Nasir Abbas Nayyar’s emotional struggle as he tries to negotiate with a new city makes for a gripping read

His safar (journey) begins miles in the air, on a plane to Frankfurt. Gazing at the vast greenery spread across a blue expanse from his airplane window, he concedes that the safar that South Asian cultural idiom considers to be waseela-i-zafar (or one that paves the way to success), is the kind undertaken strenuously on foot or horseback, the rail (which has a romance of its own in the region) or one that involves traversing through rough waters.

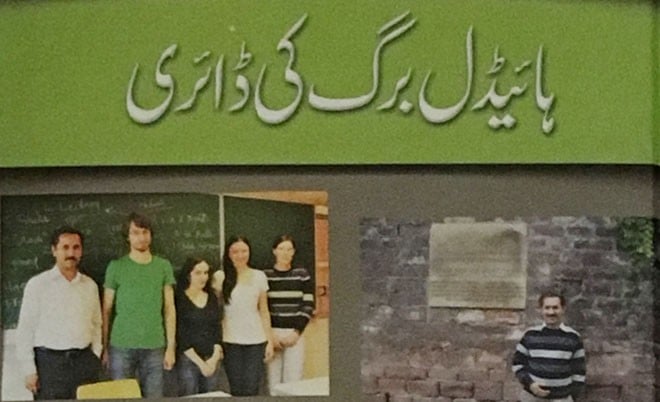

Urdu literature critic and writer, Dr Nasir Abbas Nayyar takes readers to the city of Heidelberg where he went to study at Heidelberg University as a post-doctoral fellow researching Urdu texts during the colonial era (Nau-abadiyati Ehed kay Urdu Nisaabaat) in 2011 in his book, Heidelberg ki Diary.

The conversation opens with reflections on the rationale for writing a diary. For Nayyar, maintaining a diary is inherently rebellious. It is a response to the lopsidedness of memory. If frozen in time on a journal, to revisit with a renewed perspective time and again, chronicled moments can escape the tyranny of memory -- which not just blots out happy incidents but dwells more on unpleasant events. This journal, whether it belongs to an ordinary person or an acclaimed writer is where the tangible world collides with the world of ideas and thought.

True to this notion, he brings out the significance of mundane routine life, in terms of the lived human experience. Elegant in its simplicity, the language makes ideas accessible. The author’s emotional struggle as he tries to negotiate with a new shehr makes for a gripping read. There are times when his solitude is a hymn to life and times when it stings: The diary entries grow shorter. More further apart. The tone darkens. But then, he returns with an evolved sensibility.

From travel jitters upon landing in Frankfurt in a post-9/11 world to over-packing clothes for a ‘colder climate’ and going through a random bag check on the airport, the author manages to comment on the political and sociological realities but keeps the readers engaged in a subtle manner. While appreciating the polite and friendly demeanour of ordinary Germans who helped him with directions as a student, Nayyar muses over the fact that he hadn’t counted the airport security official who checked his bag at the airport as German. "Because the police is just the police -- no matter what country it is, they are all the same!"

His commentary begins to turn the popularly-held beliefs in Pakistan, regarding culture in the West, on their head as he probes the binary of ‘eastern’ and ‘western’ values. Sexual freedoms and the relationship between parents and children emerge time and again in his writing. He aims to view the debate from a ‘scholarly’ distance, and tries to maintain a semblance of neutrality as he articulates his position in both debates.

What he does denounce blatantly, however, is the link drawn between the cultural heritage of a particular region and the respect for human relationships -- which is heartening. He substantiates this claim by shedding light on the historical prevalence of patricide in the East -- Babruvahana killing Arjuna in Mahabharta and Mughal emperor Aurangzeb killing his brothers and banishing his father to the Agra Fort and leaving him there to die. An interesting thought he muses over here is that the existence of such a violent dynamic was completely unheard of between mothers and daughters.

The entries create picturesque images of Neckar, and as this happens, the pace of narration slows down allowing the reader to tap into Nayyar’s imagination -- Iqbal and Attiya Faizi boating across the river, families picnicking here, and people cycling and jogging along the river.

He attends conferences beginning without words of praise for the Almighty, he goes to offices where class and power relations as manifested in South Asia are absent (bosses brew their own coffee; they do their own chores), people are always busy working, and keen on exchanging ideas. The novelty of a new experience -- that of being in Germany -- dissipates over time and he delves into legitimate concerns as a Pakistani post-doctoral candidate at the Institute of South Asian Languages. Nayyar feels the extent of the difference between the West’s perception of Iqbal and that of Tagore.

There is a grand, imposing statue of Tagore at the building while Iqbal only has a street named after him. "Had Iqbal not done his PhD at University of Heidelberg and not written a poem about River Ufer, would he be known to this part of the world at all?" he asks.

He criticises the lack of interest on part of successive governments in Pakistan with respect to furthering the cause of Urdu and Pakistan’s cultural heritage, comparing it with how it’s done "at such an old and esteemed university [Hiedelberg University]".

His entries flow naturally into related debates: the Urdu-Hindi divide as languages of Pakistan and India respectively, ideology as a construct despite its seemingly real experience, and the role of English as the language of research but not suited for writing South Asian fiction in, and eventually the idea that translations of Urdu literature should serve as a tool for Western audiences trying to understand Pakistan.

All the while, like most nationals living away from Pakistan, he compulsively maps the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them’. At times it is the little things -- their mannerism and gestures. Invitation to have cups of coffee together heralds the beginning of friendship here. People smile at each other. At other times, it is the bigger questions: how do they see themselves as a society? He quotes snippets from conversations in Germany and reflects on these: In Pakistan, trees are cut to expand roads and this is seen as an inevitable and practical way to go about the issue, whilst in Germany the idea sounds profane. A cinema and a church face each other in this country while in Pakistan today, such an occurrence would seem to be out of question.

But then Nayyar recalls references to wine and the mosque would be made in the same couplet by Urdu poets:

Tuj ko masjid hai mujh ko maykhana

Vaiz apni apni kismet hay

Nor is it possible to think of the Shahi Masjid (Badshahi Mosque) without the Shahi Mohallah (red-light district nearby), he remembers. Yet, the diary does not spiral into a long drawn-out soliloquy.

Though the preface clearly tells readers that the diary was never conceived as work meant to be published, the author successfully touches upon a variety of ideas in a 152-page-long attempt at preserving the ‘now’ as it is.