The colonial belief that the teaching of ‘English’ canonical literature is the teaching of humanism has led to certain authors and texts being entrenched in syllabi in Pakistan

One of the underlying assumptions of any university’s operations is that the purpose and process of higher education is a constant engagement and dialogue with the past, present and future. When the university stops engaging with any part of this continuum, we witness the kind of intellectual stagnation prevalent in most higher education institutions in Pakistan, especially those that justify their existence through some warped and often misleading (if not out-rightly falsified) notions of imagined glory in their past. Such institutions -- or rather their administrations -- lack any vision of the future, and therefore cannot engage with making the present more fruitful for their faculty and students, the only two pillars of a university (as opposed to the three-tiered approach where administration is considered the backbone).

These thoughts surfaced in a seminar course titled ‘Introduction to Graduate Studies’ which PhD students at my university in the US take during their entry year. The seminar includes a component on the development of English Studies as a field, and the existential problems it has faced. This line of argument was developed in response to a lengthy discussion on the existence of a ‘canon’ of English Literature.

Having long grappled with the questions of why some very prestigious institutions in Pakistan refuse to radically revise syllabi, and why university education has no impact whatsoever on society, the discussion has prompted me to explore a comparison of English Studies in Pakistan and the US.

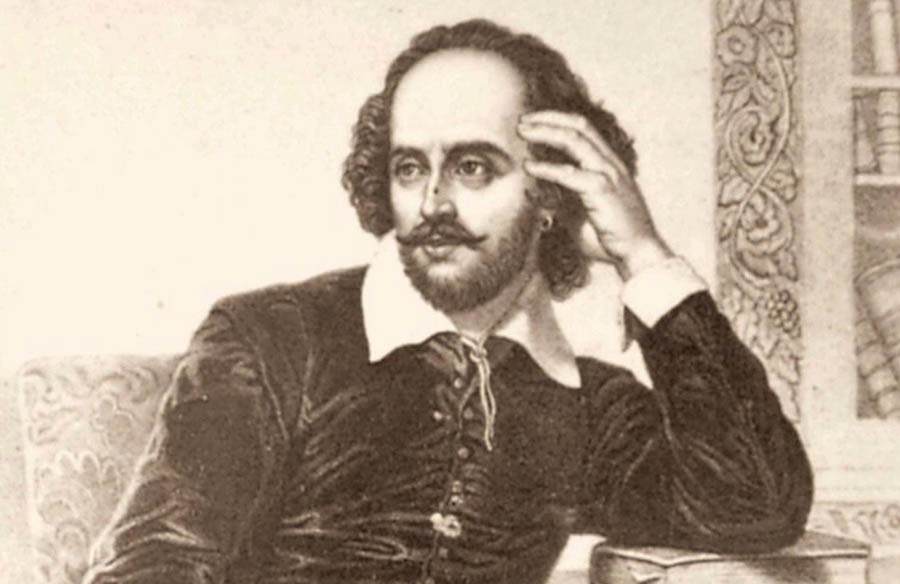

My professor here, a Shakespeare expert who nevertheless has been a part of syllabus revision at two universities that enabled Shakespeare to be an optional course rather than a compulsory one, argues that there has never been a ‘Western canon’ as such since canonical texts have changed over time. This is the essential point where I depart from her stance.

Considering my experience of Pakistani academia, I believe that my American colleagues take the radical post-structuralist and post-modernist de-canonisation and re-canonisation of literature for granted. My colleagues are working towards PhDs in Chicana literatures, Disability Studies, and ecocriticism. All these specialisations, made possible by their American undergraduate thesis experience, assume the possibility of question, debate, and re-engagement with literature in a way that few places in Pakistan have been able to envision.

For example, can we even start to think about removing Shakespeare from our syllabi? That is a question that would startle, shock, and offend most English departments in Pakistan. An institution as prestigious as Yale has recently made Shakespeare optional. Despite the centuries of debate around the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays (based on factual evidence that very few plays were written by single authors at the time, which implies that Shakespeare must have collaborated, most probably with Ben Jonson), English departments in Pakistan would find it sacrilegious to even consider the possibility.

Read also: The lingering canon

The word ‘canon’ has roots in Christian theology. It is a decree of the Church, and therefore, crucially, it cannot be challenged. A canon is essentially Scriptural, but in the evolution of a literary canon in the West, it became Personal. From the canonisation of scripture, literary studies turned towards a cult of personality. Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Keats, Dickens, Austen, and many others were given almost prophetic stature by critics and teachers of literature.

Most interestingly, at some point in post-partition subcontinent, Byron and Shelley (the two most canonised and iconic British Romantics) were de-canonised. One possible reason could be the state’s fear of subversion (a theme particularly articulated in Byron).

The argument advanced by those who believe in the absence of a canon is that the choice of certain authors as canonical is based entirely on the subjective historical forces that have shaped the intellectual history of Europe. True as this is, it does not preclude the formation of a canon. European intellectuals, particularly after the colonisation of India, had to present the West as the civilised Other in order to justify the barbaric suppression of native rights.

Also read: The canon question

Ironically, this ‘civilisation’ could not be proved simply through the scientific superiority of the West. Therefore, Western imperialists had to conjure up images of a ‘civilised’, ‘advanced’ and ‘humanising’ literature which would miraculously transform the perceived savageness of the native colonised into humanity. This was the birth of the erroneous belief that the teaching of literature makes humans better, and must therefore be made compulsory at all levels. Thus, a canon -- however false, unrepresentative, and cruel -- was born in the colonies, and eventually travelled to Western universities.

The irony of this canon is two-fold. For one, though propagated mainly by British imperialists, it sought its origins in Greek and Latin literatures and philosophy. This was, in fact, a clever attempt by the British Empire to present colonisation as not just a British project, but more of a European vocation.

Civilising the uncivilised was the duty of all Europeans. The British appropriated the Greek, Latin, German and French intellectual traditions (both literary and philosophical) to posit the entirely falsified notion that the lingua franca of European thought was English! To this, the newly minted canon of Beowulf, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Samuel Johnson, and the Romantics, provided the necessary textual grounding.

Also read: English Literature and ‘the elegance of deceit’

The second irony is that while Western academia (led by French and German philosophers and literary critics) successfully moved beyond this constraining canon in the 20th Century, the once-colonised held it to their hearts and souls with the same set of convictions that had originally been visualised by the colonisers.

In the post-colonial state of Pakistan, for example, not only did Shakespeare and Wordsworth become objects of emulation for young writers; rather, they became far more entrenched in the syllabi from school to university levels. This was made possible by the lingering colonial belief that the teaching of ‘English’ canonical literature is the teaching of humanism, that most desired of qualities in a ‘democratic’ state.

All said and done, the belief that a canon does not exist can be misleading. The evidence of the status accorded to several texts and authors in most Pakistani institutions is testimony to the lingering persistence of a canon.

This essay is the first of a two-part series