Until a solid solution to preserve our existing natural resources is sought, the development plan of Lahore shall remain a vague ideal

The city of Lahore, reeling under the vagaries of a sprawling urban centre, looked stressed as the sun took a dip in to darkness, unnoticed and unappreciated, behind the huge LED advertising board running an ad campaign for a shopping festival at a newly opened shopping mall.

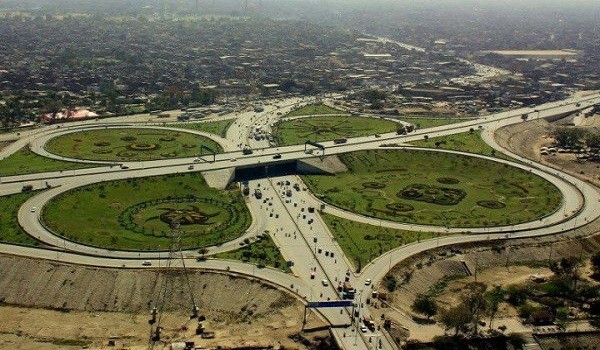

The countdown timers at the traffic signal installed to ease the flow of traffic were switched off as a traffic warden desperately tried to manage vehicles stuck in a gridlock, but to no avail. The city with all its signal free corridors, flyovers and underpasses, was still choked.

Once known to be a well-tempered metropolis rooted in altruism, aligning residents with nature, connecting every tree to a person, every building to a neighbourhood, and every person to the city, it seems that Lahore has now lost the metagenome that held together the elements which bound the various systems of the city in harmony. In our crazed quest for a ‘world class’ city, the follies committed and endured in the name of progress have led us to a state where Lahore has lost its meaning, fairness and sense of purpose.

The ongoing development in the city can be termed as ‘unfit fitness.’ With the concentration of fine particles suspended in the air rising to over 100 µg/m3, which is four times higher than the standard safe PM 2.5 level at 25 µg/m3, depleting acoustic quality and traffic congestions are warning signals of a more deep-seated crises for the future.

Despite the progress -- or what is known of it in this part of the world -- we’ve witnessed over the past couple of years is not sufficiently adaptive to deal with the urban and environmental staring at our faces.

Whereas the city should have been a key nexus of the relationship between its residents and nature, the city planners have pushed away the larger ecology factor out of the equation. The transformation that was meant to grow from within the city was unfortunately brought into the city without paying any heed to how the metropolis would respond to these changes. The promised benefits that were to be derived from urban natural resources did not happen, and as predicted, they could never have happened in the first place.

To receive the full value and reap the economic benefits from the natural resource balance, one needs to work with nature and understand the interdependence of all living things.

Unfortunately for us the preservation of environment is often perceived as a battle between development and nature. Therefore, the current concept of sustainability, though a laudable holistic vision, is subjected to the same kind of criticism of vague idealism made against the comprehensive planning of the city in the late 1970s and 80s. In fact, the idea will be particularly effective if, instead of merely evoking a misty-eyed vision of a peaceful ‘ecotopia,’ it acts as a lightning rod to focus on conflicting economic, environmental, and social interests. The more it stirs conflict and sharpens the debate, the more effective the idea of sustainability will be in the long run.

But to truly walk out of our current impasse, the city planners need to integrate the collective worldview of ensuring that the city is inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable for all inhabitants, including the urban wildlife and flora. Growth can occur -- and should -- but it needs to be planned in a way that promotes sustainable and smart interventions, addresses appropriate densities and integrates mixed use to keep the size compact.

Smarter development is the answer to our urbanisation woes and policy makers should not pussyfoot around this issue, but rather take it head on. Until we opt for a solid solution to preserve our existing natural resources, the development plan of Lahore will remain a political pie in the sky.