The government’s inability to take decisions on Fata and implement them reflects an alarming level of chaos at the highest level of decision-making

With the formation of Fata reforms committee in November 2015, the genie of change in Fata was let loose. The State is unable to deal with the genie it has itself set free. There appears a lack of political will, commitment or understanding on the issue.

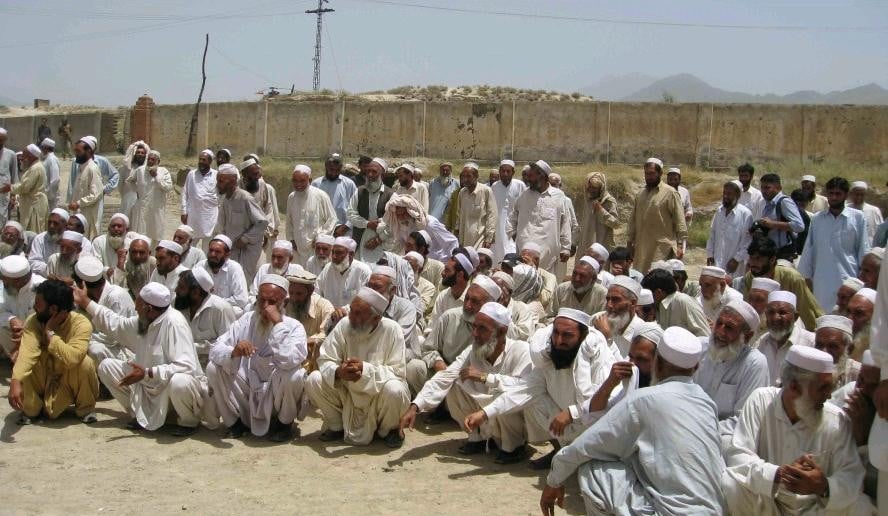

A repeated process of consultations, decisions and silence, furthers the confusion and adds to an alarming level of alienation.

After a long process of consultations, the Fata Reforms Committee came up with a comprehensive plan for mainstreaming Fata, through merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with a timeline in mid 2016. When it was presented before the PM finally, he ordered another round of consultations. The hype and hopes generated by the report, despite reservations, mainly on the Rewaj Act, were dampened but not diminished.

The report, with minor changes, most important being changing the Rewaj Act into Rewaj Regulations, was finally presented and approved by the Federal Cabinet. Only Rewaj Regulations were presented in the National Assembly just before the Budget this year.

Presenting Rewaj Act, which was considered a bad copy of FCR, made a mockery of the whole plan for mainstreaming Fata. Rewaj Regulations could have become acceptable as a bad part of a whole package, which contained a phased merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and extension of Peshawar High Court and Supreme Court jurisdiction.

However, even the controversial Rewaj Regulations were neither discussed nor approved and implemented. Latest in the series of confused decisions and not even implementing them is the decision by the Federal Cabinet to extend jurisdiction of higher judiciary to Fata. But there is a catch in it; rather than the Peshawar High Court, the government has decided to extend Islamabad High Court jurisdiction.

The government’s inability to take decisions on Fata and implement them reflects an alarming level of chaos at the highest level of decision-making. Different analysts explain this inability as conscious, well-thought out strategy (even if they disagree with it). Many try to explain this with reference to Pakistan’s Afghan Policy, claiming that Pakistan needs an invisible space adjacent to the Afghan border. However, even if Pakistan’s decision-makers approach to Fata is affected by their Afghan Policy, it is misplaced as Pakistan’s Kashmir policy does not require any Fata there.

Read also: Women power

Similarly, the apprehensions of those among Pakhtun nationalists who oppose mainstreaming Fata with reference to the Durand Line are mistaken about the relationship between the two. Fata status will not affect the legality or otherwise of the Durand Line either way. The grazing rights of those living on both sides of the Durand Line will not be affected by Fata status.

Cross-border movement or policy of Afghanistan to give special treatment to the people of Fata has nothing to do with the status of Fata and is an issue of Human Rights of communities divided by state boundaries everywhere, along with administrative and political questions.

Simply, the status of Fata is not due to the Durand Line Agreement; it is due to the Constitution of Pakistan. The issue is being confused by different people, perceptions and viewpoints.

The issue of Fata is basically the issue of democracy and human rights in the State of Pakistan, irrespective of the status of any territory that is in its sovereign jurisdiction. This is simply a reflection of reluctance of the State of Pakistan to take decisions on fundamental issues that can be seen in other areas too, arising more out of its inability, both intellectual and political limitations and continued crisis of State and society.

Fata appears to be an area of least priority to the major political parties of this country. Even though the issue of Fata mainstreaming matured and came closest to fruition during PML-N’s current government, it has never shown any real commitment to it. Its own MNA from Fata, Shahabuddin Khan, has also been publicly critical of its attitude.

The PTI, though supports mainstreaming of Fata through merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, has never considered it as a matter of priority or one of its main demands/programmes. The PPP can claim credit for most of the reforms in Fata to date, even if not very fundamental. With the noble exception of its senator Farhatullah Babar, it has been mostly silent during the current push for change.

The smaller parties, like ANP, QWP and some independent groups of activists like Aman Ittehad led by Said Alam Mehsud and the elected parliamentarians from Fata; have been very actively supporting the change in the status of Fata, at the core of that change being its merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

PkMAP and JUI-F have been opposing it strongly. However, it must be noted that the support or opposition from these smaller parties is not making much impact.

It must be realised that if Rewaj Regulations along with extension of Islamabad High Court Jurisdiction kill the whole reform process initiated in 2015, this will mean continuation of special status of Fata with minor reforms. This will be a far cry from the fundamental changes promised in the report of the Fata Reforms Committee in 2016, furthering the crisis of democracy and peace, not just in Fata but all of Pakistan.

If the major political parties make it a matter of priority, they can make it happen. In the process, they can strengthen democratic decision-making and themselves too. Their ability to bring a fundamental change in Fata will strengthen democracy in Pakistan by proving their capability to make serious and fundamental impact on decision-making.