What if provincial governments went about collecting quantitative and qualitative data about divorce? Would that impact legal and social policy?

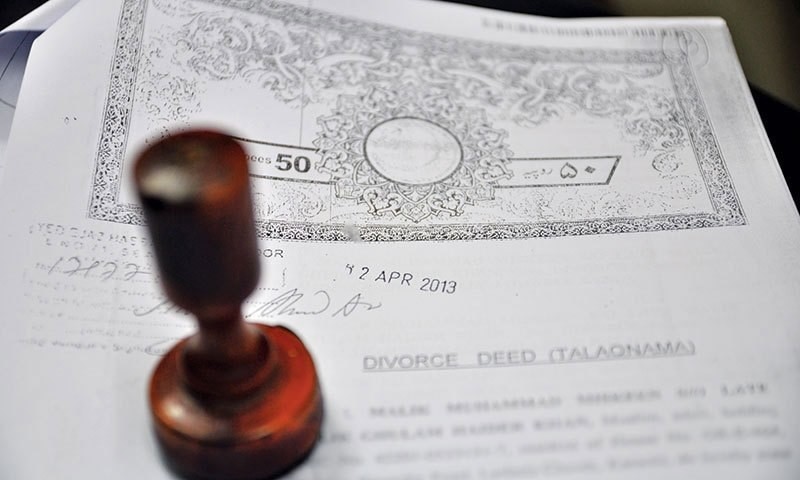

Four out of five Pakistanis believe that the divorce rate in the country is increasing, the Gilani Research Foundation Survey revealed earlier this month. Given that Pakistan has never calculated the rate of divorce, neither on the federal nor provincial level, we have unfortunately resorted to opinion polls about divorce rates i.e. anecdotal or observational data that is being quantified.

But what if this wasn’t the case? What if provincial governments, under which family matters such as divorce fall, went about collecting quantitative and qualitative data about divorce? Would that impact legal and social policy?

The Punjab Commission on the Status of Women believes it would. Fauzia Viqar, the chairperson of the Commission, has broken the stagnation surrounding divorce data collection. Last year they launched an interactive website that collected data from across 1,026 Union Councils in Punjab, and presented it district and city wise. We can now see how many people filed for divorce in 2015 across the province.

According to Viqar, this data has already impacted policy. "We can see on the website that 24.4 per cent of the divorces are initiated by women. This led us to question if women have easy access to family courts? Are they treated in a sensitive manner when they approach these courts and services?"

These questions led to the training of 39,000 nikkah registrars and 10,000 government officials. "It is now the duty of a nikkah registrar to ensure that the nikkahnama is filled in such a way that women filing for khula do not feel trapped. For example, it’s not enough for the man to write the dower amount in the contract, it also has to be identified with supporting documents that should be attached with the marriage contract."

Viqar says, "Traditionally we are not a data-driven country," but things are changing. "At least in the Punjab, the government is starting to focus on evidence-based policy."

Next year, when the data for divorces in 2016 is collated with this 2015 baseline data, for the first time since the inception of Pakistan, we will know the divorce rate of Punjab.

But what about the remaining provinces?

Maliha Zia, lawyer, researcher and activist, is not too worried about other provinces falling behind. The Sindh Commission for the Status of Women just recently had their chairperson appointed and once their mechanisms are in place, it will be easy to replicate Punjab’s example and collate divorce data, and other provinces can follow suit, says Maliha Zia.

But the researcher does have other concerns. Maliha Zia says that it is qualitative data on divorces that will show emerging trends and patterns; quantitative data on its own is not enough.

While she is curious for the Punjab Commission data to churn out its first rate next year, she says: "We also need to answer why the rate is increasing. I can see more women asking for divorces and taking stands, and quantitative data will solidify our anecdotal observations, but what are the reasons behind this? How much of a part is domestic violence playing? What are the ages of women asking for divorces? Who ends up with the children? What are maintenance trends? How many of these divorces are khulas and how many are talaaqs?"

She reminds us that collecting qualitative data is no walk in the park. In the final divorce certificates that are submitted in Union Councils, lawyers will often copy-paste the petitions. "We write things like ‘The husband and wife cannot live happily together within the limits prescribed by Almighty Allah,’ which is fine but we need to be more explicit in the petitions about why the divorce took place, since that will help in collecting qualitative data," says Maliha Zia.

However, she says, there is no doubt that data can bring about impact. "The most recent law passed on rape was pushed forward because the low rate of conviction of rapists was often quoted while discussing the law."

Looking at recently passed laws, such as the rape law mentioned above, and understanding their impetus is a good way to prove that data collection can bring about policy change. Afiya Zia, a feminist researcher and activist, cites the recent laws that have been created for the protection of the transgender community. "Only when they were being identified and recognised by the state, and when NADRA began registering them, did we start making laws in their favour. And only then were there attempts to count them in the census, to quantify them," she says. "The same way marital behaviour and practices surrounding marriage need to be quantified, that’s the first step to creating policy for divorcees".

Afiya Zia takes us back to 1961 and the creation of the Muslim Family Law, which at the time was progressive. "But all laws must be reassessed and updated, and our family laws are no longer progressive," she says. And the impetus for the revamping of these laws should come from data collection.

She adds that data will help to improve laws surrounding dowry, dower and child custody. "Only when we know how many women are given the short end of the stick in these battles, can we work towards building better systems around these laws."

However, there are many women, men, and families who would be loath to admit that they are divorced, because of social taboos. For such people, and those who do not have easy access to Union Councils, Afiya Zia suggests, the state should provide incentives. Taking the example of Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP), which encouraged women to identify themselves in order to be beneficiaries, the state can set up a rights-based system for divorced women, says Zia. "They could link identification with the right to benefits, such as custody."

If there is no motivation for a divorced woman, provided by the state, then why should she identify? You need incentives to fight the stigma against divorced women, only then can you count them.

It works both ways, the more women come forward and identify, the more benefits they could demand; and the more benefits they receive, the keener more women will be to identify.

But what concrete benefits could the state provide to the divorced women? Data can help reveal this, if we first ask them what it is that they need.

Sonia Qadir, a lawyer and researcher who has previously worked with the Punjab Commission, says "Ideally speaking, data can help propel policy in favour of women. For example, if we see that the number of divorced women is growing, the government may feel compelled to build more women’s shelters".

She explains that the existing shelters for divorced or single women only host women who feel very vulnerable to violence hence the security in these buildings is high. Single or divorced women cannot hold regular jobs while living in these "almost prison-like atmospheres".

One can, ideally, hope that data collection will show that vulnerable and/or divorced women need subsidised housing, subsidies to study further, day cares for their children, and work opportunities, among other things.

Additionally, impetus is also needed for a post-divorce maintenance policy that must be drafted and implemented as part of regular court procedure, given the difficulty single women face raising children while working for a living.

However, information is power that can be manipulated to serve purposes that may not work in favour of women. It is no secret that the concept of ‘rising divorce rates’ make our society feel threatened. Take, for example, the mood when The Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2009 was placed before the Senate. Before the Senate could sign it, the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) publicly criticised the bill on the grounds that "it would fan unending family feuds and push up divorce rates".

The bill was delayed for months out of the fear of rising divorce rates. If it was proven that divorce rates were, in fact, rising, the CII would have a field day saying "we told you so". Of course there are also multiple unsubstantiated studies that "prove" (without actual data) that the media and western culture is causing an increase in divorce rates.

Sabahat Rizwi, lawyer and advocate, on the one hand believes that data is crucial to bring about legal change, but she is also apprehensive of the media or the CII portraying a high rate of divorce negatively.

"They will say the high rate of divorce is due to lax approach of courts, or too many independent women, or western influence, or something thoughtless like that and all the hard work of activists will go down the drain," fears Rizwi.