poet just because we have not had a session on him, so far? People have attached their high hopes with us and unfortunately, we can’t fulfil them all."

Regarding the session design and planning, Farrukhi says, it’s done by a small team, "Like I came up with a session named Hijrat, Yaadein aur Khwab. So, I conceptualised it and wrote a short description explaining it. Similarly, other team members come up with their ideas for sessions. We also seek suggestions from our friends while planning."

While the KLF introduced the idea of literary festivals to Pakistan, Farrukhi mentions that they don’t own any copyrights for that and he is happy that smaller events are now being held in different parts of the country. The festival has also been held in London and New York. "The response has been amazing. The main purpose is to build a progressive image of the country that is only known for terrorism in the West. People in London were really surprised by the Peshawar-based band called khumariyan at the LLF," he says.

Despite all criticism, festivals can be lauded for initiating a literary movement across the country, which suggests that the less economically privileged towns might have their own small-scale literary events in future.

As for authors, a good festival experience surely depends on the success of their own session. By providing a stage to authors, the literary festivals have raised them to the status of celebrities, a privilege that has previously mostly been held by film actors or musicians. However, most of these festivals are free and open to public.

Being commercially sponsored events, the festivals pay people who supply services, such as marquees, chairs, brochures and banners for publicity, the rent for the venue and administrative costs. The performing artists are paid in millions while no fee is offered to authors and poets. Perhaps it’s about time to begin a discussion about why the writers are insufficiently rewarded or expected to appear for nothing much in return.