Shahid Hameed’s life proves that if one wants to do substantial work, one has to set priorities and preferences

The generation of 1920s and 30s is waning fast. Yet those who left something in writings and recorded memories will be remembered, by admirers and critics alike. These generations not only observed communal harmony but also communal segregation. They lived the narratives of nation-building and then saw these ideas being split across borders. Their anger, anxiety and idiosyncrasies deserve to be digitised because when this generation is no longer present, it is with these records that we will remember them.

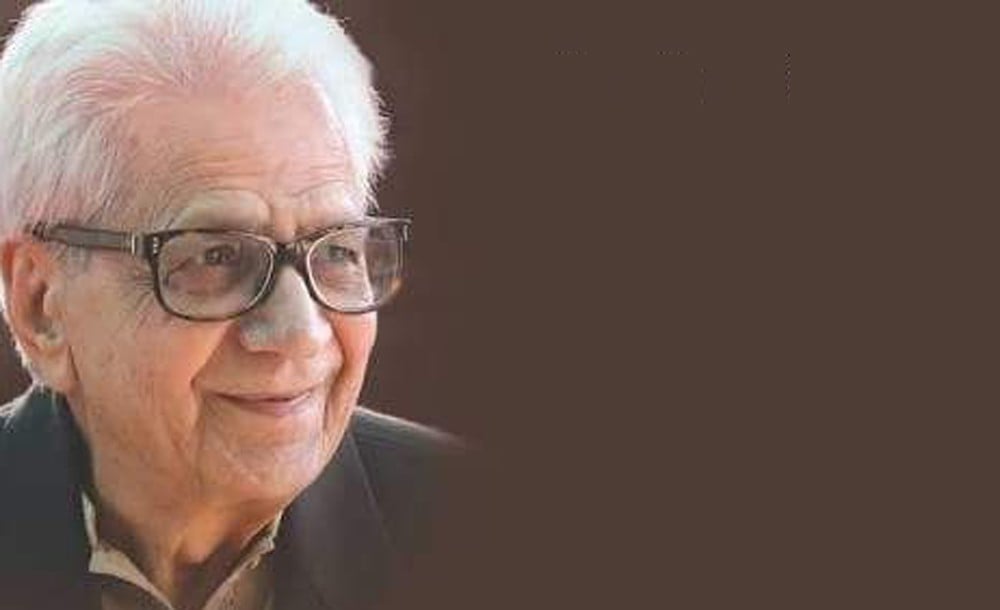

Shahid Hameed is one such individual who not only left a huge body of work but also shared his experiences and memories under the title Gayee Dinon Ki Musafat.

I first read Hameed’s translations of War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov and Sophie’s World. Later when I joined the publishing wing of Readings, a bookshop in Lahore, me and Hameed got to know each other better. I also learnt that he was an acquaintance of my grandfather’s and I took this oppurtunity to interview him.

Hameed was born in the fertile district of Jalandhar, Punjab in 1928 and was very fond of his village, Parjean (Parji is sub cast of Arains), and the area around it called Nakodar.

Till his last days he remained a staunch admirer of Chotu Ram, a Jatt Punjabi visionary who broke the backbone of the All India Congress in the late 1920s and mid-1930s, by passing three unprecedented amendments in the Punjab Land Alienation Act 1900 against moneylenders.

Shahid Hameed was disappointed with those who designed the curriculum of Pakistan for criminally ignoring Chotu Ram’s services. He felt they did this due to his religion and his association with the Unionist Party of the Punjab. Hameed was an admirer of the Pakistan Movement, Allama Iqbal, and Quaid-e-Azam but he did not hate Unionists and Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam, a Muslim party that opposed the idea of Pakistan.

After the annexation of Punjab, in 1865, the colonial masters expelled Persian and imposed Urdu in its place. This policy continued after the creation of Pakistan. Hameed translated many books into Urdu and highlighted several issues related to misleading Urdu dictionaries. However, his partiality to Urdu was not premised on hate for Punjabi. He was deeply aware of pre-colonial Perso-Punjabi traditions and wrote: "I am proud of my Punjabi identity and love of Punjabi language and I know that we had a strong Perso-Punjabi past which was destroyed by the colonial rulers after the annexation of the Punjab…Our teachers were very smart, so they often used Punjabi in classes informally and I recorded many things in my book too. We should introduce Punjabi in schools. There is no alternative to the mother tongue".

Before becoming a teacher, he worked as journalist. He always spoke fondly about his editor, the acclaimed intellectual, Professor Sarwar of Ubaidullah Sindhi fame.

He never joined progressive politics nor found any sympathy for radical Islamists or those who created the ideology of Pakistan. Unlike his friends, he linked the rise of extremism with religion-based anti-communist policies that began after the passing of the Objectives Resolution, in the formative years of Pakistan.

"Intizar Husain was against progressive thoughts while I was more of a moderate" said Hameed. In a recently published autobiographical account titled Surkh Syasat, Abdur Rauf Malik wrote a detailed account against communism and state oppression that started in literature and media first, and was later transmitted into politics.

A moderate by conviction, he felt no hesitation in mentioning this book. According to him, those who promoted religion-based anti-communist campaigns in media, education and literature during the 1950s laid the foundations of extremism in Pakistan. Thanks to US-led Western alliances like SEATO and CENTO, these misleading narratives got umbrella protections. After 9/11 many of them gradually began realising the fatal effects of that narrative; unfortunately however, they are still reluctant to deconstruct it.

As Hameed was a compulsive translator, he extensively employed dictionaries and lughats during his work. Soon he realised the role of Urdu dictionaries in the downfall of Urdu Language.

"I realised that students cannot learn Urdu in the presence of these infected and confusing Urdu dictionaries," he said. The publication of Qaumi Angrezi-Urdu Lughat by Dr Jameel Jalibi proved to be a breaking point for Hameed in 1986.

He wrote a detailed criticism of the dictionary in which he not only pinpointed difficult and more complex word-meanings but also raised questions regarding pronunciation. That exercise encouraged him to finally create an English to Urdu dictionary.

Shahid Hameed hailed from an ordinary, humble background. But he not only managed to carve out a wonderful life for himself, but also for his children. "After partition, we settled in a village that was 16 miles from Cheechawatni. It was a very difficult time and I was married and had many responsibilities. The Vehari Bus Service, owned by a Sikh family, was the only mode of travelling. Our village was three to four miles away from the bus stop and we had to walk to get a bus.

Then I shifted to Lahore in search of job. I started teaching in a school and working for a newspaper. In newspapers, I often did night duties".

In this world of PhDs, awards and conferences, Shahid Hameed remained honest and devoted to his work. He neither ran for lucrative posts in the institutions he worked at nor marketed his personality. He was unusual in many ways, but his life proves that if one wants to do substantial work, one has to have priorities and preferences.

Until his health allowed, in his leisure time, Hameed loved to meet stalwarts like M. Salim Ur Rahman, and youngsters like Mehmood Ul Hasan. The world will continue to remember him for his works and contributions.