Afghanistan will remain unstable until the US comes clean about its real intentions in the region

| C |

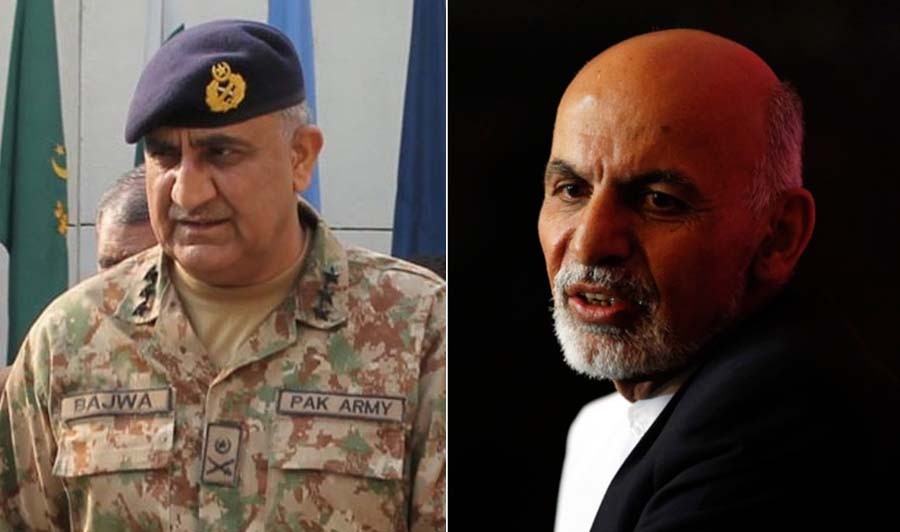

hief of the Army Staff Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa’s visit to Kabul has revived some hope of change in Pak-Afghan relations. A number of developments in the recent past suggest that Pakistan is under tremendous pressure to mend its ways in Afghanistan. From the US to India to Afghan national government and recently China, all are arrayed against Pakistan in the wake of Donald Trump’s recently veiled strategy for Afghanistan and South Asia.

To which direction will Pakistan foreign policy on Afghanistan move? Will the past be Pakistan’s future or the country’s foreign policy will usher in a new arena?

Pakistan is frequently criticised for running with hare and hunting with the hound regarding its fight against Taliban and its alleged support to elements of the militant movement in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, what we fail to recognise is that the US Afghan policy is riddled with contradictions. Put differently, the biggest source of instability at the court of Kabul is the US policy towards Afghanistan.

We have seen that since 2001 the US has been playing both ends against the middle. As a result of turning a blind eye to regional state interference in Afghanistan, the US has implicitly given leeway to regional actors to pursue their narrow interests in Afghanistan only to strengthen the hands of Taliban who now control no less than 40 per cent of Afghan territory. Despite much debate it generated, Trump’s strategy falls short of what is essential for stabilising Afghanistan.

The strategy has singled out Pakistan as the sole culprit of instability in Afghanistan. It has failed to recognise that, besides US dual policy, it is regional states -- and not only Pakistan’s -- interference that stands responsible for triggering instability in the country. Sadly, nothing has changed in the American policy even after the recent unveiling of Trump’s strategy for Afghanistan and South Asia which laid down Trump administration policy to defeat Taliban.

Pressurising Islamabad to not support Taliban is an old riddle which keeps on revisiting. Pakistan has traditionally honed its skill of adapting to the US pressure without compromising on its means to realise the so-called national interests. Policy makers here appear to have realised American Achilles’ heel: that the US wants a ‘managed instability’ in Afghanistan. Same hold true for other regional states! Seen this way, apparent contradiction in Pakistan’s Afghan policy is the result of contradiction in America’s Afghan policy. China is a different story altogether, however.

In recent years, Beijing’s policy in the Pak-Afghan region is mainly driven by its economic considerations. Whether BRICS’ declaration was a Chinese sop to India post Doklam border military standoff or China meant it might be a moot point, what is clear is that Beijing has demonstrated unrivalled skill to separate economics from politics in its dealing with other states. This policy is not without implication for Pakistan.

There is a widespread perception that China is reluctant to give unqualified support any further to Pakistan’s alleged support to Islamist militants, including Indian held-Kashmir based militants and Taliban. As a result thereof, the mainstreaming of banned Jamaat-ud-Dawa (JuD), as it launched Milli Muslim League in August, is the harbinger of change in tactics than militant ideology on the part of the militant outfit. The whole exercise appears to give a friendly façade to the militant entity so as to relieve international pressure without relying much on China. On the count of Taliban, China appears to be sitting on the fence, however.

One factor determines as to what extent China may nudge Pakistan to follow a particular stance. In all probability, China, in order to execute its One Belt One Road project and build on its economic initiatives in Afghanistan, may throw its weight behind any group which has the capacity to impose order in the country. It does not matter much who, either Taliban or any democratic regime, rules Afghanistan though the latter is preferable because of the former’s previous association with Uighur militants back in late 1990s.

Under existing circumstances, Taliban, though they control large swathes of territory in Afghanistan, are not worth much preference for China. Neither is the Afghan national government which, for the last 16 years, has remained unable to stabilise the country. Thus, China, in all likelihood, may not force Pakistan to end its alleged support to Taliban. What are the odds of change in Pakistan’s Afghan policy?

There are two states, the US and China, that can help change Pakistan policy towards Afghanistan. A stable Afghanistan lies in the total cessation of all outside interference in the country. This calls for an end to US dual policy: either Taliban are an enemy or a friend. China, on the other hand, has neither any better option nor does status quo suits its interests. Whereas stable Afghanistan is in the interest of China, instability in the country has only helped prolong the US stay at the court of Kabul.

Afghanistan will remain unstable until the US comes clean about its real intentions! In the given context, past is the future of Pakistan’s Afghan policy.