Despite the noble aspirations of the founders of Pakistan and India, both the countries seemed to have decided to come full circle and come back to that moment in history seventy years later

Every year as the anniversary of the independence and partition of British India and the creation of the two dominions of India and Pakistan comes round, a lot of ink is spilled on how we haven’t learnt from the events of that fateful Indian summer, how things remain the same, and how we need to move on.

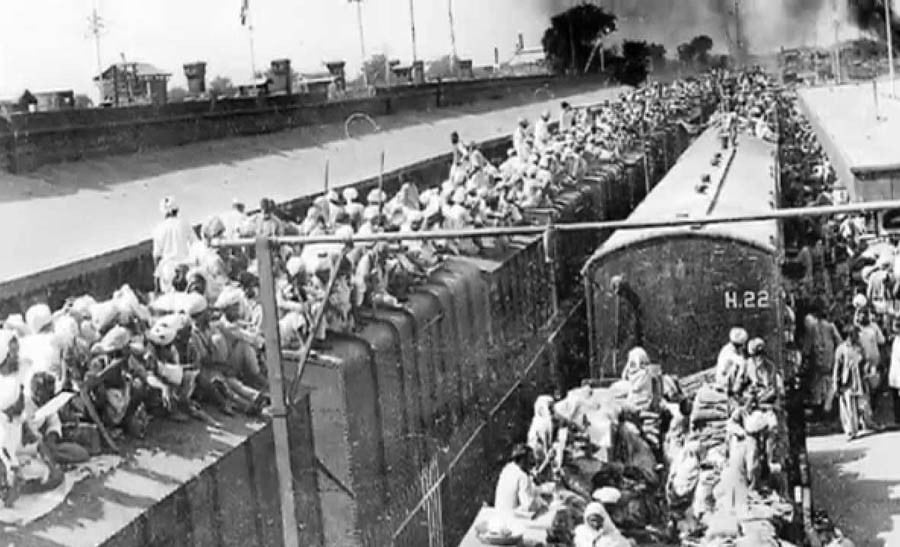

Yet seventy years to the day -- August 15, 1947 -- the second anniversary of the end of the Second World War, we simply seem to have stayed on in the partition moment. It is as if Bishan Singh, that character from Manto’s Toba Tek Singh, still remains on that thin dividing line -- the Radcliffe line, which separates India and Pakistan. Everything seems to have changed and yet we still seem to be placed exactly where we were seventy years ago.

As I reread that famous (or shall I say infamous?) speech of Jinnah on August 11, 1947 to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan -- to that motley of men and women, one third Hindu and two-thirds Muslim, I am struck not by the oft quoted part -- that where Jinnah mentions the neutrality of the state in religion, but am impressed that Jinnah begins his speech -- almost as a dismal counterpart to the energetic speech by Nehru at the stroke of the midnight hour on August 15, by mentioning ‘bribery and corruption’ as the biggest curses which will already ail the still-to-be-formed country. It is as if Jinnah presaged the long list of corruption scandals, the whisperings of Swiss accounts, and even the faint echo of the distant Panama, all those years ago.

Next Jinnah mentions, ‘black-marketing’ as ‘another curse.’ This one struck me even more as imagine the people who were already profiting from the misery of others. We often mention those cold, heartless monsters, who killed scores of people in the holocaust of the partition, but seldom mention those who became rich because of the shortage of food, rations and the like. There was one massacre by the sword and bullet and another by the hoarders who were filling their pockets while their compatriots went hungry and were starving to death. Certainly, as Jinnah said, that black marketing was ‘a greater crime than the biggest and most grievous of crimes.’

Continuing his cold and real speech, Jinnah next mentions the ‘evils’ of ‘nepotism and jobbery.’ The ailing Jinnah knew that his only issue was never going to follow him into politics -- she was happily married in distant Bombay and largely estranged from him, yet perhaps he knew that in time the Bhuttos, the Sharifs will rise in addition to the Mamdots, the Tiwanas, the Haroons and the Khuros.

Keeping it ‘in the family’ was what Jinnah called a ‘legacy’ we had inherited and he most certainly wanted his new country to break from it. His vision -- a bit too idealistic -- was to create a new society based on the high ideals of meritocracy, but he forgot that he was dealing with mere mortals, who instead of looking upon him as a politician and statesman would put him on the high pedestal of ‘RehamatUllah Alai’---little did Jinnah know that he would soon outshine Gandhi in religious motifs, and while Gandhi is eventually mortalised, and hence liable to criticism, he would be immortalised and elevated, though sadly by the men who would rather put up his picture than listen to his words.

Jinnah also spoke of minorities in his speech. He had lived the life of a minority and was fearful of what it would do to him and to his people -- the Muslim nation in India, he was leading. Hence, he implored that the ‘angularities’ of ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ should be done away with in the new state of Pakistan. But the state of Pakistan became so successful in the issue of minorities, that not only did it preserve its existing minorities, it created new minorities. In fact, Pakistan perhaps made a world record when the Bengali majority was turned into a minority. Now even the religious community Jinnah was part of is considered a ‘minority’. So perhaps we are half way there with no real majorities, just lots of minorities who are constantly at war with each other.

When Jinnah spoke that crisp, yet humid, August morning in Karachi, Pakistan was going to be composed of two wings -- East Bengal and Sylhet and West Pakistan, composed of the partitioned West Punjab, Sindh, NWFP and British Balochistan. But within twenty-five years, the eastern part was lost and now strives ahead under the name of Bangladesh. There August 14 or 15 (depending on how you see it), only changes the master, without the ushering in of freedom. Even though Bengal was divided by the same pencil of Sir Cyril Radcliffe as the Punjab, the Bangladeshis prefer to ignore what happened in the summer of 1947. A land which has suffered three partitions, they perhaps have had an overload, and like to mention only the 1971 one which led to their independence.

Today Bangladesh is more stable, more prosperous and more forward looking than the Pakistan it left. So perhaps it’s best that they don’t want to carry the heavy burden of 1947 too.

On the other side of the Punjab Radcliffe line, things are now even more confusing. Taking the new steps from Lahore district to Amritsar district at Wahga, one is simply confused where one is now. From the secular vision of Nehru, India is now fast becoming the vision of Sarvarkar (reconversion of the converted Hindus back to Hindu religion). The Green flag of the Muslim League in Pakistan is now proudly countered by the Saffron emblem of a rising Hindutva in India. In a land where Gandhi was called ‘Bapu’, the organisation his assassin was proudly a member of is in government, and the present prime minister thunders for a ‘Congress Mukt Bharat’, the party that Nehru led till his death. In a land where stalwarts like Dr Zakir Hussain and Dr APJ Abdul Kalam were presidents, not one Muslim was even given a ticket in the recent Uttar Pradesh elections by the ruling BJP. Where under Nehru the country’s diversity made it ‘India’ today its Hindu homogeneity is the hallmark of a new India. A rising, more prosperous India, is now exactly what its founding fathers loathed.

‘Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny’, exclaimed the master orator Nehru as he ushered in independent India at the stroke of the midnight hour. Just like Jinnah who wanted to ‘bury the hatchet,’ Nehru also looked towards the future, to a time of peace, cooperation and brotherhood. Yet despite the noble aspirations of the founders of both countries, both the countries seemed to have decided to come full circle and come back to that moment in history seventy years later.

Gandhi spent the moment of independence not in the grand Durbar Hall in Delhi, not jubilating with the Congress leaders, but with the distressed, marginalised, and oppressed in Bengal. He knew going to Delhi made no sense. He knew that it’s not easy to move on. He new that it would be difficult to dispel the comment of a British civil servant who was rumoured to have exclaimed ‘We found India in a mess, and we are leaving it in a mess’. He knew, but we didn’t. And seventy years down the line we are still trying to figure it out.