It is time to develop more robust and vital collaboration between archaeology and ancient history of Pakistan

It is rather deeply astonishing that history, archaeology and anthropology in Pakistan have not been able to bridge sheer disciplinary schisms. In other parts of the world, phenomenal developments have occurred in this connection. If archaeology and anthropology have walked alongside to the effect of deep mutual influence both in terms of empirical data and theory and methods, history and archaeology have also developed this type embedded relationship.

This state of affairs in Pakistan in relation to archaeology and history needs to be seen in its historical and contextual context. In the first place, it may be said that development of Muslim identity politics in British India, struggle for and, at last the creation of Pakistan, conditioned and determined the course of historical investigations in the country. Such political pursuits were in sheer need to be grounded in history.

Understandably, medieval history was the only available source to make fetish of. The spread of Islam, arrival of Muslims and their political control -- in terms of political and chronological articulations -- became identity markers. As a result, ancient history not only lost its value but started to go against the narrative of Muslim politics and identity. Thus an era of romantic medievalism began to prevail in the field of Pakistani historiography.

Second, in the wake of partition, ethno-nationalist considerations led to the creation of counter-official narratives steeped, again, in medieval and even modern times. Ancient history has scarcely appealed to the imagination of ethno-nationalist ideologues. Very few, and poorly constructed, episodic interests in this respect could be encountered in Pakistan. Dr. Shah Muhammad Marri has tried to locate Baloch ethnicity in the archaeology and ancient history of Balochistan. Similarly, G.M. Syed has boldly announced Raja Dahir as son of the soil and hero of Sindh.

Beside the ethno-nationalist romanticism, Prof. Ahmad Hasan Dani and politician Aitzaz Ahsan have vigorously made a case for adopting a longer view of history vis-à-vis Pakistan as a state and the process of nation building in the country. Both have objectified their articulations about Pakistan in a geographic sense i.e. the Indus land. Geographically distinct from the rest of the subcontinent, Pakistan has been experiencing cultural patterns unique and particular to itself. The pioneering protagonist of this idea, however, is Sir Mortimer Wheeler who authored Fifty Thousand Years of Pakistan (1950). This voice has not yet been heard in the power echelons of Pakistan.

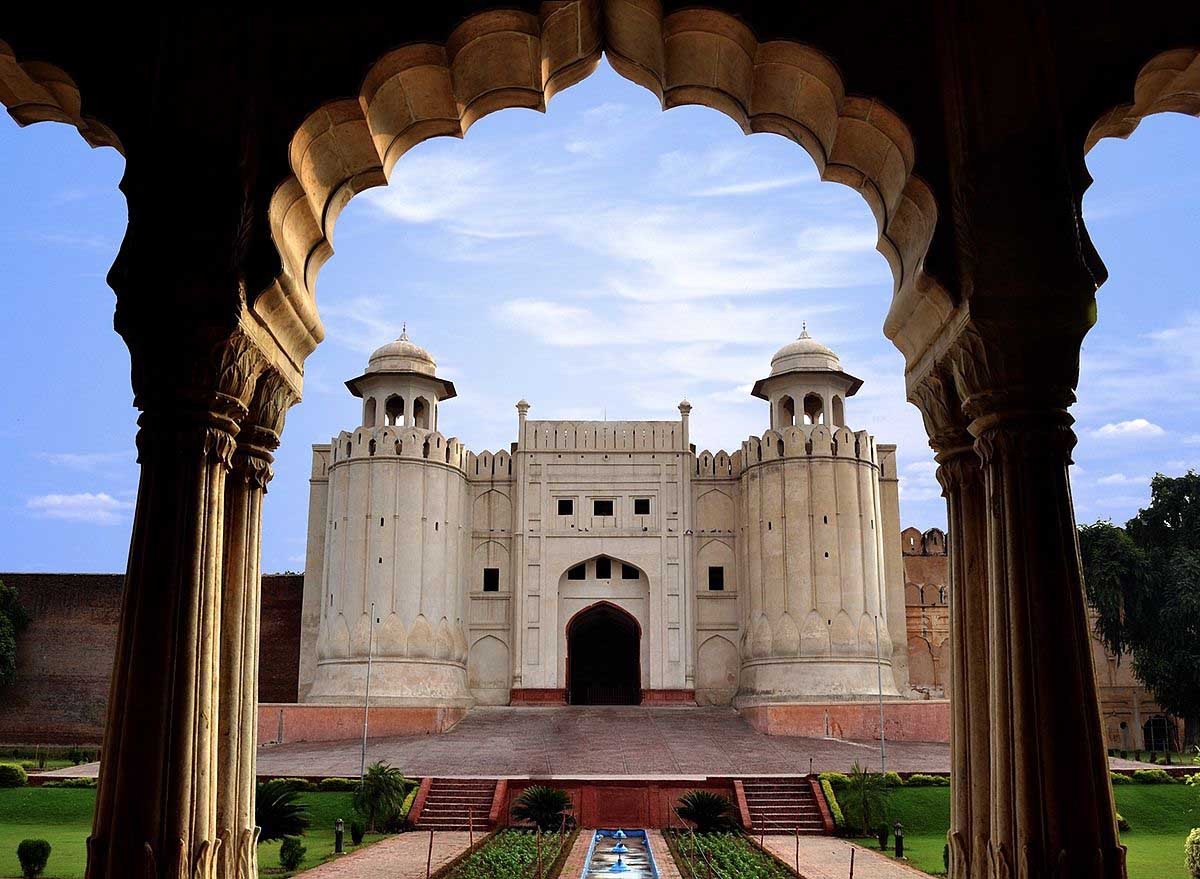

Thirdly, medieval history and culture is part of the living Muslim culture and memory. On the contrary, ancient history lacks this privilege. Sufi shrines, culture and literature serve as mnemonic devices providing impetus to medievalism in Pakistan. Similarly, medieval period art and architecture have also been visible to both popular and intellectual mentality. All this has not been without serious detriment to scholarship regarding ancient history in the discipline of Pakistani historiography.

Fortunately, however, archaeology has done creditable work and rescued ancient history from complete oblivion in Pakistani academic tradition. But the call of the time, still, is to develop more robust and vital collaboration between archaeology and ancient history. And the ultimate aim shall be to attain a fruitful theoretical and empirical integration.

In Pakistan, archaeologists and historians can hardly appreciate each other’s work. It is due to the fact that both the sides work in isolation and in nearly complete separate domains. Departments of history almost lack any programme and workable mechanism in relation to teaching and research in ancient history. Keeping in view this situation, I would like to suggest that there should be extensive and intensive contacts and collaboration between archaeologists and historians and their respective departments. In each programme shall be included some fundamental courses from the other one. For the discipline of history may be suggested courses such as archaeological data and its interpretations (which shall focus on what archaeological data is, how is it obtained and how to explain and interpret it), ancient societies and cultures (their historical and civilisational studies) and ancient history and archaeology of South and Central Asia (starting from around 10000 years before present till the beginning of the last millennium). It will, at least, orientate students of history to the field of ancient history and the interested ones would be able to pursue career in it.

At the moment, it is heartening to note that the Department of History at Allama Iqbal University, Islamabad, in the dynamic leadership of Prof. Samina Awan and VC Shahid Siddiqui, has timely appreciated the need and importance of ancient history. So far, a comprehensive course on the ancient history and historiography of Taxila -- with a vivid emphasis on its archaeological framework -- has been developed for inclusion in the BS Programme. Prof. Samina is also thinking about doing more in this connection.

On the hand, in the studies programme of archaeology, it is advisable to introduce students to methods of historical research, historiography, cultural and intellectual movements and thoughts in the modern world and European colonisation. All this will enable archaeologists in the making to get familiarity with the origin, development, science and politics of their discipline.

The result of all this seems to be a productive intimation between archaeology and history. It will enable both archaeologists and historians of Pakistan to know the exploration, investigation and politics of archaeology and ancient history during British India and after the partition. This understanding has been stronger enough in India and in the West. All historical and archaeological investigations have been informed by these considerations. Pakistan shall also make its presence felt in the field of these discourses and narratives.