Hidden behind the glamour and glitz of beauty salons are hair-raising tales of exploitation

Salon workers are often touted as examples of young, enterprising, independent women who are financially supporting, or even running their homes. But the grime of the beauty industry is hidden plain sight, like calluses on the feet they scrub.

Sarah has seen the grime up close. She began her career in the beauty industry seven years ago at a mid-range parlour in Gulberg, Lahore. Since then she has worked at high-end parlours on M. M. Alam, for an app-based beauty parlour service, and currently is an independent ‘waxing woman’.

"The whole industry is tough, but some owners and bosses are definitely more exploitative than others," she says. Since beauty parlours in the country are not regulated or registered, working conditions vary from ‘terrible’ to ‘worse’. Salon owners are constantly competing with each other to provide customers with better, cheaper, and more exciting deals, as a result of which they are competing with each other for cheaper workers.

No matter how exploitative their job may be, the women hang on, because the next parlour seems even less green.

Sarah’s first foray in the industry was as a "trainee" and her terms of employment, if it can be called that, were clear: she would work 9 hours a day, 6 days a week for no pay. After three-six months depending on how fast she picked up skills, she would become a salaried employee earning a grand total of Rs3000 a month. Her salary would grow, she was told, but there was no timeframe they could promise her.

Sarah was not upset by these terms. "Yehi rate hai market main untrained girls ka," she says. "You have to work hard and learn many skills before you can be promoted and ask for increments."

Read also: Learning to ‘make-up’ a living

I tell her that the law states that she cannot be paid less than Rs15,000 for a full time job, even if she’s untrained. She’s silent for a moment and then says: "Maybe the owners don’t know the law?"

But interviews with salon owners from Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad reveal that the law is known, but ignored. One salon owner from Islamabad, Zainab, says, "If I start paying every untrained worker Rs15,000, I would go bankrupt". Another, in Lahore, says that "We should be charging these girls for training them, instead we are giving them pocket money for petrol, they should be grateful to learn." Some salons provide workers with ‘pocket money’ or ‘travel costs’ upto Rs3000 during their training.

And the fact is that many young women across the country are in fact grateful. "With no educational diplomas or degrees in hand, the salon is often the only option for us," says Saba, a Karachi-based salon worker who has been in the industry for 4 years.

Women are also grateful for this opportunity because the beauty parlour is one professional environment where they don’t have to interact with many men, and this adds a false layer of security for them and their families. "You can work in a parlour and still maintain your izzat [honour]," says Sarah. "For instance, a parlour girl is considered less izzatdaar than a housewife, but far more izzatdaar than a lady working at a checkout counter at KFC or McDonalds".

Does she think she compromised her izzat for this career? "No, no, that’s just what society thinks. I am putting my son in school with the money I make, what can be more respectful than that?" she says.

***

It cannot be argued that the exponential rise of beauty parlours across the country has put these women on the path of financial independence; but it wouldn’t be cynical to ask where this path ends, and what it’s costing the workers?

For one, their health is often on the line. Beauty parlours in Pakistan have almost no health regulations to protect their workers. A report in The New York Times in 2015 told "stories of illness and tragedy abound at nail salons across the country, of children born slow or "special," of miscarriages and cancers, of coughs that will not go away and painful skin afflictions". It reported that "a number of studies have also found that manicurists, hairdressers and makeup artists have elevated rates of death from Hodgkin’s disease, of low birth-weight babies and of multiple myeloma, a form of cancer".

Needless to say, no research of this kind has been carried out in Pakistan. The women say that they haven’t really heard much about this. "Often someone’s cough will persist longer than it should, and of course infertility and miscarriages are huge issues amongst our age group," says Saba, the salon worker in Nazimabad, Karachi. "But who’s to say those are because of our work at the salon and not just our diet etc?"

There has, of late, been a shoddy governmental movement to teach salon workers about the spread of Hepatitis B and C, HIV, AIDS and Thalassaemia. Note, this is not to improve conditions for the workers, but in fact to protect the customers.

In any case, salon workers interviewed by The News on Sunday from Lahore and Islamabad knew nothing about this move. A few salon owners, however, did. "This is nothing but a ploy by the government to force us to register our salons. They think we will register them in order to get this free training, but I just told my workers myself to be careful not to prick anyone," said Ayesha, a salon owner of a mid-range salon in Lahore.

And while these women may be on the path to the promised land, there is no certainty about where each workers’ path will end.

Early in her career, Sarah learned that most parlours follow a similar organisational structure where workers are pitted against each other so regularly that they have no time to rebel against the owner. The hierarchy within beauty parlours is reminiscent of British-era divide and rule policies: Managers and workers are two different streams, and one can never jump stream. You can flow upward though, patiently. Very patiently.

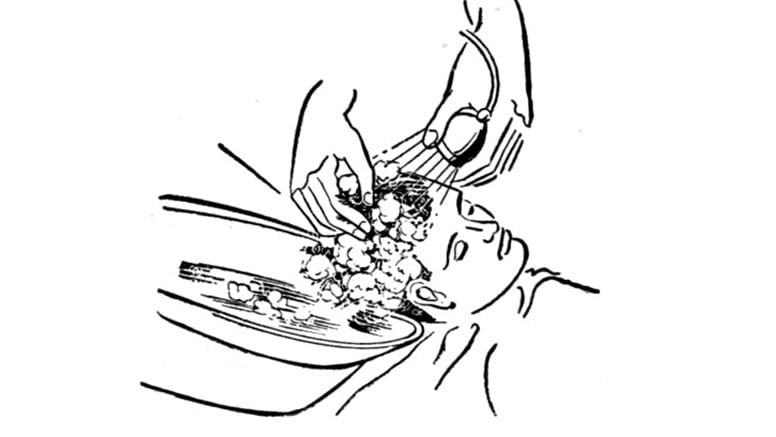

Trainees eventually become juniors, i.e. those who do manicures and pedicures, then as you are taught skin-care, which includes facials and skin polishing, you jump up another pay scale. The highest two rungs are the "seniors" -- women who style hair and do make-up.

It’s straightforward enough, but very few make it all the way. "Seniors and bosses, across the board, never want to teach you hair and make-up," says Umber, who works at a parlour in Icchra, Lahore. "You need many more junior girls than senior girls," says Zainab, the Islamabad-based salon owner. Think about it, you can go in for a manicure four times a month, but you will only get a hair-cut or party make-up done a few times a year.

This means that many women who may be ready to go up the ladder are stuck there for years.

***

Sarah never made it to the top. Her job at the M. M. Alam parlour ended because the salon shut down in mysterious circumstances. "We went to work one Monday and there was no parlour there anymore. The chairs, mirrors, sign were all gone. Ma’am gave all the trainees Rs500 [out of good will] and sent us on our way," she says.

When she got her next job at a parlour in Gulberg, the owner said she has to start from scratch, because she may be "trained" but she wasn’t trained well enough for her parlour. So Sarah cleaned feet for another two years, at the end of which her boss still didn’t allow her to learn hair and make-up. Fed up with the system, she quit.

This begs the question that if Sarah could quit upon realising that she’s being exploited, why can’t others? While bonded labour is conceptually illegal in the country, it nevertheless prevails in parlours (not to mention our homes).

Many parlours across the country only allow a trained girl to quit if she is getting married, or moving cities. After the trainee period, they are asked to sign 3-5 year contracts, and they are told that if the contract is violated and they are found working at another parlour, there will be a court case against them.

Najma, a salon worker in Islamabad who has only recently begun working for Zainab, says that her previous boss was "buhat zaalim"[a tyrant]. She worked there for Rs10,000 a month, including tip, for three years because she feared that the boss will generate a fake F.I.R against her. "She threatened to do that whenever anyone tried to quit," says Najma. Till now, there’s been no case, but Najma is still fearful.

A third empty but common threat salon owners make is that "if you leave, I will call all the other salons and tell them not to hire you". Given the sheer number of parlours in the country, the threat seems impossible to play out, but it affects workers who consider their boss as a benefactor.

Sometimes there is also emotional blackmail. Sarah says before she quit the M. M. Alam parlour, her boss tried to keep her on by saying "I have taught you so much, now you will be namak haram and leave me? You will never be successful like this."

As empty as they are, the emotional blackmail and scare tactics work. They didn’t work on Sarah since she comes from a family of salon workers: her sister, two cousins, an aunt, her mother all work at salons across the city. "But I have seen girls tremble in fear of FIRs and law suits against them," she says. "I’ve never actually seen it play out though, so I am not afraid of these threats."

The salon owners make a case for their defence. "The instant a girl is trained, she leaves you for a better job, and then you start from scratch with another girl. This lack of professionalism is very frustrating" says Zainab, the salon owner from Islamabad. "We have to try and retain them. At the end, those who want to leave, will leave, but we have to at least try to minimise the turnover."

Why not just retain them by increasing their salaries and improving their work conditions, I ask her? "That would upset the whole system that’s already in place," she says.

***

On a slow Tuesday afternoon, a high-end beauty parlour in DHA, Lahore is paid a visit by their cutest customer to date. The girl is not yet five-years-old but is tired enough by life to want a foot massage. Her mother is on another floor of the establishment, getting a facial, and this little one has made her way upstairs, two maids in tow, demanding service.

The workers are not put off by having to serve someone less than half their age. They find her charming and adorable. I ruffle a few feathers by softly asking if they think this is a waste of good money. "Those who have money, spend it. What’s it to us how they spend it? Look at how happy the massage is making her," says Saba, a junior worker at the salon.

Ifrah works 6 days a week, 9 hours a day, doing manicure, after pedicure, after manicure. Then she goes home, hears her husband yell at her for leaving the children with his mother all day, serves everyone food, prepares food for the next day, and sleeps. Each manicure costs Rs1,200. Ifrah says that she does 6-7 manicures in a day, which adds up to 144 in a month. That’s Rs172,800 for the salon. Ifrah is paid Rs8,000 a month, and double that in tips and commissions, leaving her a total of roughly Rs24,000.

To be fair, Ifrah is happy with the amount she makes. She just wishes she didn’t have to work till 8 pm, and that she didn’t have to work when she was sick, and that it wasn’t so physically exhausting, and that the owner screamed a little less, and that she could have some Sundays off. She’s Christian -- as is a large swathe of women working in parlours -- and misses going to weekly Mass. But other than all this, she’s happy, she says.

She also wishes customers were nicer and didn’t create a scene every time the workers made a tiny mistake. As she’s whispering this to me, another manicurist plucks too much cuticle off a customer’s hand. Shouting ensues and many workers rush to placate the customer. I am told this is a fairly regular scene.

***

At a less high-fi parlour near Bedian Road, Lahore, things don’t seem as tense. The owner is rarely around since she runs four businesses: a restaurant, a dye stall, a lace shop and the parlour. The manager and three juniors are squashed together on a pink two-seater couch, watching Cinderella, on a smartphone, dubbed in Urdu. "It’s been a slow day," they tell me.

At the face of it, you’d rather work here than a busy DHA parlour because at least you get some down time. Unfortunately, this is false. The women are paid a measly Rs2000 a month, a contribution towards travel costs. They work purely on commission, they tell me. Meaning that they are paid 5 per cent of every service they perform. If on a certain month, their commission adds up to more than the basic pay, they get only the commission. "Decembers are the busiest and this time I made Rs7000 in commission. I expected to take Rs9000 home but the owner said its one or the other, not both," says Mary, a junior worker at the salon.

Working on commission is too common in the industry. The Islamabad-based salon owner believes that 80 per cent of salons probably employ that method. "It’s smart, right? You don’t spend too much on the workers and you put the onus of convincing clients to avail more service on the workers," she says.

She reminds me of all the times I have walked into a parlour just to get my eyebrows threaded and I have been told that I need a facial and hair oiling most desperately. "All those women don’t really think you need a facial, they just really need that commission."

If salons across the country were regulated and registered, then these women wouldn’t have to cajole customers into facials and the likes, they would have a standardised pay.

Another reason to support the regulation and registration of beauty salons is because the beauty market is suspected to be worth millions, if not billions. Just take Punjab, as an example; currently the Punjab Revenue Authority earns up to Rs8 million from the 287 registered salons across the province. It is estimated that there are at least 2,000 salons in the province, meaning that the FBR is losing out on an annual tax revenue of Rs42 million.

Currently, the data available about the number of parlours and the revenue they generate is limited since many salons are being operated from households, and many parlour owners in commercial areas, do not hang signs outside their establishments in order to avoid paying taxes.

***

After The New York Times story on manicurists’ working conditions in New York City, laws were passed "requiring salons to display a workers’ bill of rights; the state also launched an inspection task force and launched an education campaign to inform workers about labor laws and their legal rights".

This will take years in Pakistan, maybe decades.

But Sarah has a simpler idea to improve working conditions. She asks why customers can’t be just a little more conscious? "Shouldn’t they have a role in all this?" she says. She believes that regular clients should care about the well-being of the workers. After all, a beauty salon is a unique working environment in the sense that it’s not just a relationship between the worker and the owner, but also between the worker and the client. "If you see that your regular girl is sick, ask the management to give her a day off. If you see that she’s been fired, demand to know why. Ask your regular how much she is paid and when she expects a pay raise," says Sarah.

Her point is that they may not give her the day off, and may not hire her back, they may not even give her a pay raise, but if they realise that customers are put off by the bad treatment of workers, they will be far more inclined to improve working conditions.

For now, Sarah has left all bosses behind and is working as ‘waxing wali.’ The clients she has cultivated in the last 7 years call her to their house for parlour services. "This is the first time in my life that I get to keep what I earn. Maybe one day, I’ll go back to a parlour, but only if they hire me as a junior, never as a trainee," she says.

Names of the working girls and owners have been changed upon their request.