Muhammad Umar Memon translates two French chick-lit novels into Urdu, allowing readers a peek into a different time, an awkward place, a strange people

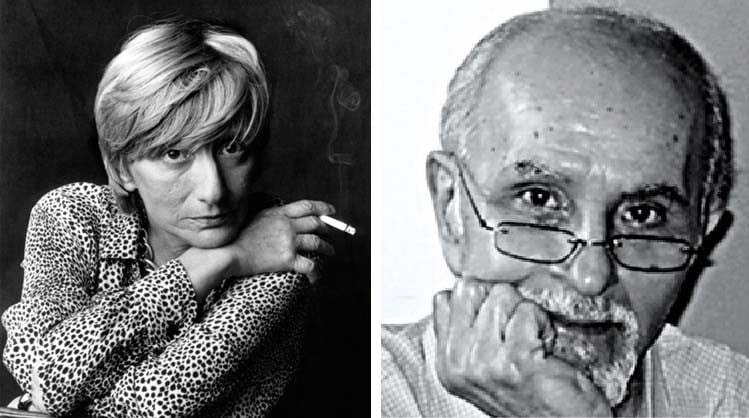

Notwithstanding Z. A. Bhutto’s cruel joke about turning Lahore to Asia’s Paris, what can French author Francoise Sagan’s two slim novels translated into Urdu by Professor Umar Memon offer to the Urdu world? Before we explore that question, perhaps we should first ask the question: why translate?

Un certain sourire, (1956) takes the form of direct speech by Dominique, a young provincial woman studying in Paris, in a relationship with a young Parisian, also a student. Her partner introduces Dominique to his maternal uncle Luc and his wife Francoise from the upper echelon of society. If the novel on the one hand is about the affair between Dominique and Luc, the middle-aged uncle, it is also about two relatively free spirited persons who prefer pleasure, love, sex, adventure and drinks over boredom, conformity, guilt, and loneliness.

Since the novel, translated into English as A Certain Smile and into Urdu as Kuch Aur Si Muskurahat, operates from Dominique’s eyes and ears, what we know of Luc is what Dominique allows the reader to know, that this is not the first time he has seduced someone, nor will it be his last extra-marital affair. This is despite the fact that he loves his wife in a certain way and shows concern that his behaviour hurts her. As far as he is concerned, c’est la vie!

But Francoise has also become a mother figure to Dominique, and here the protagonist has to deal with guilt or rather a dilemma, moral or cultural. Francoise finds out and the two women meet in the most elegant and civilised fashion, in a way only the French can. Dominique apologises for her betrayal and Francoise shares her deepest fear of not being young anymore. "It was silly of me . . . I knew perfectly well that what happened between you and Luc was nothing serious . . . I mean that unfaithfulness of a physical kind doesn’t really matter. But I’ve always taken it hard, and particularly now . . . now . . . that . . ."

She seemed to be in pain, and I was afraid of what she might say.

"Now that I’m no longer so young," she went on, turning away her head, "nor so desirable."

"No," I said.

Francoise tells Dominique that she is very fond of her. Days and weeks go by, and one day when Dominique is listening to Mozart, she returns Luc’s phone call. He asks her out for a drink. She says, "Yes, yes". The novel ends on a complex note as she tells the reader: "I was alone. Alone, alone. Well, what did it matter? I was a woman who had loved a man. It was a simple story."

Les merveilleux nuages (1961) is the second novel, it has been translated into English as Wonderful Clouds, and Hairati Badal in Urdu. The story is about a French woman married to an American man, born and raised in Florida and now living in New York. It is tempting to label the wife as unsympathetic, self-obsessed, melancholic, spineless, someone who wishes to regain possession of herself by occasionally sleeping with other men to complement her husband’s neurotic jealousy. The husband comes across as pretentious, controlling, and contemptible; he hires private detectives to watch over his wife’s daily excursions to report back to him.

But it is also a tale of two rich, spoiled, people who love and hate each other and yet don’t know how to separate gracefully without inflicting emotional wounds. The seed for Wonderful Clouds had already been planted in the opening of A Certain Smile, when Dominique tells the reader that Bertrand cannot allow her to be happy independently.

A little context is in order. Sagan’s prose emerged on the French literary scene when society was itching for change. Starring in Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman, Brigitte Bardot had exploded onto international screens, paving the way for the new unselfconscious woman. Between the publishing for Sagan’s A Certain Smile and Wonderful Cloud, Louis Malle’s 1958 films Elevator to the Gallows and The Lovers had given the Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) cinema movement its queen: Jeanne Moreau, even before the movement had actually begun.

Chabrol’s Les Cousins, Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, and Godard’s Breathless announced the arrival of the French New Wave cinema. Casting American actress Jean Seberg in Breathless was a self-conscious act by Godard as he recreated the image of a modern woman inspired by Sagan’s novels. It is no coincidence that Jean Seberg played Cecile, the lead role, in Bonjour Tristesse, a film based on Sagan’s first novel.

The New Wave introduced fresh prototypes of young French women, unburdened by old moral values, in part as a reaction to the destruction inflicted by WWII upon the French psyche, not to mention the anti-colonial sentiment all over the world against the colonial, patriarchal, and nationalistic European culture. In short, for all sorts of complex reasons, there was a new French woman, partly a construction of male desire, who was free to roam and navigate the streets of Paris.

In both of the novels that Umar Memon has translated for the benefit of the Urdu reader, the protagonists Dominiqie and Josee are caught in a struggle to learn to be happy, independent of men in their lives with an undercurrent of existentialism. It is this aspect that connects the two novels to women and women writers’ consciousness all over the world at that time -- during the second wave of feminism.

I am glad and thankful that Prof. Memon translated Sagan. Every new addition of translated literature -- even French chick-lit as these novels are -- enriches the world of Urdu, allowing readers a peek into a different time, an awkward place, a strange people who might resemble us but are not like us. They are not us in terms of culture, manners, history, moral sensibility and yet somehow we can detect the echo of their voices and actions in our dreams. That is why it becomes essential that the translator pays utmost attention to the cadence of language, the register of speech, the shade of thought.

It is with this in mind that I found that Prof. Memon’s choice of words, at times, especially in A Certain Smile, belies the essence of Sagan’s prose. What lends her prose power is the sense of urgency, something written in a rush, a bit pedestrian, eloquent perhaps but not literary, that it touched a nerve in the same way as J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye (1951) had done. Salinger, however, was 32 when he created the pitch perfect register of a male teenager’s inner commotion. Sagan, on the other hand, was barely 20 writing as a 20-year-old would. The pitch and tone recreated in Hairati Badal feels more in sync.

For my personal taste, I would’ve preferred words from Urdus rustic stock as opposed to the velvety sounds of Persian and Arabic in several places. It is possible that many of us have internalised that French sounds are more musical, philosophical, intellectual, literary and elevated, even when they are not.

As a reviewer, consulting the English translations doesn’t help since Prof. Memon has pointed out in the introduction that there were areas which he found problematic. When he consulted the original French, he made changes independent of the English translations. The Urdu reader is lucky to have a translator in Umar Memon who can, while translating, access the original besides English. If one were to count the foreign novels translated into Urdu in the last 10 years, I think the bulk of it represents male novelists. Introducing Francoise Sagan to the Urdu reader begins to correct that imbalance to a certain extent.