Pakistan People’s Party has defined the country’s political aspirations for a quarter of a century. This may be an appropriate juncture to review its journey and identify the party’s prospects

Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) turned 50 this week. It was on the last day of November 1967 that a small group of ebullient political leaders (mostly unknown) and workers (mostly young) gathered at a dilapidated Gulberg bungalow in the city of Lahore to form a political party. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) was chosen as the leader of the new party. Bhutto had been the foreign minister under Field Marshal Ayub Khan, the very dictator whom the new political party vowed to take down.

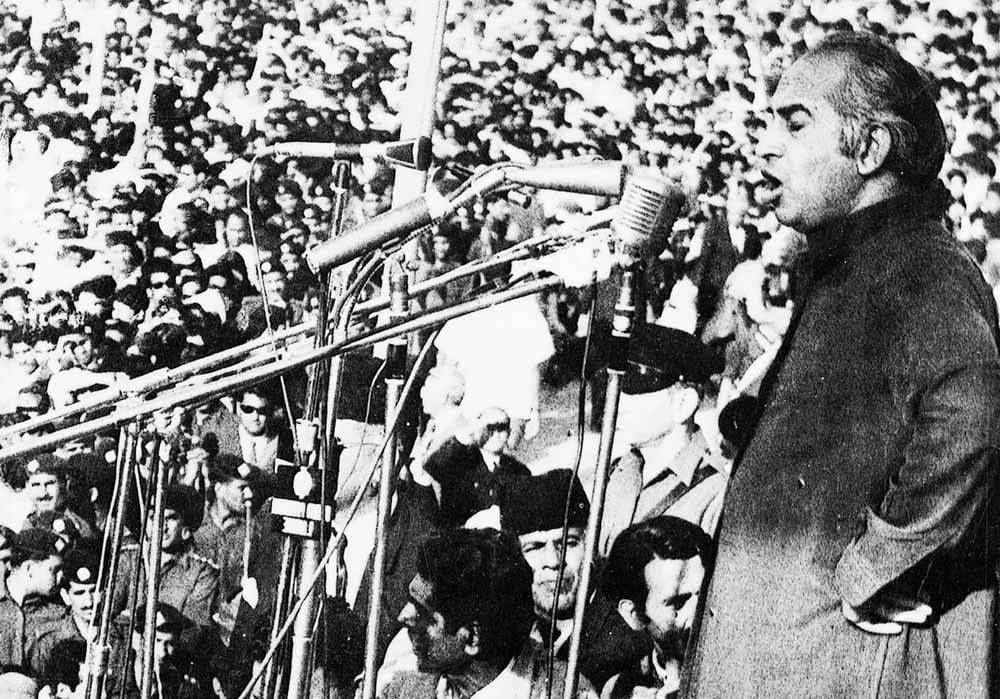

Bhutto was steeped in the image of 1960s dream generation. Equally comfortable with the powerful across the globe and the have-nots at home, Bhutto was a sophisticated thinker, an astute political mind, and a passionate speaker with a pronounced egalitarian socio-economic posture.

Those were the days when the midnight children in Asia and Africa were beginning to question the fruits of national liberation won by their parents’ generation. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, an anti-US tilt was in vogue among the young people. Bhutto raised the flag for the people’s power and a democratic dispensation. However, he also added the socialist tint and a dash of religiosity to the populist cauldron of his politics. Democracy, Islam and socialism were to define the PPP for the next several decades.

From 1970 to 2017, ten national elections were held in Pakistan and the PPP emerged as the most popular party in the country a record six times. It was no small success in a country perennially hounded by prolonged military dictatorships, dotted with periods of behind-the-curtain conspiracies, self-made crises and hand-made political puppets. The PPP has defined the country’s political aspirations for a quarter of a century. This may be an appropriate juncture to review its journey and identify the party’s prospects.

Let us first look at what the party has given us. The PPP can be credited with creating the culture of people’s participation in the political process. Politics in Pakistan, back in 1967, were the anointed secret play of the feudal lords, stuffed bureaucrats and baton-carrying Bonapartes. Under the dynamic leadership of ZAB, the PPP rallied the masses, the poor and the working classes around its tricolour. It taught the man in the street and the woman in the house to link their fate to a certain political affiliation, to cast their fate with a leader and to create a bridge of trust with a political plank. The shirtless and the shoeless of the land would rock to the chants of hailing Bhutto to live long and lead the country.

Never before or after that fateful day in December 1970, did a tiny piece of paper, the vote, assume such serious significance in the annals of our country. The faceless voters handed Bhutto and his party 81 out of 138 National Assembly seats that were up for grabs in West Pakistan. The 1970 election also foreshadowed the break-up of Pakistan. The events of 1971 had a certain historical determinism rooted in the geographic, economic, cultural and administrative features of the Pakistan that was established in 1947. PPP, being a major political stakeholder, could not dissociate itself from the dismemberment of Pakistan. However, if names must be given to the Dhaka debacle, the names of Yahya Khan and other generals would top the list who had been ruling the country for the previous 13 years.

While it is true that ZAB didn’t protest the actions of the ruling junta, to hold the PPP responsible for the separation of East Pakistan is fallacious. Had the PPP enjoyed the power to do so, it might have saved the life of its own founder and leader, eight years later. In fact, the PPP took up the unenviable challenge of steering what remained of Pakistan.

The drafting, consensus approval, and promulgation of the 1973 Constitution is the single-greatest achievement of the PPP and its leadership. The 1973 Constitution is the rudder that the federation of Pakistan has been plying for the past 44 years. Even two military dictatorships could not must the muscle to abrogate the constitution. However, the persistent manoeuvres to mutilate the parliamentary democratic character of the constitution testify to the unease that the undemocratic ambitions feel with the constitution. Hence, the PPP can draw enduring credit for furnishing the country with the fundamental law of the land.

During its first tenure, the PPP committed several mistakes. The nationalisation of industries and businesses was an ill-considered policy and shook the business classes’ trust in the PPP for ever. Ironically, it strengthened the hold of the dysfunctional bureaucracy instead of the intended well-being of the poor class. The nationalisation initiative earned the tag of bad governance for the party. The PPP has never established its credentials for effective management and sound governance practices. The failure of nationalisation tore down the socialist veneer of the party and critically discredited the left-wing leadership and the cadre.

Looking back, some analysts suggest that ZAB had added the socialist plank to his party’s repertoire only in the hope of winning some easy popularity at home and in the larger international picture. The negative fall-out of nationalisation allowed Bhutto to shun the pretence of socialist ideology and embrace capitalist economy with its ancillary components of religious bigotry and social conservatism in the Cold War context.

The PPP aspired to an enlightened façade without really alienating the deeply conservative populace. The party had included religious lexicon in its founding documents. Further, the separation of East Pakistan under the flag of a secular political leadership also reinforced the impression among the ruling elite that Pakistan post 1971 needed a heavy dose of religious identity. A mere few dozen national assembly members of the religious right virtually dictated the fundamentally flawed constitutional scheme that conflated state with faith.

Bhutto believed that he could camouflage his notions of modern statecraft with seemingly innocuous religious diction. He was wrong. The religious right proved too uncanny to allow any space for an enlightened, non-discriminatory and an equitable polity. The Second Amendment to the constitution, again, perhaps emerged from populist ambitions. The coming years proved beyond doubt that the political Shylocks of Pakistan were in no mood to concede their pound of flesh.

Come 1977, and the PPP was badly bruised through maximalist interpretations of the constitution, law and the political discourse.

Another major mistake by the PPP in its first tenure was to seek nuclear capability without securing democratic posts. The party wanted to fortify its nationalist credentials through an overreaching security narrative. It only allowed its opponents to label the party leadership as a security risk in the coming decades.

1979 marked the saddest and the most redeeming chapter in the history of the PPP. Its founding leader was sent to the gallows on trumped-up charges of murder. There is strong evidence that Bhutto could have saved his life by surrendering his political career but he refused point blank. This triggered a history of resistance against an entrenched establishment by the party.

Under Benazir Bhutto, the party relinquished its quasi-socialist stance and social enlightenment. The party garbed itself in a pretended social democratic cast without any concrete features. The party continued its pro-federation politics even as its leadership was slaughtered with a shattering consistency. The PPP did a great service to the country by blunting the edges of the fissiparous nationalist politics.

Asif Ali Zardari pleaded the federation of Pakistan while literally shouldering Benazir Bhutto’s coffin. No other political party has endured a dual attack from the military establishment as well as the fundamentalist clergy, longer than the PPP. That the PPP was a signatory to the 2006 Charter of Democracy (arguably the second most important document after the constitution of the country) adds lustre to its illustrious inventory, and that the party was able to elicit consensus around 18th Amendment to the constitution proves its political acumen.

The PPP has suffered from some really glaring pitfalls; this is not unusual for a broad-based popular political party over the course of half a century. The PPP is not above power politics; in fact the party suffers from what some analysts tag as "power haste". The PPP has not overcome its desire to flirt with the political right and garner some avoidable mistakes on the way. The party is also accused of carrying its anti-America posturing too far. Facing the relentless onslaught of anti-democratic forces, it is convenient to place some of the implacable crises at the doorsteps of a conveniently distant global power.

After nearly four decades of political struggle as ‘outsiders’ in the political arena, the PPP has consistently lost both political space and popular imagination. The average PPP workers as of now is safely above 60-years-old, that’s a real challenge in a country with the median age of 22.6 years. The political frontlines in Punjab, the biggest province of the country, have been overtaken by new entrants to the game.

The vital linkage between the PPP and its programme has been badly damaged. However, it is unlikely to vanish from the political map of the country any time soon. In fact, if this party can successfully blend the untarnished energy of its leader, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, with the upright moral stature of his two sisters, Bakhtawar Bhutto Zardari and Aseefa Bhutto Zardari, the party has the capability of bouncing back to its legitimate share of political power.

The critical test for the PPP, however, lies in its ability to sustain the spirit of the Charter of Democracy while wrestling with the ghosts of power politics in the country. The PPP supporters are thankful to the party for what it has done in the past and look forward to a democratic future where two or more political contestants try their political skills in a level playing field.