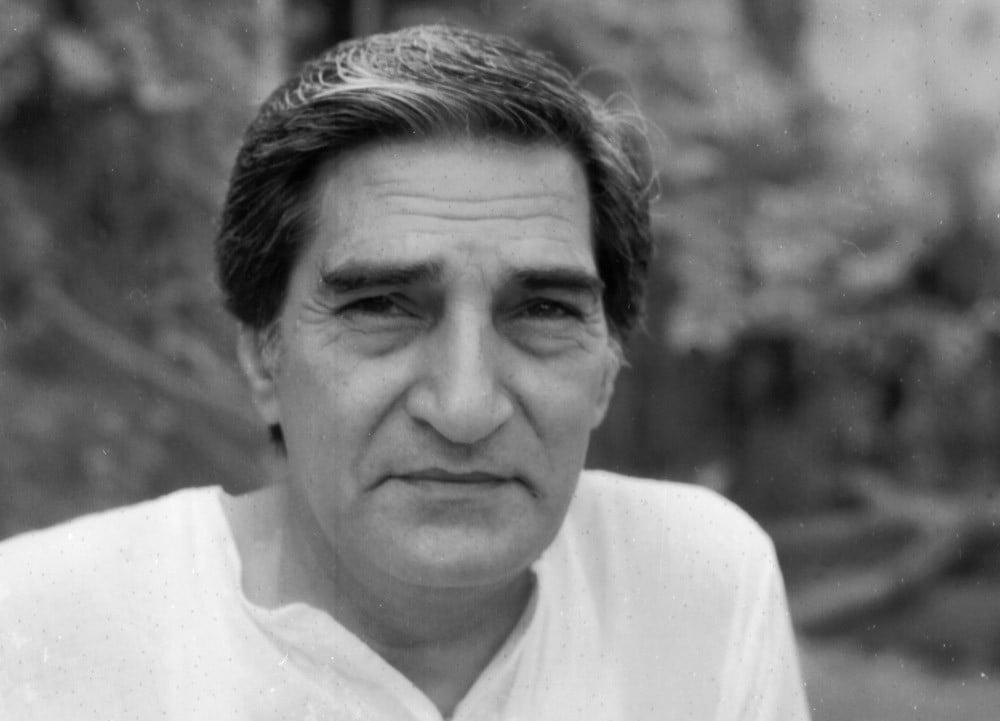

It is difficult to put Munnoo Bhai in any box but perhaps it can be said that he was a many-sided humanist; radical in his outlook on life, politics, and beliefs, and a friend of the underprivileged

It will be quite some time before we are able to assess, fairly and objectively, the life and works of Munnoo Bhai. In most of what has been said about him since his passing more than a week ago, the emphasis has been on the huge vacuum his departure has created in Pakistan’s journalism, its literature, its dramatics and its world of humanitarian activism. This does give us an idea of Munnoo Bhai’s multi-splendoured personality but we do not get a complete portrait.

What is attempted in the following lines too is a bare sketch, much more work will be needed to add to it appropriate colours and shades, and even to correct some of the conclusions.

Let us begin by acknowledging the fact that Munnoo Bhai was very largely a self-taught, self-made person. What made him choose whatever he opted for? Even when he let others make decisions about him - like Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi’s decision to change his byline from Munir Ahmed Qureshi to Munnoo Bhai or Aslam Azhar giving him 15 minutes to become a playwright - he had his own reasons to concur.

In his childhood he learnt to hate violence. Also he recognised love as the noblest life force. The desire to become a writer and a poet was born early in his life. His conscious life seems to have begun in Campbellpur, now Attock, where he was influenced by Dr Ghulam Jilani Barq, who had a rational outlook on religion, Professor Ashfaq Ali Khan, an aggressive Pakistani nationalist, and Malik Mohammad Jafar, a progressive politician and a keen upholder of the rule of law. For friendly company he had Shafqat Tanvir Mirza, the fiery campaigner for the rights of the Punjabi language, and Inayat Ilahi Malik, an early practitioner and promoter of the art of music.

The contribution that informal learning at Campbellpur made to his mental development can be seen in his later life choices. The desire to be a writer and a poet was confirmed; devotion to the mother tongue was consolidated, the path of rationalism in all matters was chosen, and love of fellow beings, especially the underprivileged, became the guiding principle.

It was difficult to put Munnoo Bhai in any box but perhaps it can be said that Campbellpur turned him into a radical humanist, radical in his outlook on life, politics, and beliefs, and a friend of everyone who was exploited or denied their lawful share of life’s rewards.

He began expressing himself in poetry and as a columnist. Poetry gave him a new name, Munir Ahmed Qureshi became Munnoo Bhai - a brother to all human beings - and columns opened the way to champion the deprived and the marginalised.

Munnoo Bhai was a natural and gifted poet. He didn’t have to labour on his verse. His poetry was mostly either a response to what he found ugly, wrong or odd in life or what appealed to him in the children’s artless way of reconciling themselves to a life of want and misery. He will be counted among the great poets in the Punjabi language because he enriched it with new themes and refined some of the themes it already held. And he had the ability to agitate sociopolitical matters without allowing his verse to fall to the level of agitational slogan-mongering.

Even a cursory look at the themes in Munnoo Bhai‘s plays will make his adherence to humanism clear, though his instinct for exploring the unusual also sometimes came into play. His decision to prepare a dramatic version of Shabbir Husain Shah’s novel, Jhok Siyal, indicated his desire to explore the layers of exploitation within an apparently simple and content rural society.

Similarly his Sona Chandi could be interpreted at many levels. Unfortunately, Munnoo Bhai’s career as a playwright was cut short by external factors; first he got involved with politics that he probably considered necessary and later, PTV closed its doors on him, and Munnoo Bhai moved on.

The real Munnoo Bhai will be found in his columns. From the very beginning he made it clear that his permanent theme was people and whenever he took notice of the high and the mighty and their doings it was to expose their excesses, their fads and follies and their encroachment on the entitlement of the underprivileged. His column became one of the country’s most popular, and in some respects one of the most effective platforms for the redressing the grievances of resource-less and voiceless citizens.

He could be more romantic than realistic sometimes but this didn’t detract from his mission to promote a culture of identifying oneself with the oppressed. I think he came to love freedom and socialism largely while searching for a means to end the suffering of the masses.

During the last decade of his life he quietly changed course. All his life he had been drawing generalised conclusions from specific symptoms of socio-political and economic mismanagement but in his final years he moved from the general to the specific case of thalassaemia victims and their right to life, cure and freedom from pain. This way he also ensured a perpetuation of his reputation for humanitarian work. A grateful Sundas Foundation named their upcoming hospital after him while he was still around - and so, he will be remembered by a hospital and not a mausoleum.

He deserves an epitaph like the one a poet had written for Tipu Sultan while putting his tarikh-i-wafaat in poetic form - Naan-e-bewa shikasta shud (The widow has lost her bread).