Sana Kazi’s exhibition currently on show at Satrang Gallery, Islamabad is a deeply personal self-exploration of loss, dreams and mysticism

Is there such a thing as a dream of self-knowledge - of self-discovery, in which the self finds and experiences its reason for being? Is there such a thing as a sequence of dreams that track - with whatever meandering difficulties - the inner development from self-doubt to self-assurance - dreams of self-actualisation? This is the question that Sana Kazi’s dreams raise, and answer in the affirmative: they are dreams of self-fulfillment - dreams in which Kazi finds herself, comes into her own, makes her self real, with the aid of spiritual objects, that is, objects that have already found themselves and know their purpose in life, and thus are secure in themselves.

If dreams are narcissistic, they are radically transfigured in Kazi’s case: they are spiritual beings - autonomous selves that seem authentic, that is, self-possessed. Instead of being objects of desire, they become spiritual helpers; they guide the dreamer in his search for his own autonomous selfhood and authenticity - his spirituality and self-centeredness. They help him find a spiritual solution to his narcissistic ‘problems’, that is, they help him leave his old self behind and become a new one.

The father figure who appears in so many of Kazi’s works, currently on show at Satrang Gallery in Islamabad in the exhibition titled ‘Respite’, not only resembles the real father she has lost and mourns, but is the new spiritual father she looks to for consolation and advice, now that she has to stand alone. Kazi forms a kind of therapeutic alliance with this transcendental figure, who remains an enduring symbol of successful self-transformation. Consummate and convincing, Kazi’s identification with him permits her to gain her own identity. Artistic creativity, in her case, is the means of climbing to the peak of selfhood, and that her spiritual dream father encourages her to make art, as her own form of spirituality and self-experience.

The dream declares that the old self is not simply beyond repair but obsolete, and that a new self is necessary for psychological survival. Kazi’s works show her struggling to discard her old self to become a new self; her father’s death is the catalyst of the change, and her spiritualised father is its instrument. Instead of being buried out of the way - entirely expunged, emotionally as well as physically - Kazi buries her dead father deep within herself, giving him new symbolic importance and deepening her own sense of self, so that she comes to realize that she is creative. In an act of what amounts to spiritual cannibalism as well as love - for Stendhal it is a metaphor for the creative process - Kazi metabolises and assimilates her father, making him into a kind of sacred muse - the inner catalyst of creative action.

Sana Kazi immerses herself with Dionysian intensity in her material - even as she uses the figurative imagery of the religious tradition in which she was raised.

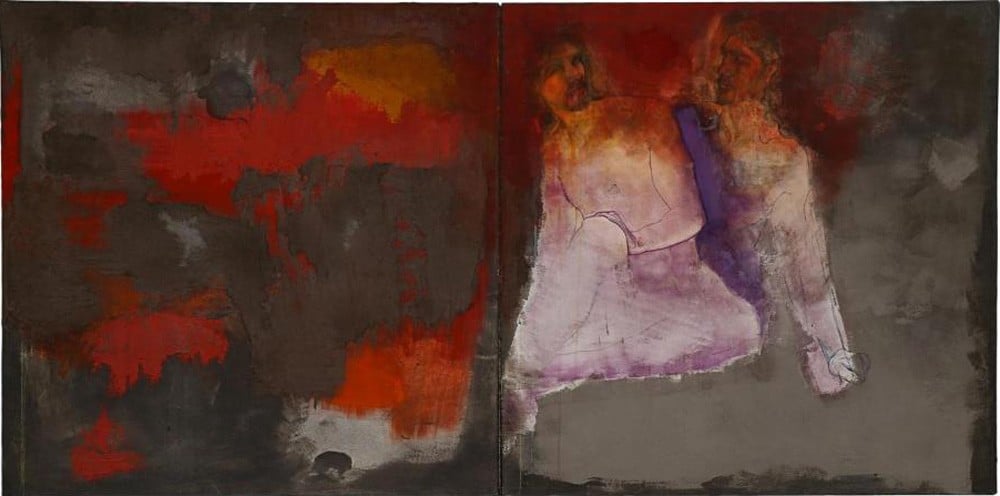

Kazi’s works have a strong sensuous presence. She dreams in colours and hears sounds, indicating the intensity with which she dreams. The sensuous immediacy of her work suggests that sense experience - sense experience for its own sake, independent of any meaning or as consummate in itself - is one of its themes. Sensuous contrasts suggest emotional conflict: the blue-grey landscape and atmosphere of Two Sanctuaries and Two Abodes is at odds with the deep red ground and white garments of Servant. The sheer presentational immediacy of Kazi’s dreams in Khwab Ka Aik Rang / Sub Khudi Se, for instance, confirms their visionary character, even as it gives them a peculiarly modernist cast, for all their religious character. The contrasts that constitute the immediacy are not simply symbolic of life and death but metaphysical in import, suggesting that sensuous immediacy is a higher end for Kazi, that is, has religious meaning. Another example in point is Yearn that illustrates the date palm bathed in golden luminescence that Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) used to lean against while delivering sermons at a mosque. When the Prophet (PBUH) took to the pulpit, the tree yearned for His touch.

Perhaps the most crucial theme in the entire oeuvre, along with the mystic guide, is that of crossing a threshold. Virtually every single work is about crossing over from one state of mind and selfhood to another. Each character in the work is caught in a reverie; in dreams of metamorphosis.

The work seems soaked with the strangeness that is trying to cancel time and space coordinates in order to create an anti-chronological, non-aesthetical setting in which the thin human condition can become visible.

While representing a subject, Kazi tries to purify the person, to erase all possible social identities, while at the same time leaving the important presence of a personal history. She is not interested in subjects as nostalgic personalities; they interest her as absolute entities that have become part of our collective memory. The notion of alienation may derive also from the way she represents the human face. Hands in her work are more in focus and recognisable than the faces. The human face has too many signs of self-expression and is too intimate, thus losing its link with more generalised reality and culture.

For Kazi that may have been a way to express her subjective stance - a way to create settings and situations that would illuminate the gap between imposed, produced subjectivity and a fragile singularity. Probably, that is where one is most likely to find parallels with the works of Dostoevsky and Kafka. Both volumes of paint and light deal with memory in her work, with the most honest representation or drawing of a memory intended as a symmetrical consequence of a desire. The selection process of the image is a crucially important part of her work, but the purification of the image during the process of painting is also of great significance.

Kazi’s journey has been her own; she’s employed all the languages of art - pencil, wood ash, ground terra cotta, copper alloy, dry pigment, desert sand, silicon carbide on wasli - in a continuous back and forth engaged with modernity but imbued with the past - rich with classicism but rooted in the future. Even her attentiveness to space and architecture is surprising: she is so passionate about exploring the essence of the spaces in which she hangs her work - the distance between things, the perspective, how energy circulates - so that she can find the right balance between light and shade.

For Sana Kazi the untold has the value of a statement; she traces a line that she consequently erases. She doesn’t like conventions and is indifferent to the rules of the system. Her approach is critical and meticulous, especially regarding linguistic stereotypes. She defines herself through rigour but at the same time has an indulgent way of looking at the world, which she uses at her own discretion: "What we need to measure is not the size of the canvas but our own memory. Art is a mental thing.’’