With social media playing the arbiter of taste, there is increased democratisation and it is not just the way that poetry is shared that will be influenced but also how it is done

A hand lifts the Lihaaf (quilt) to reveal an animated visual of a smiling, undeterred Ismat Chughtai fanning herself with a hand fan while sitting in a garden. This is an animation, a gif, that was posted on Khwaab Tanha Collective’s, (a Facebook page that creates animation of poets and their poetry) in memoriam of Chughtai who wrote ‘Lihaaf’, the controversial short story in the 1940s, that landed her in the middle of an obscenity trial.

Scroll down and the next animation is that of poet and lyricist Gulzar who just celebrated his 83rd birthday. The visuals flutter between a sketch of Gulzar and a piece of his poetry written in Urdu, and Hindi script: Aadatan tum nay ker diyay waaday, aadatan hum nay aeitbaar kiya, Hum nay aksar tumhaari raahon may ruk ker apna hi intezaar kiya.

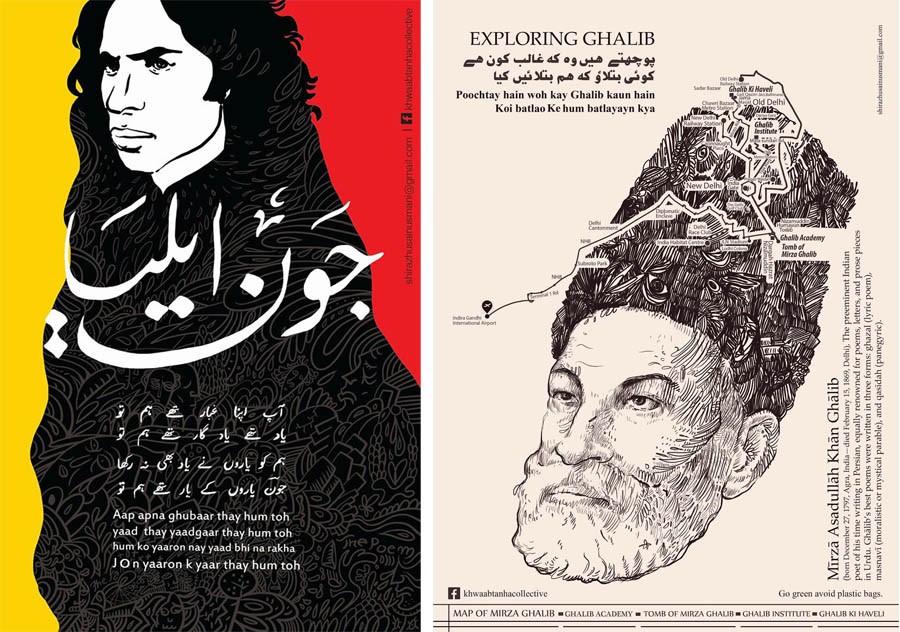

Post after post is a promising combination of graphic design, carefully curated literary text and pop art representations of men and women of letters. Delhi-based artist and literature aficionado Shiraz Husain’s venture, Khwaab Tanha Collective, may roughly translate into a solitary dream but the page has 6,741 followers.

"Boring visual representation of Urdu poetry is what compelled me to start," Shiraz Hussain tells The News on Sunday. "Everyone has their own sea of imagination. I use from mine when I draw but I don’t want to force it on others. A couplet is a painting in itself, which everyone visualises in their own way, so I don’t paint my interpretation of that couplet; instead I draw the poet or writer of that particular piece".

Explaining further why he decided to bring innovation to the way Urdu poetry is shared online, the 31-year-old says that while it is common to have posters of athletes and Hollywood stars on our walls, we hardly celebrate our poets in visual culture and this is where Khwaab Tanha comes in: it engages viewers by filling this visual lacuna. He sketches his subjects in poses that candidly communicate their personalities and attitudes.

What kind of text makes the cut? "That which appeals instinctually", he quips.

Husain is trained in fine arts, and holds a masters and a bachelors degree in Applied Art from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, but has been reading Urdu literature from a very young age.

He was exposed to Urdu literature very early in his life. His grandfather worked with Abdul Haq, popularly known as Baba-e Urdu for his services to the language. Husain’s father, an amateur poet, used to teach Urdu in one of India’s oldest schools, and his sister works in Qaumi Council Bara-e-Farogh-e-Urdu Zubaan. There are times when he consults with his family and senior Urdu writers when creating a post.

Back home in Pakistan, there are other ways of sharing poetry on social media. Nearly a fortnight ago, 23-year old Asra Ahmed conducted a live Facebook session where she recited two of her own ghazals at an online book forum.

"Social media has made people more interested in reading legendary poets like Iqbal, Ghalib, Jaun Elia and the like," she says. She is studying to become a doctor but also wants to publish a book of poetry. She points out that social media has allowed young and new people to come forward and reach out to a large audience. She adds that her father who had his shairi looked at by Jaun Elia himself guides her.

"Poetry was something that was only limited to Urdu books and discussed in homes where parents were fond of the sweetness it left on the tongue," comments Sidra Amin, a 22-year old engineering student who follows Khwaab Tanha Collective.

She says social media posts and pages have reinvigorated interest in Urdu poetry. "But social media has its fair share of disadvantages. Only the kind of poetry that makes sense to people, is easily understandable, or relatable is widely-read and usually more complex poetry gets ignored. Another huge problem is that people misjudge poets like Jaun Elia, Allama Iqbal, and innumerable others, since they are quoted out of context. Many couplets are misattributed and there are few platforms to change the authenticity of that poetry."

"I’m usually enraged by the wrong imla and often even the wrong shair; even spoiling the meters in social media posts whether these are images or regular posts. Not to mention totally wrong shair attributed to poets who had nothing to do with these monstrosities; like using Iqbal or Ghalib image and then writing God knows what and trying to pass it as their work. I feel Urdu script should be used rather than the easy way out and using Roman," says Shane Hussain Naqvi, a 34-year old tech professional who shares Urdu poetry on social media.

Talking about the artwork in these posts, he says that he dislikes the "use of cartoon-like images and drawings that are used with many of Jaun Elia’s couplets". He doesn’t think Jaun Elia would’ve appreciated them.

"If you read ‘Niazmandana’, the preface of his first book Shayad, you would know that he felt that creating an image spoils the written words," he says.

"But these posts are often how most of our young generation gets their first exposure of poetry beyond their school syllabus and the banality of tashreeh studied to score well in exams. Social media is a reality and has affected how we share ideas and revisit poetry," replies Taimur Rehman, a narrator and reciter of poetry who is an avid Gulzar fan and is founder of Urdu Adab UAE, a non-profit aiming to revitalise Urdu. "It is where they get the most power to choose and it is where poetry looks the most attractive to them."

However, Rehman recognises the flipside to social media gaining prominence as a forum for sharing poetry which is that it is "easy for anyone to create an attractive-looking post with a black background and white font and a sketch of a poet," he adds.

Historically, forms such as poetry and poets in general needed some sort of patronage to flourish, and this helped shape the contemporary canon. So commodification of the form in a way led by the power elite did exist in practice as the role of the court was quite significant. Culture was used as a means by the elite to distance themselves from the ‘uninitiated’ but with social media playing the arbiter of taste today, there is increased democratisation and it is not just the way that poetry is shared that will be influenced but also how it is done.

"Everything has been commodified by social media and poetry is no different. We have created a specific demand for certain poets, when none existed [among the social media savvy generation] beforehand, making them ‘trendy’. Jaun Elia, for example," says 28-year old Ali Sajid Imami, a doctor by profession, a member of an online book club that discusses literature.

Online resources and pages such as Rekhta, Hast-o-Neest and Khwaab Tanha Collective draw people in and lead them to works of the greats of yesteryear, people are free to choose from texts of their liking, interpret them as they like and engage in discussion.

Husain has an example to illustrate the role that ventures like his can play, "I was quite young when I saw the iconic prism artwork of the band Pink Floyd , so I was quite amazed at that time and explored the band later that day which eventually leads me to buying my first guitar … what I am doing is introducing the literature giants in pop culture while retaining the aesthetics."

"I remember the protagonist of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, Howard Roark who does not compromise on his artistic perspective and takes on the world. I think this idea was at the back of my mind when I started out. For now, I have Manto and Ghalib diaries, tote bags and posters that I do in addition to these posts," he says.

What would Manto and Ghalib think of the art and innovations that have made their work accessible to society?

"Well they might laugh it off or they might even love it," remarks Husain.