Mudassir Bashir’s stories, concerned with human conscience and folly, are recommended for readers of Punjabi fiction

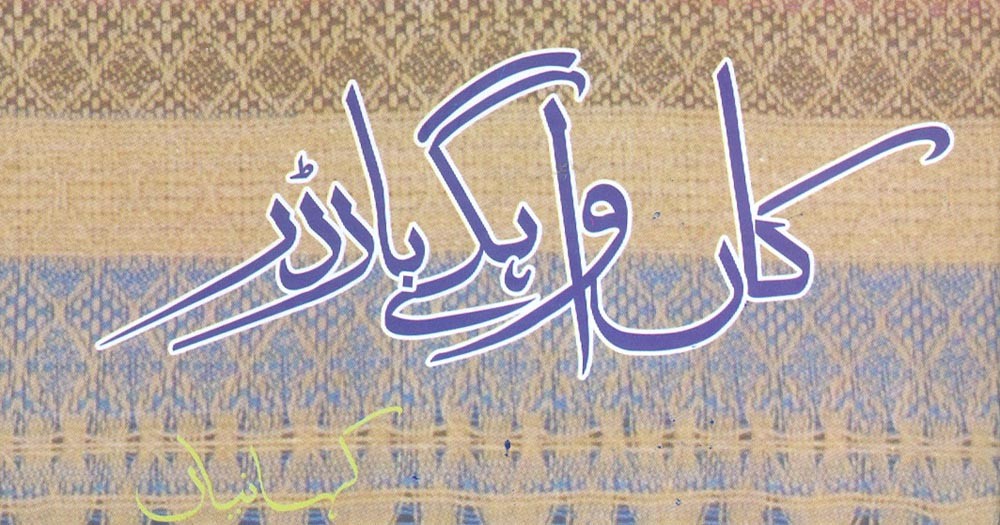

Mudassir Bashir’s latest offering KaaN Wahgay Barder is a delightful little book with 12 stories of varied length and range, both emotional and intellectual. A writer is a mapper of a society’s emotional and political mood, just as he is a measurer of time’s kindness and cruelty towards the most vulnerable. Bashir’s main concerns in the book under review are primarily human conscience and folly. His diction is modern but controlled, which grounds a majority of his subjects and what matters to them. But those who have followed Bashir’s work closely know his passion for history, especially of Lahore and thus by extension Punjab.

Underneath his fiction the reader senses a concern not just for the people but the place they inhabit, which offers its kindness equally to humans and animals. It pains Bashir to note that his fellow Lahoris are not kind to animals. A humanist at heart, he views his characters, weak and fickle, pitted against a system that is stubborn and uncaring.

The endings of several of his stories reveal Bashir’s faith in humanity rising to the occasion, if not to solve the problem, then to console the aching heart, relieving momentarily the fear of loneliness.

This tendency, I feel, sometimes weakens his stories a bit and distracts from the magic he is so good at casting, the believability of the characters, their world, the drama and the tension he creates, be it in the form of a conversation as in the opening story of ‘Dipty Commissioner’ which brings two old acquaintances together after several decades; or be it in the form of a reluctant amorous rendezvous between a well-known singer and an infatuated young woman in the fairly gripping ‘Circuit Shot’. Or even his very endearing ‘Langra Samaj’ and ‘Moonh Parnay’.

‘Dipty Commissioner’, though a little weaker than the others I mentioned above because of its straightforward narrative technique, sucks you in nevertheless as the two men begin talking to each other, dropping their guard, letting the human in each reach the other. And in doing so, the author, without being judgmental towards the Deputy Commissioner for his privileged position, which ironically happened because of the man he is talking to, the owner of a shop that repairs punctured tyres. The twist the reader learns, though verging on cliché, doesn’t make the story limp because of the pace and humour of the narrative as they sit recounting their school days. When the Commissioner departs, his promise to stay in touch, "hun milde ravaan ge", does not ring true and seems forced. But the reader is willing to let it slide because the story does not end on a moralising or judgmental note. Instead, it draws our attention to the Commissioner’s shadow which melts into the shadow of the night.

The other stories, stronger and more complex, end up conflating the author’s desire to leave a moralising note with that of the narrator.

In ‘Circuit Shot’, the amorous rendezvous does not go smoothly and as the story reaches its climax, Bashir shows the constraints modern Pakistani city culture imposes on its young men and women, and when utter panic takes hold of the main character, he and his friend manage to escape, leaving the girl and her mother on their own in the amusement park. His friend is as taken aback as well as the reader, even disappointed perhaps, when the protagonist brings his friend into the mosque to offer prayer. When the friend, baffled, wonders why suddenly the namaz tilt, pat comes the answer: "Be quiet. Move on. If not now, then when else would you pray?" This urge to leave an iron, teasing remark should be resisted. It seems to come not from the character’s mouth.

‘Moonh Parnay’ suffers a similar fate. For the most part it is a refreshing portrait of a rather simple man who enjoys female company and is not too worried about social or religious morality. So far, he’s been able to sleep with all the women his wife employs for household help, except one. He eventually wins because he’s learned that money can soften the pride of the poor. The stronger part of the story is how he’s built the character of that woman, who knows how to negotiate her sexuality, her place on the margins of society and her agency. So he succeeds in bedding her, but is disturbed by the fact that the woman has not kissed him on the mouth. He confronts her and she tells him the money wasn’t for kissing. Sometimes, it is wise to leave certain things unsaid or else you risk destroying a well-crafted, delicate story.

The story where his craft is at its peak is ‘Pichchay Murkay na Vaykheen’. It shows, without a sermon, a struggle between one’s sense of duty to family and work ethic, which is lacking in the main character, a low-level police official. Bored and uninspired by his job, he needs to make some extra cash tonight before he heads home. Not a lot, just a little cash. He’s met with one comic disappointment after another. The story never for a moment allows the reader to feel contempt for the pathetic policeman, as it oscillates between humour and empathy. It conveys the sense that even when people commit misdeeds, there remains in most of them a touch of humanity.

It is this touch of humanity which connects the reader with Bashir’s characters. I also feel that because of his diction and his tremendous love for the world from which his characters come, he doesn’t allow his stories to enter dangerous and dark spaces which might challenge his language and the plotlines a bit more. But you can’t force a writer. He writes about what excites him and we should be happy and content with that.

I highly recommend this book to those who would like to read Punjabi fiction but are either reluctant or ashamed. Bashir’s language is humorous, crisp, modern and it should resonate with those who like a good story.