While the idea of Pakistan has been broad, first encompassing all the Muslim of India and later the entire Islamic world, the territory of Pakistan has been the victim of gravity

Writing in his important work on Pakistan as ‘Muslim Zion’, Faisal Devji has argued that since Pakistan was an ‘idea’ its territorial imagination was very fluid. Hence, Jinnah could stake a claim to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, despite the fact that they were not Muslim majority, argues Devji. So like the Jewish ‘Zion’ which might have actually materialised in Argentina, territory was a secondary consideration to the idea.

Possibly in a testament to its imagination, Pakistan was born on August 15, 1957 without any boundaries. The Radcliffe line which split the Punjab and the Bengal, though decided, was only declared on August 17, 1947. Hence for two days people near the border were unsure which country they were a part of, and the leaders of the countries did not know the extent to which their power lay.

Where the border between the two Punjabs and Bengals was still under wraps, Pakistan did indeed acquire an extra territory -- the State of Junagadh, three hundred miles away from Karachi on the Kathiawar coast, acceded to Pakistan. Junagadh, the most important state in region, had a Muslim ruler but an 81 per cent Hindu population. Its area was also not contiguous with several of the state’s pockets in other states, and other states having enclaves in Junagadh. Economically too, Junagadh was inextricably tied to the states around it, all of which had acceded to India. But then Pakistan was an idea, and therefore it did not matter where the territory actually lay.

Already, Pakistan was a peculiar country: it was a country divided in two wings. While for empires this was not an issue, after all, Jinnah had declared that if England could rule over India from thousands of miles away, why could Pakistan not be ruled when there was only about one thousand miles between the two wings.

However, there was a critical difference here. In empires, the metropole ‘controlled’ and ‘ruled’ the colonies, and the colonised had limited rights, hence it was one-way rule and control. In a disagreement or conflict, the metrople was always right. But Pakistan was going to be a modern nation state with no difference of power between its different units. Since the capital, and hence central power, was to be in one wing, what would happen if the other wing cried neglect? How would differences be dealt with between the two wings?

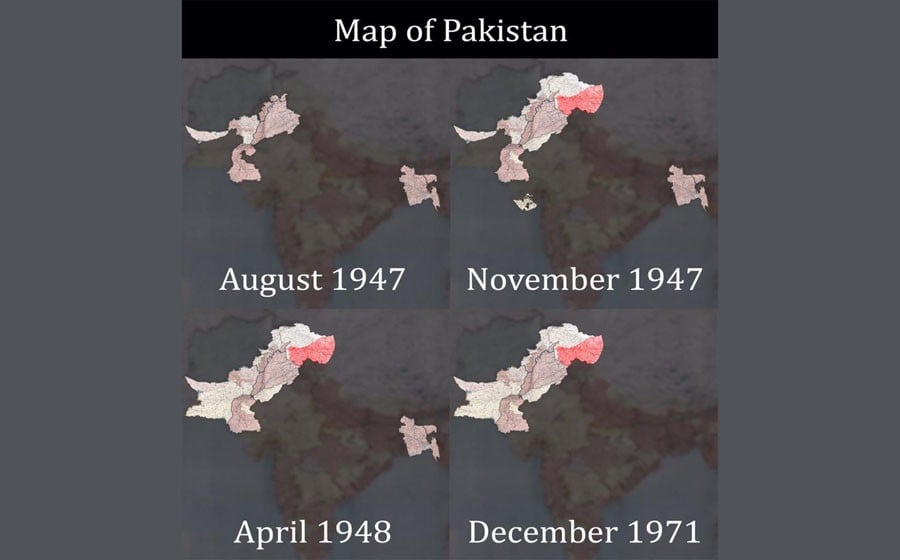

In the last seventy years just as the idea of Pakistan has largely been under threat, the territory of Pakistan has also changed several times. As the attached map shows, Pakistan is perhaps one of the only modern countries whose boundaries have changed so much since inception. The ‘moth eaten’ Pakistan achieved in August 1947, filled up between August 1947 and April 1948, with the accession of eight princely states, but then just as the territory was increasing, it also decreased with the occupation of Junagadh by India in November 1947.

But then Pakistan again gained territory when Gilgit Agency revolted in November 1947 and the two states of Hunza and Nagar joined the country. The war over Kashmir too added a bit of territory in 1948, which Pakistan called ‘Azad Jammu and Kashmir.’

For the next twenty or so years, the territory of Pakistan remained largely constant, excepting a slice of land it itself gave to China in 1963, in the otherwise disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. But then Pakistan, the idea and the territory, again made world headlines in 1971 when, for the first time in modern history, a majority seceded from a minority. The bloody civil war of 1971 ended with the emergence of Bangladesh. The other ‘wing’ somehow felt that that distant Karachi was much worse than the even more distant London, and so rose in revolt.

Pakistan the idea and Pakistan the territory have perhaps always remained in a tension. While the idea of Pakistan has been broad, first encompassing all the Muslim of India and later the entire Islamic world, the territory of Pakistan has been the victim of gravity. Despite Pakistan’s claim on the Muslims of India, they remained in another country, in fact, territorial Pakistan did not want them, but still the idea of Pakistan did not end its claim. Similarly, while the idea of Pakistan wanted to become the lynchpin of the Muslim world, the territory of Pakistan was very wary of the Muslim countries of Afghanistan and Iran and their designs on its territory.

Now it is in 70th year, perhaps it is time that the idea of Pakistan and the territory of Pakistan become friends. Maybe they should recognise that both need each other to survive, to flourish and quite simply to remain. Both the idea and territory have given grief to each other several times in the past, so perchance now they can work together towards a common goal, identity and existence. Perhaps now both the idea and territory should be only Pakistan.