Our disengagement with history has caused exclusionary nationalists narratives to take hold in the popular imagination in both India and Pakistan. Hence, everyone is either a Hindu or a Muslim and there is no other identity beyond this singular dimension

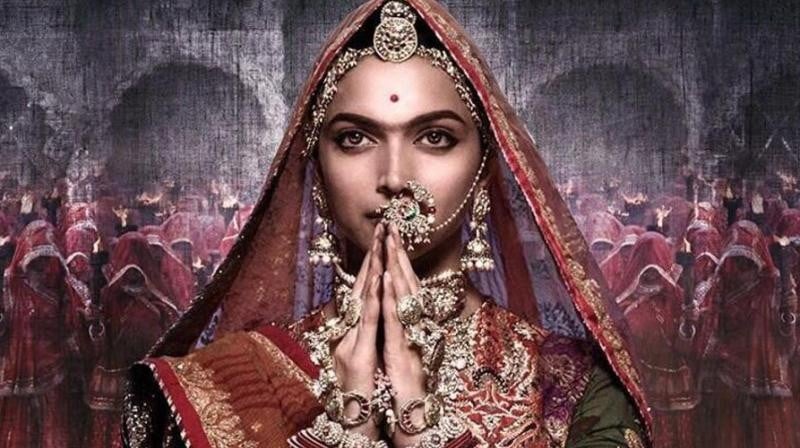

Lately the film Padmaavat by the acclaimed Sanjay Leela Bhansali has elicited a lot of charged comment. Set in 1303 AD, this film -- before its release -- enraged right wing Hindu and Rajput groups in India because it was thought that it showed Padmaavati, the Rani of Mewar, in a negative light in comparison to Allauddin Khilji, the Sultan of Delhi. However, after its release the tide is flowing the other way, with Rajput and Hindu groups largely happy with the film since it shows Padmaavati as the epitome of honour and valour, but now Muslim groups are bewailing the negative portrayal of Khilji. Either way, it is interesting that for a film so many emotions were enraged, protests held, and even the lives of people threatened. So what is the issue here?

First, we must stop expecting films to depict reality or follow historical facts. Films should be treated as, well, films, and not a history lesson. Films are meant to be fictional depictions, and hence there is a disclaimer before almost all films. Films might be inspired by real life events -- and some really good ones are, but expecting them to stay true to the historical narrative is wanting something which this genre never set out to follow. Put succulently, a film, which is faithful to its historical reality, is actually called a documentary.

In the specific case of Padmaavat, the long disclaimer before its start clearly showed that it was a work of fiction and that expecting it to be an exact depiction of reality was flawed to begin with. Rather than any historical account, the film is loosely based on the epic poem with the same name written in 1540 by Malik Muhammad Jayasi in Awadhi. Hence, it is an adaptation of an already fictionalised account, unless of course one thinks that the talking parrot in Jayasi’s poem, for example, was real, or that the Ocean speaks to Ratan Sen, the ruler of Mewar.

The epic poem was surely inspired by the reality of the Khilji attack on Chittor in 1303, and the historically recorded Jauhar (self-immolation) of the women there, but beyond that it was mere fiction about the Rani, her unmatched beauty, and Khilji’s lust for her. Therefore, taking the film or the poem which inspired it, as historical reality is simply wrong.

Secondly, we must stop seeing South Asian history through the binary of Hindu vs Muslim. It is true that John Stuart Mill divided up Indian history according to the religion of the rulers, but over a hundred and fifty years later, we do not have to follow the same distinction. In the film, for example, Khilji never uses the word ‘Islam’ or ‘jihad’ and there are only a couple of fleeting references of his religion. The fact that people are viewing Khilji only through the prism of him being a Muslim (and that too nominally, according to most historical accounts), shows how we continue to read our mono-dimensional religious identities into the past. The same is true in the case of the Rani, where everything she does is understood as emanating from Padmaavati following her religion.

Thirdly, while some historians, on both sides of the Radcliffe Line, have blasted the historical inaccuracies of the film (after all, bridal India is only a recent phenomenon), the real problem is the lack of any public resources for the teaching of history. There is no channel in South Asia comparable to the History Channel, which shows documentaries and shows relating to our history, for example. There are also no programmes dedicated to the study and investigation of history in state televisions or other channels in South Asian countries. In fact, there is no public engagement with history at all in our region.

The real problem, therefore, is not with films that fictionalise historical accounts, but with the lack of engagement by historians and public scholars with visual mediums. This disengagement only leaves the fictionalised films as sources of history for people, creating bizarre and skewed notions of history in the minds of the people. Therefore, the onus is on scholars and other interested people to create avenues for the dissemination of history through visual mediums so that a critical sense of history is created and that films are left to what people like Bhansali do best -- create good drama.

Finally, it is interesting to note that this is not the first time that the story of the Rani of Mewar has been depicted on screen. In 1963, the distinguished actress Vyjayanthimala played the Rani in a Tamil release, Chittoor Rani Padmini, while a year later the Hindi version of the story came out under the title, Maharani Padmini. Both these films did not too really well and elicited little comment, let alone protests.

So what is the difference now? The change is that our disengagement with history has caused exclusionary nationalists narratives to take hold in the popular imagination in both India and Pakistan. Hence, everyone is either a Hindu or a Muslim and there is no other identity beyond this singular dimension. Films are also supposed to depict this and therefore even without any clear reference to Islam or Jihad by Khilji in the Padmaavat movie, all his actions were seen through that prism.

The rising tide of Hindutva in India and Islamic extremism in Pakistan will only solidify these divides and strangle the rich mosaic of history in South Asia. Therefore, unless we act now and start engaging the public with our history, create more visual media materials, and have an open and dispassionate discourse, the politics of exclusion, hate, and discrimination will continue to choke our state and society.