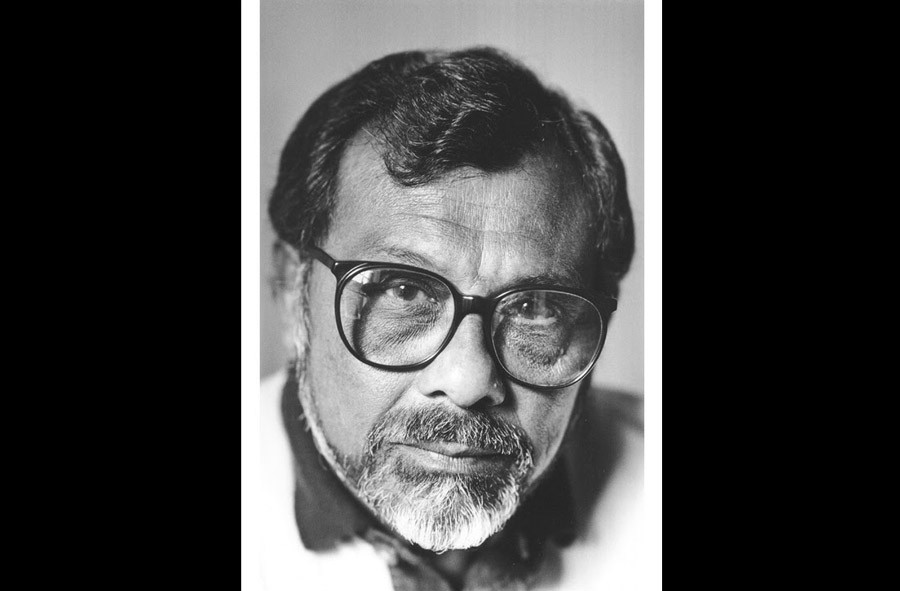

Ambalavaner Sivanandan, an activist-scholar, was committed to raising voice against discrimination on the basis of class and race

Ambalavaner Sivanandan, known to his friends as Siva, who died on January 3 aged 94, was an influential theorist, novelist, activist-scholar whose pioneering work on race relations and anti-racist grassroots struggle informed the work of a generation of thinking activist and campaigners. His passing marks the end of an era and profound loss of an original and fertile political mind.

Sivanandan was a brilliant political and organising mind, a decent human being and a firm believer in the third world liberation. At the Institute of Race Relations’ annual Christmas party, his had a lively, vivacious and stimulating presence. I fondly remember his enthusiastic help, guidance and an insightful interview for my thesis on family-led campaigns for racial justice in the UK.

Although he is not much known among the younger generation, he remains a giant among the old breed of anti-racist activists and scholars. His trenchant analysis is relevant to the current day struggles in both the UK and at global level as shown in his recent analytical work on the changing nature of market state, imperialism, globalisation and state racism.

From the very beginning Siva was interested in staking out a different position on racism outside of the established left position which sought to subsume race into the primacy of class struggle. Sivanandan took issue with the established left position that classless society would automatically lead to a raceless society.

According to Arun Kundani, ex-editor of Race and Class and author of Muslims are Coming, he believed that radical politics can only be built in the symbiosis between race and class. Arun further credits Siva with making vital contribution to the creation of a different black politics by opening intellectual and institutional space for this radical politics to mature. This Sivnadan did as the director of the Institute of Race Relations (IRR).

Sivanandan also founded an influential theoretical journal Race and Class which provided platform to anti-comical and anti-imperialist perspectives. This approach drew in activist scholars such as Eqbal Ahmed to its fold. Eqbal Ahmed also served as co-editor of Race and Class besides guest editing its special editions on the US and the Arab World, The Iranian Revolution and the Invasion of Lebanon. Eqbal Ahmed, as the director of the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam was also instrumental in helping the Institute in its initial days through fellowships and other grants.

Sivanandan did not author any major work but his political essays on important junctures in the British race relation history were widely consulted to shed light on the challenges and crises in the anti-racist and anti-imperialist struggles. These essays, later published in book form, continue to be read with avidity by anti-racist community groups and the wider public. His influence can be seen in the work of the Morning group, an anti-racist charity, as attested by a warm tribute paid by its founder Suresh Grover on the pages of the IRR.

Son of a poster worker, Sivanandan was born in Sri Lanka. He attended Ceylon University and went into banking after completing his education. A Hindu Tamil, he fled to England after anti-Tamil riots in 1958. He arrived in London at the time of Nottinghill Gate riots against immigration from the West Indies. This was what he called ‘double baptism of fire’ for him.

Like all Afro-Asian immigrants Sivanandan’s painful experience of racism saw him degraded into a lowly job as a tea boy in a London library. Yet Siva worked his way up and ended up as the chief librarian of the newly established Institute of Race Relations. This job was to transform Sivanandan in profound ways and mark out his future trajectory as an intellectual and activist. At the Institute, then funded by multinational corporations, focus of research was the objective study of race relations.

The purpose of the research, however, was to understand race relation in post-colonial Africa with a view to facilitating business investment. However, soon the fissure developed between the radical-minded staff and the management over pro-government orientation of the Institute in relation to the 1962 Immigration Act which drastically restricted

entry of the Commonwealth Citizens.

Disenchanted with the direction of the Institute, in 1972, Siva along with some radical members of the staff organised a coup against the management and took away the material and resources to a new office. The revamped Institute of Race Relations under his leadership, from thenceforward, was to become a research and campaigning organisation on race relation informed by the lived experience of daily racism by Afro-Asian immigrants.

The Institute provided space to community activists for reflection and organising thinking struggles to fight the state racism. The IRR has continued this important work through its regular educational and research work on black deaths in police custody, deportations of asylum seekers and racist attacks and killing. This important strand of work has consisted in documenting and analysing racist incidents and murders which feeds organically into new strategies of community resistance against institutional racism.

More importantly, Sivanandan played a vital role in propagating the notion of black politics among Asian and other communities. The black politics was informed by US civil rights and the Black Panther Movement. Siva famously said the colour of his politics was black. Siva also maintained that mass migration into the UK was linked with the imperial and colonial history and logic. He used to encapsulate this logic in the widely resonant phrase ‘we are here because you were there’.

A long-time student of English poetry Siva was fond of quoting TS Eliot and Gerald Manley Hopkins. The influence of English poetry also shows through Sivanandan’s graceful and plain prose.

At the age of 73 Sivanandan published his first and the only novel When Memory Dies which won both the Commonwealth Writers Prize and the annual Saga Prize awarded to first-time black writers. The novel is the saga of three generations of a Sri Lankan family and has been critically praised. This debut novel was followed by a collection of short stories titled Where the Dance which also received considerable critical acclaim.