On reading Amit Chaudhuri’s seventh novel, which is a prism that refracts writing into multitudes of possibilities, a novel by a novelist who believes he doesn’t write novels

I meet Amit Chaudhuri at an event in London, where he is to speak ‘On Inspiration’. Here, we are also to get a glimpse of his artwork, a photo exhibition of ‘The Sweetshop Owners of Calcutta’. As always, I am already there long before the opening time and wait for a little more than half an hour for the gallery to open. On entering the room where the talk is supposed to take place, I see a mini-stage set up with mikes, speakers and tangled wires. He makes us listen to his songs and talks about composing them, he tells us about his first CD called ‘This is not Fusion’ and chats a little now and then, sometimes humbly, as if saying ‘thanks for listening’ and sometimes sincerely, with a sense of achievement, saying the same thing.

At one point he says "I am often not sure about what I am doing, so I ask people. I ask my wife, is this right? What I am doing, should this be done?" or something like that. Memory is fickle but we invent to narrate. After the event, he is ready to sign copies of his latest book, Friend of My Youth. I speak to his wife, Rosinka, for a while. I am interested in her work and in talking to her. We plan to meet next week. Then I drift towards Amit and he comes up to sign the copy, thanking me humbly for coming. He asks my name, how it’s spelt and on hearing me spell it out, nods and says "So the usual way". I think not, but have many other things on my mind. I tell him a little about what I do and he listens kindly, earnestly. He gives me his email and tells me I can write to him. We thank each other again, without any pretences and I leave soon.

I already feel like I have known him for a long time.

I begin to read the book but something prevents me from turning the pages. I am a lazy reader. Slow. Distracted. Lazy. But this book doesn’t move! What is the point? I leave it. I do other things. I don’t like the jacket cover. It looks like milk spilled on a photograph. I rid the book of the cover and am pleased at the stark crimson binding beneath. I begin to read again. It is not easy. I start craving for something I cannot put my finger on.

I write to him asking if we could meet and he replies in the positive. I think of finishing the book before the meeting but this is not to be. I am spending more time with it, now comfortable that the book is a mysterious, red ‘thing’ that I feel comfortable carrying around. I am not conscious of reading it in the halting, warm tube to the library and back. I even begin reading it while standing in queues, when I take a break to smoke a cigarette and have to leave the pub. I read it inside the pub as well, and start noticing a curious shadow on a half-printed page. Light from a nearby lamp travels through my glass of golden cider and refracts into multitudes of hemispheres of fragile shadows. They overlap each other at innumerable trajectories, forming an intricate web, threatening to shatter at any moment. I feel a little light headed. It’s the image, I’m sure. I take a picture and send it to a friend. He responds: "Imagine pages of a book with similar texture". My head starts to reel.

Amit’s seventh novel, Friend of My Youth, is a prism that refracts writing into multitudes of possibilities. It is a novel by a novelist who believes he doesn’t write novels. And yet in this auto-fictional (not autobiographical) narrative, the narrator who is writing a similar book, confirms that what he is writing is definitely a novel. "The book is a novel. I’m pretty sure of that. What marks out a novel is this: the author and the narrator are not one. Even, if by coincidence, they share the same name. The narrator’s views, thoughts, observations -- essentially, the narrator’s life -- are his or her own. The narrator might be created by the author, but is a mystery to him. The provenance of his or her remarks and actions is never plain."

The narrator is an Amit Chaudhuri, travelling (not just once) to Bombay, where he spent much of his youth and childhood. He is on a book-related trip but then he goes back for a holiday with his wife and daughter. This Amit Chaudhuri is also writing a book. He writes of his school days, of his friends, of the detachment and enchantment of growing up in and with the city, of old habits and recent changes, of his mother and her taste in shoes, of the Taj Hotel, before and after the terrorist attacks, of boredom, of interest in the lives of others and one’s own, of ennui, of everything and of nothing. Reading this book becomes an immersive process, not so much into the book but into all that it provokes and projects as you continue to read. The narrator and the author do not necessarily bifurcate into two separate entities -- they create a sense of depth through layers of intimate juxtaposition.

Hilary Mantel compares Amit Chaudhuri to Proust for "perfect[ing] the art of the moment". Magnifying the most ordinary, he takes us on a journey in search of time -- lost, passing, and hanging heavy, while slowly, by repeatedly showing us the beauty of magnified everydayness, the narrator becomes a friend of the reader’s youth. Ramu, the narrator’s friend is not just a literal friend. He is that intimate ‘other’, on whom we project our sense of the ‘self’, who, through difference, allows us to be comfortable in our doubts and confidences. Ramu is not nostalgia but an adjusting presence that unites the narrator, the author and the reader. Ramu is what makes the novel possible. And yet, Ramu is much larger than the novel. The narrator tells us, "I suddenly grew tired of the novel…Does every experience I have need to be addressed by this one form?"

This is not a book about writing and yet, a reader has much to learn from it. It is a book that plays with the "difference" of the reader and the writer, that Amit discusses in D. H. Lawrence and Difference. I had read once, that "Nothing happens in Amit Chaudhuri’s books". Fiction is almost always burdened with too much of ‘happening’, almost providing for an escape from our mundane reality. Amit topples these boundaries to make us think of fiction, not as an escape, but as tricky as life. One of my favourites is the time when Amit and his parents, in search of good Parsi food, "set out on that nearly hour-long journey", "from Bandra to RTI, charged with anticipation for kid gosht and dhansak" only to find out that the "place was closed". He finely weaves the quotidian and the banal with the grandeur of anticipation and anti-climax. To do this he uses a humble but sly, stealthy humour, that is essential to the journey of every individual, their detachment and enchantment with certain temporary and permanent milestones.

Amit takes the reader around, walking in the city, down the lanes of memory and back to the alleyways of consciousness, slowly revealing the possibilities of life, "happening". Chaudhuri’s fiction lingers on the significance of all that is seemingly insignificant to be written about and this is its great significance. Deconstructing what ‘fiction’ has come to mean in our world, he is perhaps, as Terry Eagleton has pointed out, a most sensible writer, because he is a sensitive critic. In writing, he reconstructs the relationship between literature and life. "I live. Then something prompts me to write. The writing is not about life. It is a form of living. The two happen simultaneously." Reading this book is a "precious wastage of time". And is that not the point of life and literature -- to identify, question and subvert the value of things, most of all time, and to acknowledge the necessity of wasting this preciousness?

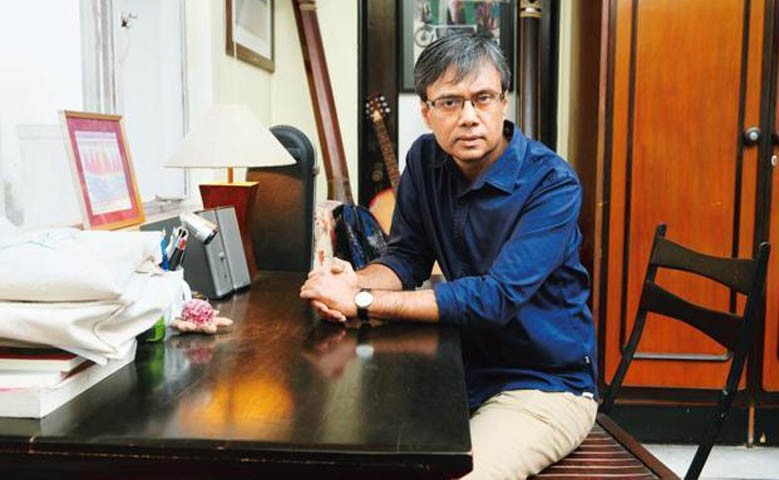

I meet Amit this evening. I try, as usual, to reach before time only to see him, already standing on the café level in Foyle’s. Clad in warm clothing and muffler, the quintessential Bengali who looks like the narrator of the book, he smiles in recognition. We drink coffee and chat about ‘doing nothing’, which happens to be common to both our respective work topics. None of us mention his latest novel. Amit stays back to look at books. I leave. It begins to drizzle.