Despite all the cultural barriers, old people are happy and healthy at old-age homes, or so they say

Climbing the stairs of an old-age home in Lahore, I see an old man standing in front of the staircase on the first floor, ready to greet me. He seems to be in his late 70s; eyes wide open and a smile on his face. He is lanky and frail but in high spirits upon receiving a guest.

I try to strike a conversation with him, but it appears that he is not mentally stable. He repeats some words and mumbles something that I understand to be, "It is very good and nice here" and, "we have to make it," in English as he keeps smiling. Despite his detachment from whatever is happening around, he is aware that there is someone who has dropped by to say hello.

"He is Nadeem Ali. He was admitted to this old home about six months ago," informs the lady in charge of the home. "Ali’s family -- his wife and son -- are too busy to take care of him anymore. So when he became difficult to deal with due to his mental health, they thought it appropriate to bring him here instead of leaving him at the mercy of servants the whole day," she says.

The serenity and calmness of the place does not give way to dullness or boredom as there is ample sunlight coming in, with proper ventilation. The plant pots placed here and there and a bookshelf with a few books in it give a fair semblance of a home.

Just after having their lunch, prepared according to their health conditions, the old persons have temporarily skipped their routine today of watching tv or taking a short nap, today they have something more exciting to do: chatting with a stranger.

Nestled in a well-kept housing society off Ferozpur Road, this home for the elderly houses eight old people -- four men and four women.

Ali is eager to talk but is interrupted by his roommate, Emanuel. "Sometimes Ali keeps repeating his wife’s name. He misses her dearly even though she and his son visit him on alternative weekends. They also take him home sometimes."

Read also: The 24/7 healers

In his late 60s, Emanuel calls one of his companions from the room to bring him a cigarette, "We’re so happy here. No worries." He takes a pause and continues in a different vein, "As far as our personal problems and grief is concerned, only God can understand what we feel and what we have been through emotionally, especially before coming here and even after."

He doesn’t mind sharing some details, "I am from a village near Kot Radha Kishan. I have an adopted son. He moved away with his wife after he got married. After my wife passed away, I found myself on the road, ending up here."

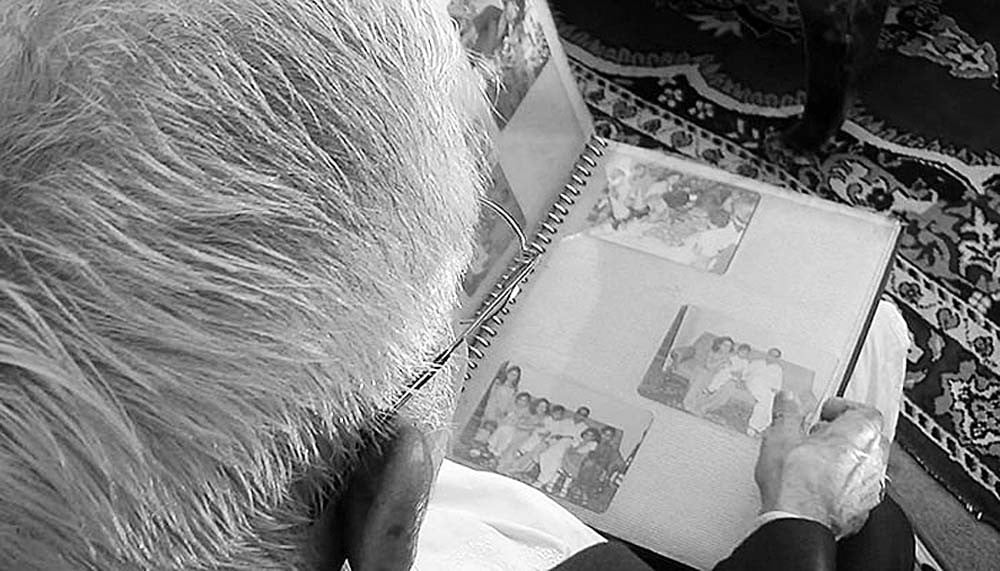

Just like Emanuel, there are others who seem to have embraced their fate and made this home their own. Muhammad Iqbal’s son and daughter are both settled in the US and married with children. Iqbal’s wife passed away in this home a couple of years ago. He has pictures of him and his wife, his children and their children pasted on the wall beside his bed.

"People like me don’t have an option. So I don’t feel lonely because I have all the latest gadgetry to connect me with my children any time I want to," Iqbal says pointing to his computer and iPad. "I couldn’t go to the US with my son because it is costly living there until you acquire citizenship. But living at an old-age home is not all that rosy for everyone. I have been to some other old-age homes briefly where it is not like one’s own home. It’s another world altogether."

According to the website of the Social Welfare Department, Punjab, "the first old-age home in Lahore was established in 1975 under the name of Aafiat. Later, five more old-age homes were established in Multan, Rawalpindi, Narowal, Sahiwal and Toba Tak Singh. These institutions have the capacity to accommodate a total of about 300 old and infirm persons at a time."

Old-age homes in Lahore, or in the rest of Pakistan for that matter, have largely been a neglected subject, with some people not ready to accept the crude realities of a fast-paced life due to our social and cultural norms.

"Since our lifestyle is changing fast, with both the spouses having to work from 9-5, it is very difficult to take practical care of the elderly as the joint family system is breaking down," says Imtiaz Bhatti, owner Darul Zaeef Retirement Home, Gulistan-e-Jauhar, Karachi. "Some people may not like the idea but we need more such homes to help out old people in need. Our job here is to make old people feel better in their last days of life."

According to Bhatti, there are about 10 old age homes in Karachi alone run by various NGOs. Darul Zaeef houses 25-30 old persons, with separate accommodation for ladies and gents.

"Their medical and emotional condition and well-being is our first concern. For example, those who can’t climb stairs are housed on the ground floor. The doctor is on call 24/7 to deal with an emergency and we have regular check-ups and tests for those who are bed-ridden. On the advice of a doctor, staff from a laboratory comes to take samples for different tests," he informs.

Bhatti claims there are no old-age homes run by the government in Karachi. "About three years ago, officials from the Baitulmal department came to me and asked for advice on building an old-age home but as far as I know the plan did not go beyond paperwork," he laments.

Edhi Foundation, he says, probably houses the largest number of old persons in Pakistan, having separate homes for men and women. "There can be 500-700 people or more at a time in one home. Edhi Village at the Super Highway near Karachi has a fairly large number of the old and the destitute," he says.

Names of the residents of the old age home in this story have been changed.