Maybe, at 70, we are finally young enough to try to understand Pakistan’s unsettled histories

This year, Pakistan turned 70. The young nation is not so young anymore; and as the last generation to remember its prehistory disappears, the country is quickly approaching a full life span of its own. To map the life of the nation, one could draw its histories like lines on a page. Taking 1947 as origin, you could trace trajectories from a multitude of sites, each trail its own teleological thread. Paths with their own twists and turns, perhaps, but ultimately reaching the same final destination: the here and now.

What about the places, though, that these lines do not cross; quiet towns on the periphery, far from the roads of historical event? How do we map the memories that exist outside of time?

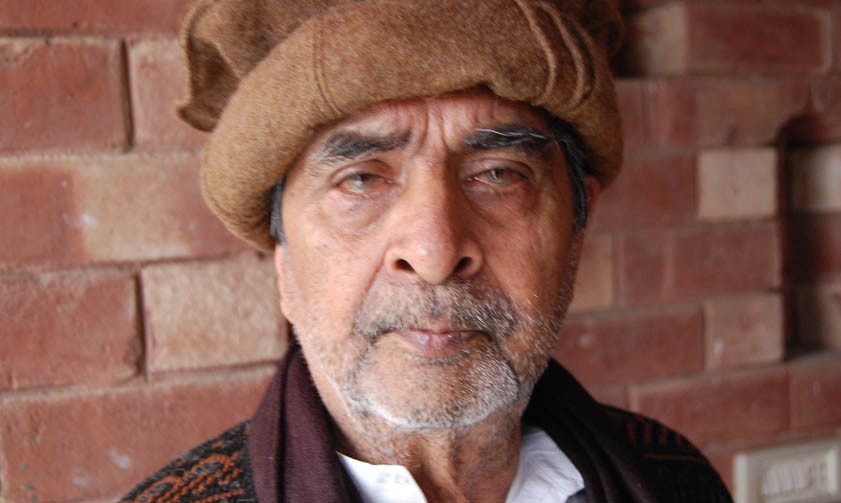

On this particular anniversary of Pakistan’s independence, I was aimlessly scrolling through news articles when I came across something unexpected. It was an obituary for Jamal Naqvi -- prominent Pakistani professor, political worker, and communist leader -- dated August 4th. He was 85.

I met Professor Naqvi for the first time in 2012, at his home in Karachi. I was working on a project on the history of left-wing student politics in Pakistan. It was a hot summer day in June; the humid Karachi air hung heavy around us as we sipped rooh afza under the ceiling fan. I asked him about how he had felt about leaving his hometown of Allahabad to come to Pakistan. He looked at me tiredly. "I was disappointed, at the time. And as time has passed, my regrets of leaving my own country have only increased. It is just a story of disappointment."

Naqvi migrated to Karachi with his family in 1950, not as a refugee, but as a young Muslim migrant, following the promise of a better life in the new nation. "I had never seen a port city before," he told me. The dry hills and sea views of Karachi were nothing like the plains of Uttar Pradesh. "I had never even seen a hillock…This city was very different. I went to the place we were living on a camel cart." They settled in PIB Colony, a new locality constructed for the influx of immigrants coming to the city. Naqvi took admission at Islamia College, where he studied English, and became involved in leftist politics.

The platform from which Naqvi and other like-minded students (many of them also immigrants from India) developed their political consciousness was the Democratic Students Federation (DSF) -- an organisation formed in Dow Medical College in 1950. Originally oriented toward local academic and economic issues (such as lack of transportation or the cost of student healthcare), the group began to take on political dimensions as it rapidly grew. Within a year of its existence, the DSF was sweeping student union elections across the city. "We had one highly political demand -- and that was, employment to all," Naqvi explained. "Our opponents, the Jamaat-e Islami students, hammered us on this -- that this was a point of the communists. And it was."

The DSF, before it was banned as an official "front" of the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) in 1954, developed into a real organ for the voice of middle-class youth in the nascent nation. Their activities and protests reflected a consciousness that extended beyond the world of college and community, family and nation. They read Mao and Lenin in their study circles; during the Suez Crisis, they held anti-British protests on declared "Egypt Days." When the party was banned, Naqvi heard the news from a radio while sitting at his usual tea-stall in PIB. That evening, he was arrested under the Security of Pakistan Act, and taken to Karachi Jail without a struggle. "Yes, I saw it coming." He remembered the event mildly. It would only be the first of many prison sentences for the young communist.

Driven underground, the CPP activity was severely disrupted, and only found an outlet again with the rise of the National Awami Party (NAP) in the late ‘50s. In 1960, Jamal Naqvi was assigned to be the liaison person with the CPP’s counterpart in East Pakistan. Over the course of the next decade, he would make over 40 trips to Dhaka -- a tempo which, as he put it, outpaced most government ministers.

The trip cost 250 rupees, and each time, Naqvi would stay in Dhaka for a few days. He remembered its geography, so unlike that of Karachi: lush and green. "There are so many vegetables there which we don’t get in Pakistan," he remembered suddenly, as we were talking. "I remember one of them: parwar. Have you heard of it? It grows on a vine in a lake type of place. It’s a small fruit, and they would fry it in sarson (mustard)…I liked it very much, and I would ask my host in Dhaka -- cook parwar!"

"What was the political atmosphere like in Dhaka?" I asked him. "Oh, highly political." Feelings of distance and resentment permeated his initial interactions with the East Pakistani communists. As things progressed, and a coordinating body was formed, political events accelerated the growing nationalist sentiment in the East. After the 1965 war with India, Naqvi remembered the tense mood. Writing about that period in his autobiography, Naqvi reflected: "Most of our subsequent discussions revolved around the possibility of a revolution. A revolution to what end? Were they using revolution as a euphemism for separation?" In 1968, the East Wing decided to form its own party, and the coordination committee fell apart. Naqvi never returned to East Bengal.

Jamal Naqvi went on to be a part of the Central Committee, and then the Politburo of the CPP. Over the next two decades, as one of the party’s main ideologues, he would endure extended periods of arrest and torture (including 16 months of solitary confinement under Zia’s regime). The fascinating stories of those years -- some of which are detailed in his autobiography -- were beyond the scope of my project, and only skimmed over in our conversation. I regret, now, not asking him more. But the past always opens up more pasts, and the more you fill in, the more emptiness you reveal.

In 1991, Jamal Naqvi formally broke with the Communist Party. Doubts which had been fermenting in his mind evolved into full-blown disavowal after a personal visit to Moscow. The glimpse of a real socialist society, and the disappointment and disillusionment that followed, returned Naqvi as a "shattered man," questioning the foundations of the philosophy he had devoted his life’s labor to. This renunciation coloured our entire conversation, every reminiscence of past activism tinged with bitterness. "What is the legacy of the left-wing in Pakistan?" I asked him. "Legacy?" A long pause. "Many of these new communist groups, they are coming to me for advice," he finally said, wearily. "And I don’t know what to say to them. I have nothing to say to them."

What is the value of a history without legacy? When I interviewed Professor Naqvi, the idea of secret Marxist study circles in Hyderabad and red flag protests in Lahore drew on my sentimental hope for finding an alternativity in the past that does not appear in the present. In his book, Naqvi called it the "charm of revolution," which had Pakistani communists thinking it was "out to take over the country like the Bolsheviks overthrowing the Tsars in Russia or Mao pulling the rug under Chiang Kai-shek’s feet." This delusion, he said, was their fatal mistake. But if revolutionary idealism -- which I tried to read as a kind of alternative vision for the early nation -- only ever existed as a delusion, or at best as an unrealised anticipation, then where do we place it on our map of history? These potential futures seem only to decay into nostalgia for a non-existent past.

It was the spirit of "recovery," of uncovering marginalised voices, that led me to the story of the Left in Pakistan. But Professor Naqvi’s story -- especially revisiting it now -- makes me question how to go about that endeavour. Projecting hopes for the past back onto old hopes for the future feels like building roads that travel in circles, on a map that remains fundamentally indifferent.

Yet I cannot discount the theme of possibility, because it does have something to do with the real. Something existed -- if only in the minds of a few men and women -- to shape their thoughts, evoke their emotions, and motivate them to endure imprisonment and torture. This real thing, wherever it exists, sometimes translates into action. Maybe enough action converges at one point to become event, and move history. But when that does not happen, this real thing -- ideology, feeling, anticipation, whatever you call it -- cannot be read on the line between past and future. Then, it only exists where they intersect: where imagination and hope, regret and nostalgia can be produced side by side.

"Have you ever travelled back to India?" I asked Professor Naqvi, at the end of our interview. "Never."

"Would you like to?"

"I feel ashamed of going back to my country, which I left when there was no compulsion to leave."

When I read his obituary, it mentioned that in his last years, Jamal Naqvi’s daughter attempted to acquire a visa for him to visit India. I do not know whether they were successful or not, but it seems to matter that they tried, and that he changed his mind about going back. If one life -- even if only glimpsed through a conversation -- can contain so much: hopes, regrets, insights, illusions -- what all might the life of a nation include?

What I question, when I think of Professor Naqvi and the remarkable life he lived, are the limits of history as narrative, of events as action, of time as linear. "I don’t live in the past and have never been a great fan of nostalgia," he wrote in his autobiography. But some part of us always lives in the past, always lives in the future, always contradicts itself. Is there a way to map those histories -- the histories of emotions and failed idealisms, of renunciation and regret, something that contains the nostalgic memory of the taste of parwar, as well as the very rejection of nostalgia itself? Maybe, at 70, we are finally young enough to try.