The Karachi Biennale has been credited with reviving spaces in the old town, but is it an equitable and thoughtful revival?

For seventeen years the 19th century bungalow at 63 Commissariat Lines was closed, unused. The historical building which opened to the public for the first time last weekend was done on the behest of the Karachi Biennale 2017.

The bungalow is one of twelve sites chosen by the Biennale team, six of which are concentrated in Saddar, the old part of the city. "Galleries get a certain kind of audience," says Zarmeene Shah, Curator at Large for the Biennale. "Conversations are then limited to a certain audience." Keeping this in mind, the curatorial team’s aim was to bring the Biennale to the city and to spread discourse outside Clifton and Defence.

For this, installing art in historical spaces and restored buildings has proven to be crucial. All of this, Shah clarifies, has been possible through the generosity of people who have lent their spaces without any feels -- the Biennale has been executed on a shoe-string budget.

There is NJV Government Higher Secondary School -- a large colonial structure standing at one of the quieter intersections in the heart of Saddar. Here the curatorial team has experimented with whatever space they had available -- the lobbies, the classrooms, even the corridors.

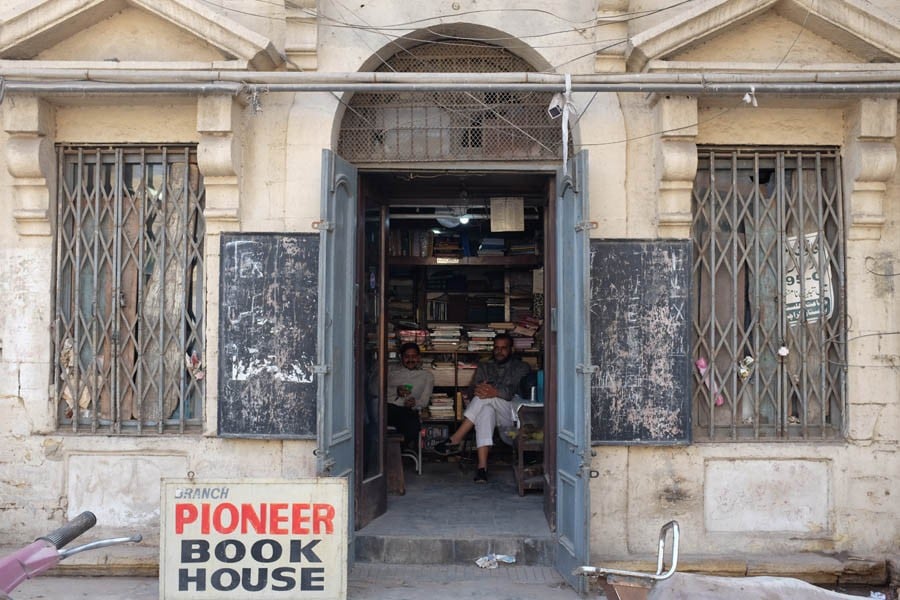

Then there’s Pioneer Book House, the oldest bookshop in Karachi dating back to 1945; Claremont House, another restored 19th Century colonial structure once used by railway officers; Capri Cinema, one of the oldest single-screen cinemas in Pakistan; Jamshed Memorial Hall, once home to Karachi’s Theosophical Society; and Frere Hall, a popular museum and heritage site that needs no introduction for any

The question is: by activating these spaces for exhibits, to what extent is the Biennale contributing to the revival of old parts of the city?

A bright blue banner outside 63 Commissariat Lines identifies it as one of the Biennale locations, but the gate is closed. A guard answers our knock, pushes the gate open when we tell him why we are there. Inside, we’re greeted by the impressive two-storied building, its latticed windows glinting with a fresh coat of blue paint. It’s 12:30pm and people haven’t yet started filling in.

Inside, we are asked to register our names and NIC numbers. A Biennale volunteer guides us around the gallery, helping interpret the art, pointing out the installations spilling along the front yard.

One of the guys who looks after the place tells us the site was restored in thirty-five days. This is the first event he’s known to happen here. "On Sunday, 300, no 400 people showed up," he says. "Not from the area though." Still, in a sense -- the space has been revived. Since the Biennale opening, people have not stopped coming in.

Later, when we’re art hopping at the NJV school, an artist friend asks what we even mean by revival. "Revival for whom?" she asks. "What does it mean to revive something that is already in use by the locals?" She feels that when the Clifton and Defence populace talks of revival, what they really mean is dragging themselves to the other part of town.

Zahid Mayo, one of the artists whose works have been featured at the Commissariat bungalow-- a running series of calligraphy on trees -- points this out as well. "The audience consuming art in our society is an exclusive audience," he says. While he was working, he noticed there were wood workers and craftsmen outside the bungalow, but none of them were called. "Ordinary people do not know about it [the Biennale]".

A site that has come under particular critique is the Pioneer Book House. The bookshop was restored earlier in the year by writer Maniza Naqvi; the chosen installation for this site, titled ‘Broken Streetlight’ is a ruined telephone pole that runs through the open ceiling, up to the second and third floors of the bookshop. Consumers and artists alike on social media have pointed out that this installation is in bad taste, and is an example of the Biennale team’s disregard for class politics.

Read also: Reclaiming life

But Zarmeene Shah explains how the curatorial team took several months to plot out the artwork at every site. "At every stage, we were very conscious of what the works mean and how they interact with the space," she says.

What one cannot argue -- regardless of what they think of specific art pieces, or of the exclusion of local craftspeople from the process -- is that the Biennale has sparked conversations about art, aesthetics, and politics as well. As Mayo says despite his reservations, "At least something is happening." He feels events like the Biennale are a step in the right direction.

Marvi Mazhar, architect and heritage consultant, points out how the Biennale is allowing people to go into spaces that were previously closed to them. "Who goes there usually?" she asks. "Everyone’s seen these buildings from the outside. Only when you go inside, do you see how excellent these spaces are." For her, the question is of engagement -- what did the students at NJV School think when the installations were being placed? How do ordinary citizens feel when they see these sites of heritage? "The Biennale has proven that when you open your spaces to the public, a conversation is sparked on history."

Mazhar has spearheaded the restoration for several of these sites, particularly 63 Commissariat Lines and the Claremont House. She feels it is about time that citizens begin engaging with heritage sites, taking a stand when they’re torn down. It should not be the job of architects and urban planners alone to keep rescuing these spaces.

"Witness isn’t simply about the work inside," she says. "It is also about paying witness to your heritage. If you’re going outside your comfort level to go to these places, something has been done right."