Don’t turn a child’s universe into a vortex of fear, instead give him the tools and confidence to report when something goes awry

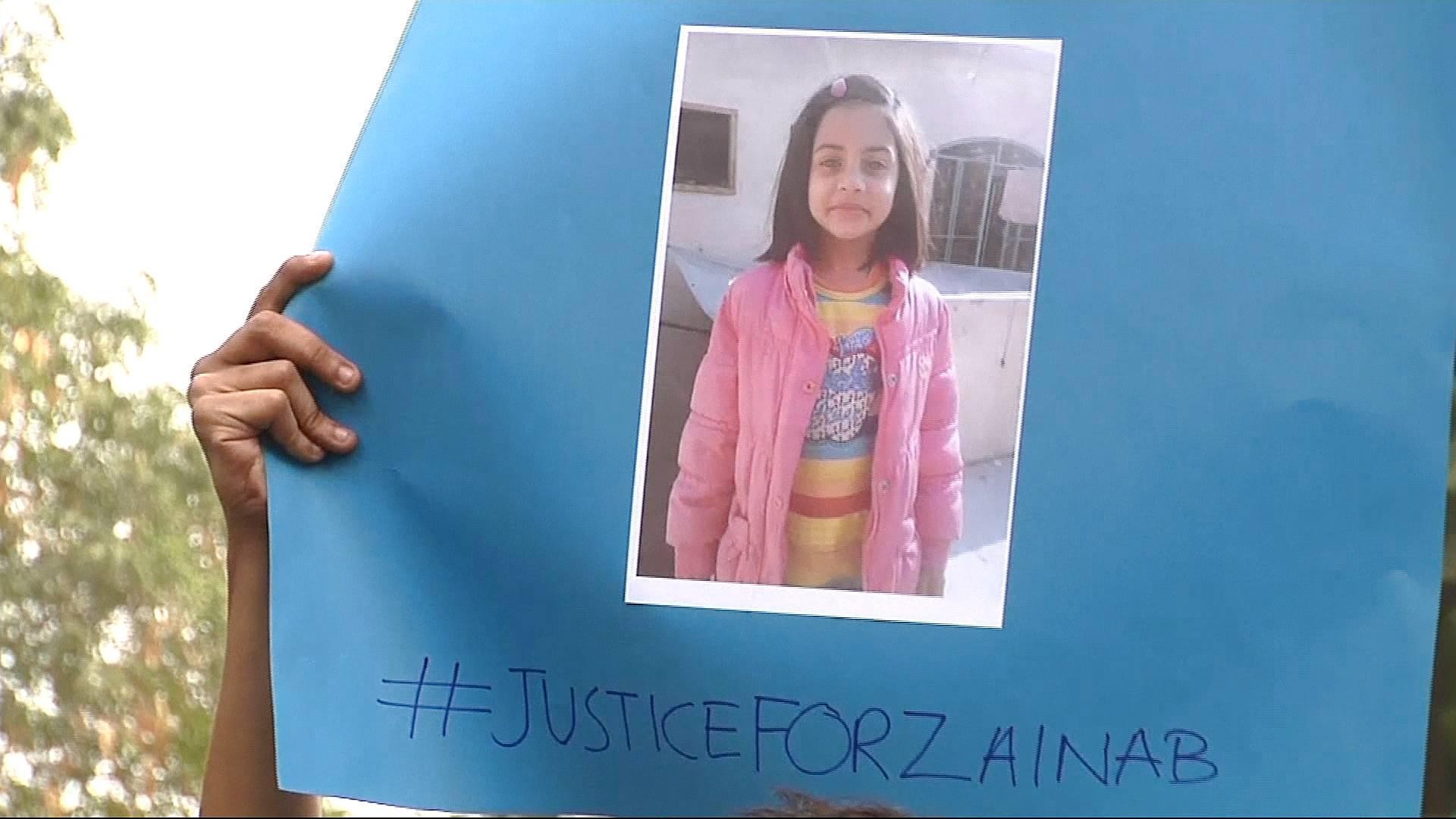

How should we talk to our children about sexual abuse? In the wake of the Kasur incident the answer to this tricky question has made its way to the horrified consciousness of Pakistani parents who have poured their hearts out on Facebook statuses, articles and television shows in the hope of never allowing another little girl to be made victim of such violence and terror.

Before I get to what can actually be done, let me state unequivocally what shouldn’t be. Wrapping a child in yards of fabric from the time she is able to crawl is not a way to prevent childhood sexual abuse (this is one of the remedies being suggested in widely circulated WhatsApp messages), neither is getting children married as soon as they hit puberty (one of my religious friends sent me a forward that advocated this approach).

Another text I received by a well-meaning friend listed a number of measures that could protect children from sexual predators. The first of these was to teach our girls that they have no brothers other than their own, ‘no cousin you call bhai is really a bhai,’ it stressed. ‘No child should shower or change in front of anyone, including you as a mother, father, sister, brother, khala, phuppo, etc.’

Another point insisted that ‘unnecessary communication with people around should be discouraged’. It also advised parents to sit their children down at the end of the day and ask them if someone had touched them inappropriately in the course of the day. I am uncertain how helpful this list of precautions will be in checking sexual abuse but admonitions of this sort run the risk of restricting a child’s physical universe to little beyond his immediate family (taken to its extreme conclusion even they would remain suspect), and runs the risk of discouraging natural curiosity and confidence.

Having children live in a constant state of hyper awareness is likely to create a generation of timid and suspicious adults unable to put trust in basic social relationships or the kindness of strangers, unable to ask for help where needed, and unable to create and sustain healthy social connections. However, burying our heads in the sand will only allow predators to get away with impunity and rely on the ignorance of their victims to continue to perpetrate crimes fearlessly.

How then should one strike the right balance between necessary safety awareness and crippling fear and paranoia?

Read also: Editorial

One of the things that has been talked about often is giving children the confidence to say no when it comes to their bodies. The concept of ‘good touch’ and ‘bad touch’ is also an important idea that has been discussed extensively. Instead of calling a certain kind of touch ‘bad touch’ though, it is best to teach children the concept of ‘secret touch’, one that is done in hiding and thus has a bad intent behind it, because sometimes even ‘bad touch’ can be pleasurable and can confuse children. A child should feel enough confidence in a trusted parent to immediately be able to report a secret touch to them.

While the role of the state is paramount in apprehending criminals who rape and murder, and in creating sex offender registries so that once caught a criminal cannot repeat a crime of similar nature, child sexual abuse is often carried out within four walls and doesn’t reach the level of reportable crime. Here the conversation between parent and child is of the greatest import, as is the vigilance of trusted caregivers. An involved parent can easily listen to a child’s cues regarding their feelings about a certain adult, and such intuitive understanding can reduce a general suspicion about the world at large.

Don’t turn a child’s universe into a vortex of fear and trepidation, instead give him the tools and confidence to recognise and report when something goes awry.